Russell - A Very Short Indroduction (17 page)

11.

This cartoon from the

Evening Standard

refers to the week-long prison sentence served to Russell in September 1961, following his conviction on public order charges brought after a large central London peace demonstration in commemoration of Hiroshima.

Vietnam War. He made war on war until his death at the age of 97. Both his early and his late anti-war activities were greeted with hostility and landed him in prison. Yet no one can now say he was wrong to take the stands he did; when the jingoism and flag-waving stops, and the awful costs are counted against a soberer assessment of the reasons why they were paid at all, people begin to see war in retrospect as Russell had the genius to see it at the time.

Russell never changed his view that the First World War was unnecessary. There was nothing really at issue between Germany and Britain in 1914 except national pride and some resolvable irritation over imperial questions. He thought that hostilities could have been avoided by negotiation, which would have soothed Germany’s justifiable annoyance that it had not fared as well in the colonial race as it might have done. But the Foreign Ministries of Europe were staffed by aristocrats motivated more by considerations of

amour propre

than common sense.

Russell’s opponents in the First World War argued that Germany was guilty of aggression and expansionism, and sought hegemony in Europe, which threatened Britain’s liberty because, if Germany won, it would stamp its authoritarian and bureaucratic imprint over everything. Therefore Britain had an excellent motive to fight. Russell did not accept either the imputed motive or the likely outcome if Britain refused to fight; he thought it would most likely have been a rerun of the FrancoPrussian conflict of 1871, short and decisive. But even if the Kaiser won – which would be an evil, but not so great an evil as the war itself – the chief point for him was that to go to war one must have an overwhelmingly good reason to do so, and no such thing existed in 1914.

In 1939, matters were very different. During the 1930s Russell was in fact an appeaser, as his

Which Way To Peace?

of 1936 testifies. He would not let this book be reprinted, however, because by the time he finished it he had come to feel that it was insincere, and that the circumstances of the 1930s were too different from those of 1914:

I had been able to view with reluctant acquiescence the possibility of the supremacy of the Kaiser’s Germany. I thought that, although this would be an evil, it would not be so great an evil as a world war and its aftermath. But Hitler’s Germany was a different matter. I found the Nazis utterly revolting – cruel, bigoted, and stupid. Morally and intellectually they were alike odious to me.

(

A

430)

He found the thought of defeat by such people ‘unbearable, and at last consciously and definitely decided that I must support what was necessary for victory in the Second World War, however difficult victory might be to achieve, and however painful its consequences’ (ibid.).

The terrifying end to the war in the Pacific, with the dropping of atom bombs on Japanese cities, instantly alerted Russell to the fact that something quite new had entered the calculation. In a speech to the House of Lords in November 1945 he warned his peers of the dangers. At first he thought America should use its superiority in atomic weapons to coerce the Russians into not developing them. This has been interpreted as a demand by Russell that the United States should make a preemptive atom bomb attack on Russia; but he did not go so far. He saw that a window of opportunity existed for the United States to institute world government by means of its military superiority, and he urged it to do so. Although he thought there was a good deal wrong with America, he much preferred its generally liberal and democratic outlook to the tyranny in the Soviet Union. Indeed in the years after the Second World War Russell’s hostility to the Soviet Union, already considerable as a result of his visit in the early 1920s, increased. It is a measure of his disgust at the Vietnam War just 15 years later that he came to denounce the Americans in the same ferocious terms. The change of heart was not, however, sudden. Macarthyism in the United States, and its bellicose Macarthyite anti-Communist foreign policy abroad, gradually led him to think that the Americans were a greater threat to peace than the Soviet Union. The Cuban missile crisis of 1961 confirmed him in this view. Thereafter he was determinedly anti-American.

What altered matters for Russell on the atomic weapons question was, first, Soviet acquisition of the bomb in 1949, and then, in 1954, Britain’s test explosion on Bikini Atoll. In response to the latter he made a famous Christmas radio broadcast, ‘Man’s Peril’, warning Britain and the world of the horrendous dangers to which everyone was now exposed. This broadcast was a turning point; from it dated the true beginning of campaigns against the existence of weapons of mass destruction. He was inundated with letters. Using the momentum generated by his broadcast, he organized an international petition signed by leading scientists. He never stopped demanding that Britain should scrap its nuclear weapons, one of the reasons for doing which, he argued, is to give a moral lead to other nations to do the same.

