Salt (28 page)

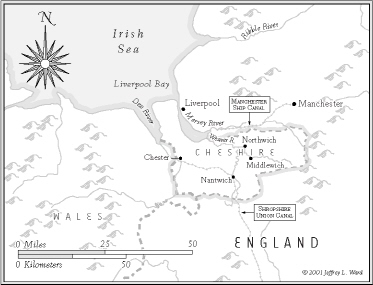

In time, Hellath du acquired the Anglo Saxon name Northwich, northern saltworks. Anglo Saxons called a saltworks a

wich

, and any place in England where the name ends in “wich” at one time produced salt. Hellath Wenn became Nantwich, and between Nantwich and Northwich was Middlewich.

By the ninth century, the area by the mouth of the Mersey, Cheshire, had become an important salt-producing region. The commercial center was Chester, where, in the eleventh century, the Roman-built fort was the last Saxon fortress to fall to William the Conqueror, completing the Norman conquest of England. In 1070, to crush the resistance, the Normans destroyed Chester and its saltworks, and in the decades that it took Chester to rebuild, Droitwich, south of Cheshire in Worcestershire, emerged as England’s leading salt producer.

C

HESTER WAS ON

the River Dee, which had an estuary that provided a deepwater port similar to that of the Mersey. Once Liverpool was founded on the Mersey, the two towns, with their two parallel rivers only a few miles apart, were competitors until the Dee began silting up and all the trade shifted to Liverpool.

For centuries, Bristol was a more important port, even a more important salt port, than Liverpool. This was due not to the exportation of British salt, but to the many ships carrying imported Portuguese and French sea salt that docked there. British salt-works could not provide the sea salt needed for British fisheries. Even when the English made a special high-quality salt for the cure of the best herring, a salt called white on white, they made it with French sea salt, dissolving the French salt in water and reevaporating it to remove impurities.

The market for salt fish proved more durable than the religious convictions that created it. Even after 1533, when Henry VIII broke with the Roman Church, a lenten meat eater was still subject to an array of penalties including three months’ imprisonment and public humiliation. By this time the motivation was less religious than economic—the government wanted to support the fishing industry. A 1563 proposal to extend the lean days to twice a week, adding Wednesday to Friday, was supported by the argument that it would build up the fishing fleet. It took twenty-two years of debate, but the idea of a second fast day was finally dropped in 1585. The English people were growing weary of the fast laws, and the Church adapted. The selling of permits to eat meat on fast days was becoming a profitable source of Church revenue.

In 1682, John Collins, an accountant to the British Royal Fishery, wrote a book called

Salt and Fishery, Discourse Thereof,

inspired by his seven years at sea, from 1642 to 1649, primarily serving with the Venetian fleet fighting the Turks. During this time, he was obliged to eat badly salted meat, evidently rotting, which he said “stunk.” This experience, he said, “begat in me a curiosity to pry into the nature of salt.”

Among his many recipes was the following for curing salmon. The recipe would still be good today, assuming a fifteen-year-old boy were available for long periods of jumping. Though the fish is from the Scottish-Northumberland border, the salt specified, as was usually the case for curing fish, was French sea salt:

The salmon cured at Berwick. As described by Benjamin Watson, merchant.

1. They are commonly caught from

Ladiday

[March 25, Feast of the Annunciation when the angel came to Mary] or

Michael-mas

[September 29, Saint Michael’s Day] either in the river Tweed or within three miles or less off at sea against Berwick.

2. Those caught in the upper part of the river. Brought by horseback to lower part. And those on the lower part thereof on boats to Berwick, fresh.

3. Then they are laid in a pav’d yard, where for curing there are ready 2 splitters and 4 washers.

4. The splitters immediately split them beginning at the tail and continuing to the head, close by the back fin, leaving the Chine of salmon on the under side [the belly intact], taking the guts clear out and the gils out of the head, without defacing the least fin and also take out a small bone from the underside, whereby they get to the blood to wash it away.

5. Afterward the fish is put into a great tub, and washed outside and inside and scraped with a mussuel shell or a thin iron like it; and from thence put into another tub of clean water, where they are washed and scraped again, and from thence taken out, and laid upon wooden forms, there to lie and dry for four hours.

6. Thence they are carried into the cellars, where they are opened, or layed into a great vat or pipe with the skinside downward and covered all over with French salt and the like upon another lay and so up to the top and are there to remain six weeks. In which time tis found by experience, they will be suffeciently salted.

7. Then a dried calves’ skin is to be laid on at the top of the Cask, with Stones upon it to keep them down; upon the removal thereof, after 40 days or thereabouts, there will appear a scum at the top about two inches deep, to be scum’d off or taken away.

8. Then the fish is to be taken out and washed in the pickle, which being done, they are to be carefully laid into barrels, and betwixt every lay, so much salt sprinkled of the remaining melted salt in the vats, as will keep them from sticking together. And after the barrel is one quarter full, is to be stamped or leaped upon by a youth of about 15 years old or thereabouts, being coverede with a calves skin, the like at half full, and also when quite full.

