Russell - A Very Short Indroduction (16 page)

Russell never had inflated expectations of education. But despite the disillusionment prompted by his practical experiment in schoolteaching, he retained his characteristic liberal belief that it is chiefly on education that hopes for a better world must focus. In his popular writings on social and political questions, Russell was indeed tirelessly attempting to do just that: to educate, with the whole world as his classroom. Despite everything, he never lost hope that vital, brave, sensitive, and intelligent people could be brought into being if only they are given the right kind of guidance in childhood.

Politics

If we are to understand politics, Russell held, we must understand power. All political institutions are historically rooted in authority; at first, the authority of a tribal leader or king, to whom people submitted out of fear; later, to the institution of kingship, to which people gave allegiance as a matter of custom. Russell disagreed with those who held that civil society arose from an original ‘social contract’ in which individuals gave up part of their freedom in return for the benefits – not least among them security – of social living. If there were any original contract, he said, it was one between members of the ruling élite, a ‘contract among conquerors’, to which they subscribed in order to consolidate their position and privileges (

Power

, 190).

In Russell’s view, history suggests that monarchy constitutes the earliest type of developed political arrangement. Authority filtered down through the social hierarchy, from the king – who, in many dispensations, claimed to receive it from God – to the nobility, the gentry, and so on down to the humblest man at the head of his own family in his cottage. The advantages of the system, when it commanded the loyalty of those involved, was social cohesion. Its disadvantage is that the absolute ruler has no incentive to rule benevolently; there are many examples of such arrangements becoming tyrannical and cruel (

Power

, 189).

The natural successor to monarchy is oligarchy, Russell says, and this admits of a variety of forms: aristocracy, plutocracy, priesthoods, or political parties. Rule by the rich, as exemplified in the free cities of the Middle Ages and by Venice until Napoleon captured it, seemed to Russell to have worked rather well, but he did not think modern industrialists were up to the same mark (

Power

, 193). As with monarchy when it commands loyalty, both Church and party political oligarchies can generate social cohesion through the sharing of beliefs or ideology, but the great danger they pose is their threat to liberty. Such oligarchies cannot tolerate those who disagree with their views, nor can they permit the existence of institutions which might challenge their monopoly of power (

Power

, 195–6).

Nevertheless, Russell noted, there is a benefit to be had from oligarchic forms of government, provided that liberty can be secured under them, which is that they allow for the existence of a leisured class. The reason is that leisure is a condition for the flourishing of mental life – for literature, learning, and art. In the past this involved the sacrifice of the many, who had to toil long hours so that the few could enjoy the requisite freedoms. But if good use is made of modern technology, Russell believed, ‘we could, within twenty years, abolish all abject poverty, quite half the illness in the world, the whole economic slavery which binds down nine-tenths of our population: we could fill the world with beauty and joy, and secure the reign of universal peace’ (

Political Ideals

, 27). Russell made these utopian remarks in 1917, by way of lighting a candle in the darkness of war, but they are not entirely devoid of point: given the success of science and its intelligent use for peaceful purposes, there is no reason why more leisure, and therefore more of the conditions for creative and flourishing life, should not be possible for more people. Such a possibility undermines the argument for social structures which support a leisured class, and makes instead a strong claim of justice in favour of democracy.

Still, the difference between democracy and oligarchy is only a matter of degree, Russell observes, because even under democracy only a few people can hold real power. This made Russell cynical even about the vaunted British parliamentary model, in which the average Member of Parliament is in reality little more than voting fodder for his or her party. But the picture is not wholly bleak as regards democracy, for although it cannot guarantee good government, it can nevertheless prevent certain evils, chiefly by ensuring that no bad government can stay in power permanently (

Power

, 286).

The best thing about democracy for Russell is its association with ‘the doctrine of personal liberty’, which he valued highly. The doctrine consists of two aspects. The first is that one’s liberty is protected by requirements of due process at law, which shields one from arbitrary arrest and punishment. The second is that there are areas of individual action which are independent of control by the authorities, including freedom of speech and religious belief. These freedoms are not without limits; in wartime, for example, it might be necessary to curb free speech in the interests of national security. Russell recognized that there can indeed be much tension between the interests of society as a whole and those of an individual who desires maximum freedom. ‘It is not difficult for a government to concede freedom of thought when it can rely upon loyalty in action,’ he remarked, ‘but when it cannot, the matter is more difficult’ (

Power

, 155).

For Russell, questions of political organization are crucially questions of economic organization. The early, pre-First World War, Russell was a champion of free trade, and he remained a supporter of free enterprise for the good reason that he was opposed to the over-accumulation of economic power in any one set of hands, whether of capitalists or governments. He saw no reason why people should not be wealthy if they had earned it but was hostile to the idea of inherited wealth. Although he allied himself for most of his adult life with socialism, it was in a particularly qualified way. The role of government in economic affairs, he said, is to guard against economic injustices. But this is not best done by vesting ownership or control of the means of production in government hands, as in the Communist experiment of the Soviet countries. Rather, Russell was attracted by what in France is called Syndicalism and in England Guild Socialism, the theory that factories should be managed by their own workers, and that industries should be organized into Guilds. These would pay a tax to the state in return for their raw materials, and otherwise would be free to arrange wages and working conditions and to sell their products. Further, the Guilds would between them elect a Congress, consumers of their products would elect a Parliament, and the two together would be the national sovereign body, determining taxes and acting as the highest court in the land to decide the interests of workers and consumers alike (

Roads

to

Freedom

, 91–2). To ensure that the existence of Guilds does not compromise freedom, especially of expression, Russell proposed that a small minimum wage should be paid to everyone irrespective of whether or not he works, so that each could be quite independent if he chose. Anyone who wished to have more than this minimum would work, and the more they worked the richer they could be. He shrugged off the obvious objection that the scheme would be impossible if people chose not to work, thus producing no tax revenue but still requiring their minimum wage, by saying that most of them would be drawn to work by the inducement of prosperity; and anyway conditions of work and life generally would be pleasant under Guild Socialism, so they will not mind doing it (ibid. 119–20).

