Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (42 page)

Read Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Online

Authors: Keith Lowe

Where Ukrainians and Łemkos did come across others like them, opportunities for mutual support, or even basic socializing, were rare. Official paranoia about the UPA had led to rules banning Ukrainian speakers from gathering in groups of more than a few people. Anyone caught speaking Ukrainian to someone else was automatically suspected of conspiracy. The Orthodox and Uniate churches were also banned, obliging Ukrainians to worship in a foreign tongue, in Catholic churches, or not at all.

Since the point of Operation Vistula was to assimilate Ukrainians into the Polish Communist state, children were in some ways the main focus of the authorities’ attentions. All children were forced to speak Polish at school, and Ukrainian literature was banned. Boys and girls caught speaking Ukrainian were reprimanded and sometimes punished. They were often given compulsory classes in Catholicism, as well as the usual Stalinist Communist indoctrination that was a part of every child’s education. Anything that revealed an alternative identity to the official Polish one was forbidden.

47

And yet, for all this, assimilation was impossible because their classmates often would not let them forget that they were

not

Polish. Children laughed at their accents, taunted them, and sometimes physically bullied them. ‘Ukrainian’ children were not invited to Polish children’s houses. Their difference from their classmates, and their isolation from any other children like themselves, made their situation quite similar to that of the ‘German’ children in Scandinavia. While there do not yet appear to have been studies into the life chances of these children compared with others, as there have been in Norway, it would be reasonable to assume that they probably suffered similarly high rates of anxiety, stress and depression in later life. Even more than the children of Germans in Norway, today many Ukrainians once again openly speak of themselves as a distinct group in Polish society – something that would have been unthinkable in the early 1950s.

The one experience that united all these people – and indeed all of the millions of others who were displaced from their lands after the Second World War – was a desire to return ‘home’.

48

This was, however, the one act that was forbidden above all others. Those who tried to return to their villages in Galicia found themselves faced with angry militiamen, and were threatened with violence or imprisonment. For others, there was simply no point. In the absence of the communities they had grown up with, their villages were no longer the idealized places they remembered. When Olga Zdanowicz tried to visit Gr ziowa many years later she found nothing there. ‘The village had been burnt – it didn’t exist any more.’

ziowa many years later she found nothing there. ‘The village had been burnt – it didn’t exist any more.’

49

The ethnic cleansing of Poland in 1947 is not something that can be considered in isolation. It was a product of many years of civil war, and more than seven years of racial violence that had begun almost as soon as the Germans had invaded the west of the country in 1939. It saw its foundation in the Holocaust of Polish Jews, particularly in the massacres in Volhynia, and the collaboration of Ukrainian nationalists in these and subsequent atrocities. After the war, the expulsion of Poland’s ethnic minorities was carried out with the explicit help of the Soviet Union, but the subsequent displacement and assimilation of Ukrainians and Łemkos was something that Poles conducted on their own initiative. Operation Vistula was effectively the final act in a racial war begun by Hitler, continued by Stalin and completed by the Polish authorities.

By the end of 1947 there were barely any ethnic minorities left in Poland. Ironically, given that Ukrainians had been responsible for much of the initial impetus, the country was far more ethnically homogeneous than its neighbour. The ‘Ukraine for Ukrainians’ espoused by the OUN was never achieved – particularly in the eastern parts of the republic, which kept a large Polish and Jewish minority even while western Ukraine was busy exchanging populations with Poland. ‘Poland for the Polish’, by contrast, was by the end of the 1940s not merely an aspiration, but a fact.

This process, which destroyed centuries of cultural diversity in just a few short years, was accomplished in five stages. The first was the Holocaust of the Jews, brought about by the Nazis but facilitated by Polish anti-Semitism. The second was the harassment of Poland’s returning Jews, which, as I discussed in the last chapter, caused them to flee not only Poland but Europe as a whole. The third and fourth were the ejection of Ukrainians and Łemkos in 1944 – 6, and their assimilation during Operation Vistula in 1947.

The final piece of the ethnic jigsaw in Poland, and one that I have not yet touched on, was the expulsion of the Germans. This, along with similar actions across the whole of Europe by other countries, is the subject of the next chapter.

The Expulsion of the Germans

The eastern border of Poland was not the only one to move in 1945. When the Big Three met at Tehran they also discussed what would happen to Poland’s western border. Churchill and Roosevelt were keen to compensate the Poles for what they would lose to Stalin by giving them parts of Germany and East Prussia instead. Churchill explained this proposal in a late-night session on the first day of the conference. ‘Poland might move westwards,’ he said, ‘like soldiers taking two steps “left close”. If Poland trod on some German toes, that could not be helped …’ To demonstrate what he meant, he placed a row of three matchsticks on the table and moved them each to the left. In other words, what Stalin took on the eastern side of Poland, the international community would give back on the western side.

1

Stalin was delighted with this idea, not only because it legitimized his seizure of Poland’s eastern borderlands, but because it pushed the demarcation line between Moscow and the Western Allies even further westwards. The only nation to lose substantial amounts of territory would be Germany, for whom it was regarded as a fitting punishment.

Once again, there was no consultation of the ‘freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned’, as promised by the Atlantic Charter. Such a consultation amongst the people of eastern Germany was naturally impossible while the war was on – but none of the superpowers considered it necessary to wait until after the war was over before pushing ahead. As the British Foreign Secretary stated to Parliament in justification of these plans, ‘There are certain parts of the Atlantic Charter which refer in set terms to victor and vanquished alike … But we cannot admit that Germany can claim … that any part of the Charter applies to her.’