His views on how the danger now faced by the world should be managed changed during the 1950s as the international situation worsened and his own endeavours met with failure. He wrote and broadcast; in addition to his petition he organized a conference bringing together scientists from both sides of the Iron Curtain; and he participated in the setting up of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and served as its first President. As these peaceful and reasoned means ran repeatedly into the brick wall of government intransigence, he became more despairing. He resigned from CND, therefore, and joined the much more militant Committee of 100, which began a campaign of civil disobedience. The campaign earned him a second prison sentence, 42 years after the first. In all this there was little scope for theorizing, because Russell felt there was no time for it; what was needed was action.

In his very last years Russell’s attention was absorbed by the Vietnam War. By now surrounded by others who made use of his name on publications and press releases which – as their grammar as well as their tone suggests – could not have emanated from him personally, he attacked the United States and, in particular, its military-industrial complex and the CIA, charging them with aggression in Vietnam and the perpetration of war crimes. With Jean-Paul Sartre and others he sponsored the International War Crimes Tribunal, aimed at putting America on trial for its activities in Vietnam. At the time people thought that the Tribunal’s charges against the United States were merely hysterical. With the subsequent publication of US government files, many of the charges are now known to be true.

In at least one respect there is a remarkable consistency between Russell’s opposition to the First World War and his opposition to the Vietnam War. It is that in both he thought there was no question of a genuine good at stake, and that both were prompted by the lowest instincts in man – the brutal, mindless, aggressive instincts, which, once they are in control, license anything: the bombing of women and children, the use of poison chemicals, the smokescreen of propaganda and lies directed at the home population. At the end of his very long life Russell must have found it appalling that between 1914 and 1970 weapons of war had grown more destructive than ever, but that mankind had not altered one jot.

Chapter 5 Russell’s influence

If you wish to see Russell’s monument, look around you at mainstream philosophy in the English language as it has been practised since the years between the two world wars. Look also at logic, at the philosophy of mathematics, at the changed moral climate of the twentieth-century Western world, and at attempts to halt the proliferation of nuclear weapons. The complete history of any of these matters must refer to Russell.

In some of these respects he is just one actor among others; he was far from alone, for example, in bringing about the century’s revolution in morals. He was much closer to centre stage in the nuclear disarmament campaign, as he had been in the pacifist movement of the First World War.

But in philosophy his place is so pivotal that, as remarked in the opening chapter, he is practically its wallpaper. His philosophical inheritors carry on their philosophical work in his style, addressing problems he identified or to which he gave contemporary shape, using tools and techniques he developed, and all in large agreement with the aims and assumptions he adopted. A measure of the extraordinary pervasiveness of his influence is that many among the younger generations of twentieth-century philosophers are barely conscious that all this is owed to him.

Contemporary philosophy, said Jules Vuillemin, began with Russell’s

The Principles of Mathematics

. The celebrated American philosopher W. V. Quine, quoting this remark, varies the metaphor: for him this work is ‘the embryo of twentieth-century philosophy’ (W. V. Quine, ‘Remarks for a Memorial Symposium’, in Pears,

Bertrand Russell

, 5). Quine was himself attracted to philosophy by reading Russell. As a young man his first education in logic, science, and philosophy was provided by Russell’s books; like many others he felt their ‘drawing power’, and was lured by them first into the study of logic and the philosophy of mathematics, and then into the theory of knowledge and philosophy of science. ‘The authentic scientific ring of Russell’s logic echoed in his epistemology of natural knowledge,’ Quine wrote. ‘The echo was especially clear in 1914, in

Our Knowledge of the External World

. That book fired some of us, and surely Carnap for one, with new hopes for phenomenalism’ (ibid. 2–3). To that book Quine adds the lectures on Logical Atomism and both

The Analysis of Mind

and

The Analysis of Matter

as seminal works; ‘there is no missing [their] relevance to the Western scientific philosophy of the century’ (ibid.). And there is no missing the relevance to Russell’s philosophy, in turn, of his logic – ‘Russell’s name is inseparable from mathematical logic, which owes him much’ – especially the Theory of Descriptions and the Theory of Types.