The principle at issue in Guild Socialism is devolution of that key political commodity,

power

. In Russell’s view, concentration of power, especially in government hands, increases the likelihood of war. Its dissipation among many groups and individuals is therefore highly desirable. ‘The positive purposes of the State, over and above the preservation of order, ought as far as possible to be carried out, not by the State itself, but by independent organisations which should be left completely free so long as they satisfied the State that they were not falling below a necessary minimum’ (

Principles of Social Reconstruction

, 75). Russell formulated this view relatively early in his political thinking, and kept faith with it thereafter. In

Power

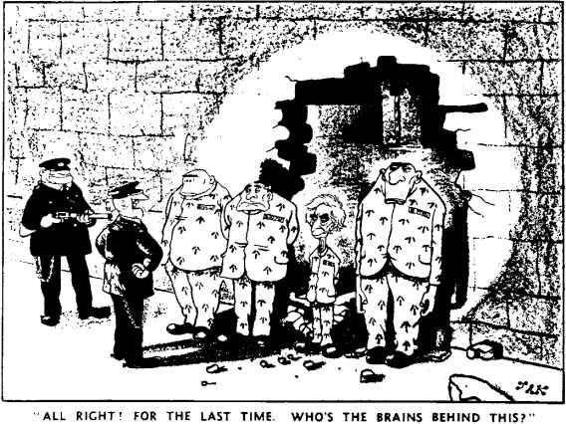

he argued that there is more need than ever for safeguards against official tyranny, propaganda, and the police – in connection with whom he made the original suggestion that there should be, in effect, custodians of the custodians: one police force should carry out the normal business of gathering evidence necessary for arresting supposed criminals and putting them on trial, while the other should be devoted to gathering evidence to prove those same people innocent.

Allied to the decentralizing thrust of Russell’s politics was his hostility to nationalism. Before the Second World War he attacked it as ‘a stupid idea’ and ‘the most dangerous vice of our time’, which threatened the destruction of Europe. After the Second World War he saw it repeating itself in the Soviet Union and America, only this time – because both possessed weapons of mass destruction – it was vastly more dangerous. The only sure antidote to nationalism and the threat it poses, he argued, is World Government.

On the face of it this belief hardly seems consistent with Russell’s decentralizing beliefs, and he recognized the risk of placing military might in the hands of a single universal power. But he thought it infinitely preferable to more world wars, in which weapons of ever greater destructive capability would be used, with the likelihood of destroying life on earth. This seemed to Russell so great an evil that practically anything would be preferable. But a world government need not be merely a lesser of evils. A good way of maintaining a measure of control over it would be to devolve as much power, in all but military respects, to the smallest local units feasible. Nevertheless, said Russell, in the end:

[a] world-State or federation of States, if it is to be successful, will have to decide questions, not by the legal maxims which would he applied by the Hague tribunal, but as far as possible in the same sense in which they would be decided by war. The function of authority should be to render the appeal to force unnecessary, not to give decisions contrary to those which would be reached by force.

(

Principles

of

Social Reconstruction

, 66)

How might a world government be brought into being? National governments are unlikely to wish to surrender their sovereignty for so utopian a vision. On Russell’s view, the most likely method is that one power or power bloc will eventually gain control of the world, and de facto will constitute the world government. In Cold War terms, Nato and the Warsaw Pact – or more accurately, their respective principals – could be seen as vying to achieve this outcome. Russell likened it to the development of orderly government in medieval times: a king seizes power, and then, by a process of evolution, sovereignty is brought under more and more democratic control. He thought that such a process might happen in the case of world government. The ‘substitution of order for anarchy in international relations, if it comes about, will come about through the superior power of some one nation or group of nations. And only after such a single Government has been constituted will it be possible for the evolution towards a democratic form of international Government to begin’. He thought this might take a hundred years, during which the international government would have begun to earn ‘the degree of respect that will make it possible to base its power upon law and sentiment rather than upon force’ (

New Hopes For A Changing World

, 77–8).

A theme in all Russell’s thinking about politics and government is the problem of balancing individual freedom and the need for international peace. But in the end the contest between them is an unequal one. There is not only no such freedom, but not even the possibility of such freedom, if mankind is destroyed by war. Accordingly Russell was prepared to see freedom compromised or delayed in the interests of saving humanity. Naturally he wished that peace and freedom could be secured together; but his experience of men had obliged him to accept that greed, brutality, irrationality, and other common human characteristics make this unlikely. This thought, he wrote, often drowned him in despair. It had done so during the First World War, as hundreds of thousands of men were driven to useless mutual slaughter in the mud of Europe. How much more did it do so after the Second World War, when the potential victims of nuclear weapons are no longer just armies, or even nations, but – at a possible worst – the entire population of the world. From one point of view it is extraordinary how few had the clarity to see this fact and the imagination to feel its horror. It is greatly to Russell’s credit that he did both.

War and peace

Russell opposed the Boer War and the First World War, supported the Allied effort in the Second World War, and laboured mightily against the imminent possibility of a Third World War and the actuality of the