Sacre Bleu (51 page)

“And now, puppet, since you have someone to look after you, I am going home.”

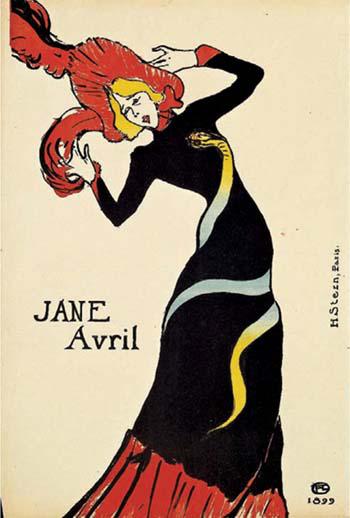

Jane Avril

(poster)—Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, 1893

T

WO MEN IN BROAD-BRIMMED HATS, ONE TALL, ONE OF AVERAGE HEIGHT,

stood at the taxi stand at the east end of the Cimetière du Montparnasse, looking toward the entrance to the Catacombs across the square. One carried a black ship’s signal lantern with a Fresnel lens, which he held by his side as if no one would notice; the taller one had a long canvas quiver slung over his shoulder, from which protruded the wooden legs of an artist’s easel. Both wore long coats. Other than the lantern, they were conspicuous only in that they were standing at a taxi stand, at midday, with no intention of taking a taxi, and the shoes of the taller man were smoldering.

“Hey, your shoes are smoking,” said the cabbie, who leaned against his hack, chewing an unlit cheroot and scowling. He had already asked them three times if they needed a taxi. They didn’t. They were both peeping out from under the brims of their hats, surreptitiously checking on the progress of a little man in a bowler hat who was leading a donkey across the square.

“It is no concern of yours, monsieur,” said the tall man.

“I think he’s going into the Catacombs,” said the shorter one. “This may be it, Henri.”

“Are you two detectives?” asked the cabbie. “Because if you are, you are horrible at it. You should read this Englishman Arthur Conan Doyle to see how it is done. The new one is called

The Sign of the Four.

His Sherlock Holmes is very clever. Not like you two.”

“The Catacombs?” Henri pulled his pant legs up so that the cuffs hovered above his shoes, showing his gleaming brass ankles. “I’m finally tall and I have to go into the Catacombs, where it will be a disadvantage.”

“Perhaps the Professeur can design a new model powered by irony,” said Lucien, tilting his head so the brim of his hat lifted to reveal his grin. The Loco-ambulators had allowed them to follow the Colorman at a distance for over a week, without revealing Henri’s conspicuous height or limp, but now it seemed the steam stilts were going to become a distinct disadvantage.

“We have a little time.” Lucien set the lantern down and crouched by Henri’s feet. “We need to let him get ahead of us if we’re going to follow him down there. You there, cabbie, help me get his trousers off.”

“Messieurs, this is the wrong neighborhood and the wrong time of day for such a request.”

“Tell him you’re a count, Henri,” said Lucien. “That usually works.”

Five minutes later Toulouse-Lautrec, with his trousers rolled up and his long coat dragging the ground, led the way across the square. They’d given the cabbie five

francs

to watch the Loco-ambulators and showed him the double-barreled shotgun in the canvas quiver, borrowed from Henri’s uncle, to let him know what would happen to him should he decide to abscond with the steam stilts. He, in turn, charged them two

francs

for a guaranteed—more or less—complete map of underground Paris.

Toulouse-Lautrec unfolded the map until he had revealed the seventh level below the city, then looked to Lucien. “It follows the streets as if on the surface.”

“Yes, but with fewer cafés, more corpses, and it’s dark, of course.”

“Oh, well then, we’ll just pretend we’re visiting London.”

The city of Paris had installed gaslights for the first few hundred yards of the Catacombs, as well as a man at the entrance who charged twenty-five

centimes

for the pleasure of looking at the city’s bones.

“That shit is morbid, you know that, no?” said the gatekeeper.

“You’re the gatekeeper of an ossuary,” said Lucien. “You know that, yes?”

“Yes, but I don’t go down there.”

“Give me my change,” said the baker.

“If you see a man with a donkey, tell him I turn the gaslights off at dark and he’ll have to find his own way out. And report to me if he’s doing anything unsavory down there. He goes down there and stays for hours at a time. It’s macabre.”

“You know you charge people money to look at human remains, no?” said Lucien.

“Are you going in or not?”

They went down the marble steps into wide tunnels lined with stacked tibiae, fibulae, femurs, ulnae, radii, and skulls. When they reached the iron gate with the sign that said

NO VISITORS BEYOND THIS POINT,

Lucien knelt down to light the signal lantern.

“We’re going in there?” asked Henri, staring past the bars to infinite black.

“Yes,” said Lucien.

Henri held the cabbie’s map up to the last gas lamp. “Some of these chambers are massive. Surely the Colorman will see our lantern. If he knows he’s being followed, he’ll never lead us to the paintings.”

“That’s why the signal lantern. We close it down until we can only just see beyond our feet, so we don’t trip. Keep it directed downward.” Lucien held a match to the wick, then, once it was going, adjusted the flame until it was barely visible.