9. Then a little salt is to be laid on the top and so to be headed up; and then the Cask is to be hooped by the cooper and blown til it be tight.

10. Then a bunghole to be made in the middle of the barrel, about which is to be put a ruff or roll of clay, to serve as a Tonnel whereby frequently to fill the barrel with the pickle that is left in the vat, which will cause the oyle to swim; which ought to be frequently scummed off, and serves for greasing of wool. And thus after 10 or 12 days to be bounded up as sufficiently cured, and fit for exportation.—

John Collins,

Salt and Fishery, Discourse Thereof,

1682

E

VEN WITHOUT FISH,

Cheshire salt had ample uses. Crops to feed both humans and livestock could only be provided until the November harvest. The animals would then be slaughtered and salted to last until spring grasses could support a new herd. Animals were slaughtered on Martinmas, November 10, the Saint Day of Martin, an austere Roman soldier in Gaul who converted to Christianity and became the patron saint of reformed drunkards. Pre-Christian religions also marked November 10 as the day on which animals were slaughtered and salted for the winter, followed by a celebration for which, if they too converted, Saint Martin could grant forgiveness.

English food was extremely salted. Bacon had to be soaked before using.

Take the whitest and youngest bacon and cutting away the sward [rind] cut the collops [slabs] into thin slices, lay them in a dish, and put hot water into them, and so let them stand an hour or two, for that will take away the extreme saltinesse.—

Gervase Markham,

The English Huswife,

1648

Vegetables were also put up in salt to be used throughout the winter, and they too had to be refreshed before use. John Evelyn, a notable seventeenth-century English scholar who argued for more vegetables and less meat, gave this recipe for preserving green beans:

Take such as are fresh young and approaching their full growth. Put them into a strong brine of white-wine vinegar and salt able to bear an egg. Cover them very close, and so will they be preserved twelve months: but a month before you use them, take out what quantity you think sufficient for your spending a quarter of a year (for so long the second pickle will keep them sound) and boil them in a skillet of fresh water, till they begin to look green, as they soon will do. Then placing them one by one, (to drain upon a clean course napkin) range them row by row in a jarr, and cover them with vinegar, and what spices you please; some weight being laid upon them to keep them under the pickle. Thus you may preserve French beans, harico’s etc. the whole year about.—

John Evelyn,

Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets,

1699

Butter was also very salty. A 1305 recipe from the estate of the bishop of Winchester called for a pound of salt to be added for every ten pounds of butter. This would produce a butter as salty as Roman garum. The salt was to preserve the butter rather than for taste, and numerous medieval writers gave recipes for desalting butter before using, which often entailed mixing with fresh butter.

Butter has the same improbable myth of origin as cheese, that it accidentally got churned in the animal skins of central Asian nomads. Easily spoiled in sunlight, it was a northern food. The Celts and the Vikings, and their descendants, the Normans, are credited with popularizing butter in northern Europe. Southerners remained suspicious and for centuries maintained that the reason more cases of leprosy were found in the north was that northerners ate butter. Health-conscious southern clergy and noblemen, when they had to travel to northern Europe, would guard against the dreaded disease by bringing their own olive oil with them.

With no refrigeration, unsalted butter quickly becomes rancid. Even the butter sold as “sweet” was lightly salted. The English did have a specialty called May butter, which was fresh spring butter left unsalted in the sunlight for days. The sunlight would destroy the carotene, turning the butter white, and along with the pigment would go all of its vitamin A. It would become rancid and, no doubt, smell rancid. But inexplicably, in the Middle Ages May butter was considered a health food.

In the Middle Ages, yellow flowers of various species were salted and kept in earthen pots and beaten to extract a juice to color butter that had lost its carotene. Later, after Columbus’s voyages, annatto seeds were used. These seeds are still used by large American dairies, not to conceal rancid butter but because they believe the consumer wants a consistent dark yellow color.

The English passed laws against selling rancid butter. A 1396 law outlawed the use of salted yellow flowers. In 1662, a butter law was passed in England to establish standards. It allowed mixing rancid butter with good and specified that butter could only be salted with fine, not coarse-grained, salt, and it had to be packed with the producers’ first and last name clearly marked.

To preserve butter fresh for long keeping.

Make a brine as before described (salt enough to float an egg) and keep the butter sunk in it. About the beginning of May I caused this to be put into practice and potted up many lumps of butter bought fresh out of the market, and they all kept sweet, fresh.—

John Collins,

Salt and Fishery, Discourse Thereof,

1682

Other books

Veronica Mars by Rob Thomas

McLevy by James McLevy

Gemini Rising (Mischievous Malamute Mystery Series, Book 1) by Harley Christensen

I'm Thinking of Ending Things by Iain Reid

Sudan: A Novel by Ninie Hammon

Stepbrother Bastard by Colleen Masters

Return To Pandora: Book 1 in The Pandora Series by Smith, Kayla

Hatchet Men: The Story of the Tong Wars in San Francisco’s Chinatown by Dillon, Richard

Her Montana Man by Cheryl St.john