Russell invented Type Theory to overcome the paradoxes he had discovered while trying to place mathematics on logical foundations. During his efforts to solve this problem he canvassed a number of alternatives, including one which, ironically, was later to carry the day in set theory – in a version worked out by Ernst Zermelo – thus displacing the theory Russell eventually devised. But his theory of types was immensely influential in philosophy nevertheless. Its motivating idea was adapted by the Logical Positivists of the 1920s and 1930s in mounting their attack on metaphysics, and Gilbert Ryle applied a different version of it to the elimination of ‘category mistakes’, the kind of mistake exemplified by someone’s thinking that the University of Oxford is an entity additional to all the colleges and institutions comprising it. In Quine’s view the theory of types also influenced Edmund Husserl and, along with other aspects of Russell’s logic, the great Polish logicians Stanislaw Lesniewski and Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz (Pears,

Russell

, 4).

To this must be added the importance of the Theory of Descriptions. Quine states:

Russell’s logical theory of descriptions was philosophically important both for its direct bearing on philosophical issues having to do with meaning and reference, and for its illustrative value as a paradigm of philosophical analysis. Russell’s theory of logical types established new trends at once in the metaphysics of ontological categories, in the antimetaphysics of logical positivism, and, overspilling philosophy at the far edge, in structural linguistics. Is it any wonder that Vuillemin sees Russell’s work in logic as inaugurating contemporary philosophy’?

(Pears,

Russell

, 4–5)

When Russell died Gilbert Ryle gave an obituary address to the Aristotelian Society, the chief British philosophical club, to which Russell, beginning in 1896, had often read papers. In it Ryle identified the respects in which, in his view, Russell’s work had given twentiethcentury philosophy ‘its whole trajectory’ (‘Bertrand Russell: 1872–1970’, reprinted in Roberts,

Bertrand Russell Memorial Volume

). One was ‘a new style of philosophical work that Russell, I think virtually single-handedly, brought into the tactics of philosophical thinking’ (ibid. 16). This was the use of difficult cases to test philosophical theses, a form of conceptual experimentation aimed at subjecting the claims and concepts of philosophy to scrutiny. For example, in his paper ‘Mathematical Logic as based on the Theory of Types’ Russell lists seven contradictions demanding solution by a competent theory, and offers it as a test of adequacy for his theory of types that it succeeds in dealing with them all. This technique is now a commonplace of philosophical method. ‘Thought experiments’ are devised to put a view through its

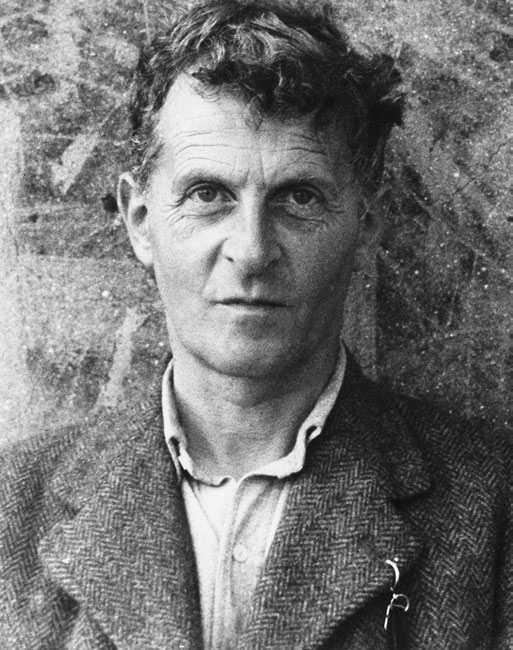

12.

12.

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), Russell’s pupil while in Cambridge before the war.

paces – as in ethics, for example, where a principle is applied to a variety