“And how will we know which way he goes?”

“I don’t know, Henri. We’ll look for his lantern. We’ll listen for the donkey. Why would I know?”

“You’re the expert. The Rat Catcher.”

“I am not the expert. I was seven. I went into the mine only far enough to set my traps, that was all.”

“Yet you discovered Berthe Morisot naked and painted blue. If not an expert, you have extraordinary luck.”

Lucien picked up the lantern and pushed open the gate. “We should probably stop talking. Sound carries a long way down here.”

The arch that contained the iron gate was smaller than the rest of the vault and Lucien had to duck to go through. Henri walked straight through, until the easel he carried on his back caught the archway and nearly knocked him off his feet.

“Perhaps we should leave the easel here, just bring the shotgun.”

“Good idea,” said Henri. He pulled the shotgun from the canvas sleeve, then set the bag and the easel to the side of the gate in the dark.

“Breech broken,” said Lucien, thinking that the next time Henri tripped, the gun might discharge, taking off one of their heads or some other appendage to which they might have a personal attachment.

Henri broke the shotgun’s breech and dropped in two shells he’d had in his pocket, then paused.

Lucien played the hairline beam of light up and down his friend’s face. “What?”

“We are going into these tunnels to kill a man.”

Lucien had tried not to think of the specific act. He’d tried to keep the violence abstract, an idea, or better yet, an act based upon an ideal, the way his father had helped him through dispatching the rats when he was a boy and he’d find a suffering rodent still alive, squirming in the trap. “It is mercy, Lucien. It is to save the people of Paris from starvation, Lucien. It’s to preserve France from the tyranny of the Prussians, Lucien.” And one time, when Père Lessard had drunk an extra glass of wine with lunch, “It’s a fucking rat, Lucien. It’s disgusting and we’re going to make it delicious. Now smack it with the mallet, we have pies to make.”

Lucien said, “He killed Vincent, he killed Manet, he’s keeping Juliette as a slave: he’s a fucking rat, Henri. He’s disgusting and we’re going to make him delicious.”

“What?”

“Shhhhh. Look there, it’s a light.”

After only a minute out of the gaslights their eyes had adjusted to the darkness. In the distance they could see a tiny yellow light bouncing like a moth against a window. Lucien held the signal lantern so Henri could see him hold his finger to his lips for silence, then signal for them to move forward. He pointed the light down, so it barely cast the shadow of their feet. They followed the flame in the distance, Henri walking with a pronounced waddle to cover the heavy steps of his limp and to compensate for not having his walking stick.

At times, the flame would disappear and they found themselves trying to find some speck in the distance, and Henri remembered, as a very small boy, closing his eyes to sleep at night, only to see images on the back of his eyelids, moving like ghosts. Not afterimages, not memories, but what he was actually seeing in the absolute darkness of night and childhood.

As they stepped carefully, quietly, over the even, dusty floors of the underground, those images came to him again. He remembered seeing electric blue moving among the black, and sometimes a face would come at him, not an imagined specter, nothing that he had conjured, but a real figure made of darkness and blue that would charge him from out of the infinite nothing, and he would cry out. That was the first time, he realized, there in the Catacombs, that he had seen Sacré Bleu. Not in a painting, or a church window, or a redhead’s scarf, but coming at him, out of the dark. And that was when he realized why he would kill the Colorman. Not because he was evil, or cruel, or because he kept a beautiful muse as a slave, but because he was frightening. Henri knew then he could, he would, put down the nightmare.

“Can you get us out of here with that map?” Lucien whispered, his lips nearly touching Henri’s ear.

“Maybe if we turn the lantern up,” Henri whispered back. “The chambers are supposed to be marked for the streets above.”

The Colorman’s light stopped bouncing for a second and Lucien reached back to stop Henri. He slid the lens of the signal lantern closed. The donkey brayed and with the echo they realized that they were not looking down a long tunnel at the Colorman’s light but through a vast, open chamber. Ever so gently, slowly, using his palm to dampen the sound, Henri closed the breech of the shotgun. They froze with the faint click, but what they thought was the Colorman reacting to their presence was, in fact, his playing his lantern over a wall, revealing a heavy brass ring set in the stone.

The Colorman set down his lamp, grasped the ring with both hands, and backed away, pulling what appeared to be a piece of the stone wall with him. The painters scurried forward with the cover of the noise, then paused when the Colorman turned to pick up his lantern. They were barely fifty meters away now; every scrape of the Colorman’s foot, every snort of the donkey, sounded as if it were inside their heads.

The Colorman walked out of their sight, into a passageway or a room, perhaps, but the donkey waited by the open portal.

Lucien set the signal lantern on the ground, then leaned in until he felt Henri’s hat brim against the bridge of his nose and whispered, “Please, do not shoot me.”

He felt his friend shake his head, even heard him smile, something he hadn’t thought possible up until then, and they crept forward, shoulder to shoulder. When they were only twenty meters away, Henri paused and cocked one of the hammers of the shotgun. The donkey flinched at the sound of the click.