2

Discussions about the borders between Poland and Germany therefore continued at Yalta at the beginning of 1945, and were concluded – as far as they would ever be concluded – at Potsdam the following summer.

As a result of these discussions, everything east of the Oder and Neisse rivers would become Polish, including the ancient German provinces of Pomerania, East Brandenburg, Lower and Upper Silesia, most of East Prussia (apart from a portion that Russia would keep for herself), and the port of Danzig. All of these areas had been considered German for hundreds of years, and were populated almost exclusively by German people – more than 11 million of them, according to the official figures.

3

The consequences for these people would be momentous. Given the history of German minorities within other countries, and the way that these minorities had been used by Hitler as an excuse to foment war, it was unthinkable that 11 million Germans would be allowed to continue living within the borders of the new Poland. As Churchill put it, when discussing the subject at Yalta, ‘it would be a pity to stuff the Polish goose so full of German food that it got indigestion’.

4

It was understood by all parties that these Germans would have to be removed.

When concerns were raised at Yalta about the practicality, and the humanity, of expelling such large numbers of people from their ancestral homelands, Stalin remarked blandly that most of the Germans in these regions had ‘already run away from the Red Army’. Broadly speaking, he was correct – the bulk of the populations in these areas

had

fled in fear of Soviet vengeance. But by the end of the war there were still some 4.4 million Germans living there, and in the immediate aftermath of the war, a further 1.25 million would return – mostly to Silesia and East Prussia – in the belief that they would be able to pick up their old lives. According to Soviet plans

all

these people would either be conscripted as forced labour to pay off German war reparations, or be removed.

5

Strictly speaking, the Soviets and the Poles were not supposed to start expelling Germans from these areas until after the borders were finalized. Even the provisional borders were not agreed upon until the Potsdam conference in the summer of 1945. It was expected that the final borders would be drawn once a peace settlement with Germany was signed by all the Allies. But because of the breakdown of relations between the Soviets and the West during the Cold War, and the consequent partition of Germany, such a peace treaty would not actually be signed for another forty-five years.

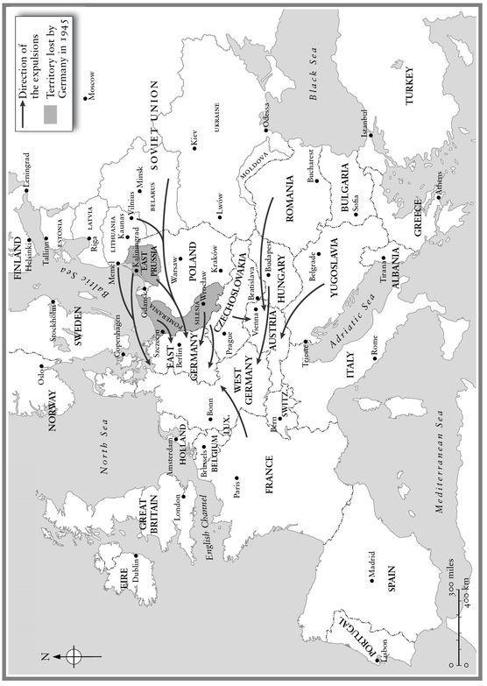

6. The expulsion of the Germans

In the meantime, the Poles and the Soviets would embark on their programme of expulsions regardless of international agreements. This became evident to the American ambassador, Arthur Bliss Lane, when he visited Wrocław in the early autumn of 1945. Wrocław, which until just a few months before had been the German city of Breslau, was already in the advanced stages of Polonization:

Germans were being forcibly deported daily to German territory. It was obvious that the Poles did not consider that they were occupying Wrocław temporarily, subject to final approval by the peace conference. All German signs were being removed and replaced by those in the Polish language. Poles were being brought into Wrocław from other parts of Poland to replace the repatriated Germans.

6

In fact, expulsions across the region had already been taking place for months by this time. Almost as soon as the war was over Poles began evicting Germans from their homes and claiming their property for themselves. It was not only the Red Army that raped and robbed Germans with abandon, but Poles too. In the cities, such as Szczecin (Stettin), Gdansk (Danzig) and Wrocław, Germans were herded into ghettos – partly so that Poles could take over their properties without a fuss, but also for their own protection.

7

In many areas Germans were rounded up and put into camps, either for use as slave labour or to be held until they could be officially deported. Some Poles were too impatient to wait for official permission, however, and began to hound whole communities of Germans across the border. According to official Polish records, in the last two weeks of June 1945 alone, 274,206 Germans were unlawfully deported across the Oder into Germany.

8

Such actions were by no means unique to Poland. In the spring and summer of 1945 the Czechs were busy driving hundreds of thousands of Sudeten Germans over their borders in a similarly frenzied way. The suddenness with which these ‘lightning’ expulsions were carried out demonstrates their popular nature, especially in Czechoslovakia: they were not events organized by the central authorities, but spontaneous expulsions sparked by local hatreds.

9

The urgency that characterized them implies that Poles and Czechs alike were eager to get rid of their German minorities before any outside agency stepped in to stop them doing so.

It was for this reason that the Big Three felt obliged to make a formal declaration on the way that the transfer of Germans was to be carried out. At Potsdam, in July and August 1945 they demanded a halt to all expulsions from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary until such time as they could be undertaken ‘in an orderly and humane manner’. It was not only the brutal way that these people were being expelled that was the problem – it was also the inability of the Allies within Germany to cope with the huge influx of refugees. They needed time to organize a system for integrating these newcomers, and dispersing them equitably throughout the different zones of Germany.