Sacre Bleu (29 page)

“Thank you, Theo,” Lucien said. “Your opinion means a lot to me, which is why we’ve brought the painting to you unfinished. I’m thinking of painting a scarf—”

“Do you have all of Vincent’s paintings here now?” interrupted Henri.

Theo looked startled at the mention of his brother. “Yes, I have them all here in Paris, although not hanging, obviously.”

“In the lot of his last paintings, were there any figure paintings? Any paintings of women?”

“Yes, one of Madame Gachet; three, I think, of the young girl whose family owns the inn at Auvers, where Vincent was living; and one of the innkeeper’s wife. Why?”

“Often, when an artist is tormented, a woman is involved.”

Surprisingly, Theo van Gogh smiled at this. “Not just artists, Henri. No, when Vincent first went to Arles he mentioned a woman briefly in one of his letters, but it was the way you talk about a pretty girl you see walking in the park, wistful, I think you would call it. Not as if he knew her. Mostly he wrote about painting. You know him—knew him. Painting is all he talked about.”

“Was there something about his painting that would have—that was causing him distress?”

“Enough distress to kill himself, you mean?” Now Theo lost his semblance of gentlemanly detachment and gasped as if unable to catch his breath.

“I’m sorry,” Lucien said, steadying Theo with a hand on his back.

In a second van Gogh snapped back into his clerk aspect, as if they were talking about the provenance of a painting, not the death of his brother.

“He kept saying, ‘Don’t let anyone see

her,

don’t let anyone near

her.’

He was talking about a painting he sent from Arles, but I received no figure painting from Arles.”

“And you don’t know who

‘she’

was?”

“No. I don’t. Perhaps Gauguin knows; he was there when Vincent had his breakdown in Arles. But if there was a woman, he never mentioned her.”

“So it wasn’t a woman…” Henri seemed perplexed.

“I don’t know why my brother killed himself. No one even knows where he got the pistol.”

“He didn’t own a gun?” asked Henri.

“No, and neither did Dr. Gachet. The innkeeper only had a shotgun for hunting.”

“You were a good brother to him,” said Lucien, his hand still on Theo’s back. “The best anyone could expect.”

“Thank you, Lucien.” Van Gogh snapped a handkerchief from his breast pocket and ran it quickly under his eyes. “I’m sorry. I’m still not recovered, obviously. I will find a place for your picture, Lucien. Give me some time to put some of the prints in storage and sell a few paintings.”

“No, that’s not necessary,” said Lucien. “I need to work on her. I meant to ask you, as an expert, do you think I should paint a scarf tied around her neck? I was thinking in ultramarine, to draw the eye.”

“Her eyes draw the eye, Lucien. You don’t need a scarf. I wouldn’t presume to tell you how to paint, but this picture looks finished to me.”

“Thank you,” said Lucien. “That helps. I would still like to work on the texture of the throw she is lying on.”

“You will bring it back, then? Please. It really is a magnificent picture.”

“I will. Thank you, Theo.”

Lucien nodded to Henri, signaling him to pick up his end of the painting.

“Wait,” said Henri. “Theo, have you ever heard of the Colorman?”

“You mean Père Tanguy? Of course. I have always bought Vincent’s paints from him or Monsieur Mullard.”

“No, not Tanguy or Mullard, another man. Vincent may have mentioned him.”

“No, Henri, I’m sorry. I know only of Monsieur Mullard and Père Tanguy in Pigalle. Oh, and Sennelier by the École des Beaux-Arts, of course, but I’ve had no dealings with him. There must be half a dozen in the Latin Quarter to serve the students, as well.”

“Ah, yes, thank you. Be well, my friend.” Henri shook his hand.

Theo held the door for them, glad that they were going. He liked Toulouse-Lautrec, and Vincent had liked him, and Lucien Lessard was a good fellow, always kind, and, it seemed, was turning into quite a fine painter. He didn’t like lying to them, but his first loyalty must always be to Vincent.

“T

HE PAINTING IS NOT SHIT,” SAID

L

UCIEN.

“I know,” said Henri. “That was just part of the subterfuge. I am of royal lineage; subterfuge is one of the many talents we carry in our blood, along with guile and hemophilia.”

“So you don’t think the painting is shit?”

“No. It is superb.”

“I need to find her, Henri.”

“Oh for fuck’s sake, Lucien, she nearly killed you.”

“Would that have stopped you, when we first sent you away from Carmen?”

“Lucien, I need to talk to you about that. Let’s go to Le Mirliton. Sit. Have a drink.”

“What about the painting?”

“We’ll take the painting. Bruant will love it.”

F

ROM INSIDE A RECESSED DOORWAY AT THE REAR OF

S

ACRÉ

-C

OEUR, SHE

watched them walk her picture out the door of the gallery. They moved like a pair of synchronized drunkards, up the middle of the street, sideways, trying to keep the edge of the painting pointed into the breeze. Once they rounded the first corner she quickstepped down the stairs, across the small square, and into Theo van Gogh’s gallery.

“Mon Dieu!”

she exclaimed. “Who is this painter?”

Theo van Gogh looked up from his desk at the beautiful, fair-skinned brunette in the periwinkle dress who appeared to be climaxing on his gallery floor. Although he was sure he hadn’t seen her before, she looked strangely familiar.

“Those were painted by my brother,” Theo said.

“He’s brilliant! Do you have any more of his work I could see?”

TAHRD

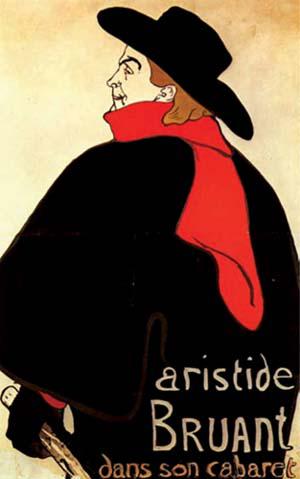

“He was two parts talent, three parts affectation, and five parts noise.”

Aristide Bruant

(poster)—Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, 1892

O

H LOOK, IT IS THE GREAT PAINTER

T

OULOUSE

-L

AUTREC ACCOMPANIED

by some dog-shit unknown bastard!” cried Aristide Bruant as they entered the half-lit cabaret. He was a stout, stern-faced man, in a grand, broad-brimmed hat, high-heeled sewer-cleaner boots, a black cape, and a brilliant red scarf. He was two parts talent, three parts affectation, and five parts noise. Le Mirliton was his cabaret, and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec was his favorite painter, which is why Henri and Lucien were dragging the blue nude into the bar in the middle of the day.

“When you break a tooth on the gravel in your blackberry tart,” Lucien called back, “it will be a present from that same dog-shit unknown bastard!”

“Oh ho!” shouted Bruant, as if speaking to a full house of revelers instead of the four drunken butchers falling asleep over their beers in the dinge of the corner and a bored barmaid. “It appears that I have failed to recognize Lucien Lessard, the dog-shit baker and sometime dog-shit painter.”

Bruant wasn’t being particularly unkind to Lucien. Everything at Le Mirliton was served with a side order of abuse. It was Bruant’s claim to fame. Businessmen and barristers came from all the best neighborhoods of Paris to sit on the rough benches, rub elbows on greasy tables with the working poor, and be outwardly blamed for society’s ills by the anarchist champion and balladeer of the downtrodden, Aristide Bruant. It was all the rage.

Bruant strode across the open floor of the cabaret, snatching up his guitar, which had been resting on a table, as he went.

Lucien set down his end of the painting, faced Bruant, and said, “Strum one chord on that thing, you bellowing cow, and I will beat you to death with it and dismember your corpse with the strings.” Lucien Lessard may have been tutored by some of the greatest painters in France, but he hadn’t ignored the lessons from the butte’s finest crafter of threats, either.

Bruant grinned, held the guitar up by his face, and mimed strumming. “I’m taking requests…”

Lucien grinned back. “Two beers with silence.”

“Very good,” said Bruant. Without missing a step, he turned as if choreographed, docked the guitar on an empty table, and headed back to the bar.

Two minutes later Bruant was sitting with them at a booth, and the three of them were looking at the blue nude, which was propped up against a nearby table.

“Let me hang it,” said Bruant. “A lot of important people will see it in here, Lucien. I’ll put her up high, over the bar, so no one will get any ideas about touching her. They might not buy it, because their wives won’t let it in the house, but they’ll see it and they’ll know your name.”

“You have to show the painting, Lucien,” Henri said to Lucien. “We can put together a show later—maybe Theo van Gogh will sponsor it, but that will take time. I can’t organize it. I need to go to Brussels, and to show with the Twenty Group, and I have promised to print new posters for the Chat Noir and the Moulin Rouge.”

“And he owes me a cartoon for

Le Mirliton,

” said Bruant. He irregularly published an arts magazine with the same name as his cabaret, and all of Montmartre’s young artists and writers contributed to it.

“All right, then,” said Lucien. “But I don’t know what to ask for it.”

“It shouldn’t be for sale,” said Henri.

“I would agree,” said Bruant. “That’s the power of the coquette, isn’t it? Make them want it, but don’t let them have it. Just tease.”

“But I need a sale.” And therein lay the artist’s dilemma: to paint for filthy lucre was a compromise of principles, but to be an artist who didn’t sell was to be anonymous as an artist.

“If she’ll sell now, she’ll sell later,” said Henri. “The bakery makes enough money for you to live.”

“Fine, fine,” Lucien said, throwing his hands up. “Hang her. But if someone makes an offer, I want to know about it.”

“Excellent,” said Bruant, hopping up from his seat. “I’ll go borrow a ladder. You can supervise the hanging.”

When the singer had gone, Henri lit a cheroot with a wooden match and leaned into the cloud of smoke he’d just expelled over the table.

“Before he returns, Lucien, I need to tell you something—warn you.”