Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (47 page)

Read Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Online

Authors: Keith Lowe

Trucks drove up bringing other groups of prisoners. As the guards started to unload them, the volume of rifle and machine gun fire increased tremendously because these prisoners made a break for it as soon as they hit the ground. Although my hands were still bound behind my back, I also took off at a run. Bullets were whacking into the trees and cutting the shrubbery all around me. I tripped over a fallen branch and fell down headlong. Probably this saved me, because the guards evidently thought that I was accounted for and turned their attention elsewhere.

15

It is obvious from accounts like this that, far from being the actions of a few isolated individuals, the killing of Croatian prisoners was the work of entire units of men. It was also fairly well organized. Prisoners were executed not only individually and in small groups but on a massive scale: slaughter like this would not have been possible without an element of central organization by authorities high up the Partisan chain of command.

The local headquarters of these authorities appear to have been at the nearby town of Maribor. Here and at other centres in Slovenia, Partisan troops followed a standard process before liquidating their prisoners. First, an elementary form of selection was made, initially to separate out the civilians from the soldiers, then to separate the Ustasha troops from the ordinary

domobrans

or regulars, and finally to sort the officers from the rank and file.

16

The ‘least guilty’ were then loaded on trains to take them back towards Celje and Zagreb. Tens of thousands were sent on a series of forced marches that could last for days or even weeks to prison camps across the country. Some groups of men were retained locally as forced labour to carry out heavy or unpleasant tasks. But for the rest, this was the end of the road.

Near to the town were long lines of anti-tank trenches, which had been dug by German troops as a last-ditch defence against the Partisans. Prisoners were brought here by the truckload, where they were lined up along the edge of the trench and shot. These prisoners knew precisely what lay in store for them, because they could see the corpses of previous groups of prisoners lying at the bottom of the trenches. Many of them had been stripped of all their clothes. They had their hands bound behind their backs to prevent them trying to escape or lash out at their guards.

The following account is by a Croatian officer who, like many who escaped Yugoslavia but still had relatives there during the Cold War, wished to remain anonymous.

In the evening the Partisans undressed us, tied our hands behind our backs with a wire, and then tied us two and two. After that we were taken in trucks to the east of Maribor. I managed to untie my hands but was still tied to the other officer. We were brought to huge ditches where there were already dead bodies piled. The Partisans started shooting at our backs. Fast as lightning, I threw myself on top of the dead bodies. More dead bodies fell on me. When the Partisans were through shooting our group, they left. They did not bury us because there was room for more. So they went to Maribor for more victims. I untied myself from my dead partner and crawled out of this mass grave. I was naked, covered with blood of other victims, and so full of fear that I could not walk very far. I climbed a tree not far from the execution place. Three more times Partisans arrived with officers and priests and killed them all. When the sun started to rise, I went away.

17

The killing at Maribor lasted several days, and when the anti-tank trenches were full special burial squads were detailed to pile earth across the top of them and then level them off. Bodies were also buried in shell holes, bomb craters and specially dug mass graves.

One former Partisan, who later fled Yugoslavia, gave a graphic description of what it was like to work on one of these burial parties.

As we were performing our grim duty, another group was detailed to dig out a large hole that began where the trenches ended. To my horror I saw that this pit, too, was full of bodies. Since the dead in this hole were quite stiff or already putrefying, they probably had been killed days before …

We were still engaged in the task of burial at 5:00PM, when a hundred prisoners were brought to the newly excavated abattoir. We were told that they were going to help us inter the dead. But then these prisoners were lined up at the edge of the hole where the older corpses lay. Next they were looted of what belongings they had. Finally, the hundred prisoners were machine-gunned. I watched this slaughter from a distance of one hundred yards or less. Some of the prisoners threw themselves down flat and escaped the machine gun fire. They pretended to be dead, but the Partisans went from one apparent corpse to another and ran their bayonets through everyone whom they suspected of being alive. Screams rent the air, providing grim evidence that those who had dodged the machine gun fire had not eluded death for long. All of the new victims were thrown into the hole on top of the old corpses. Then the Partisans directed several more bursts of machine gun fire into the pile of bodies, just to make sure that they had not left anyone alive.

18

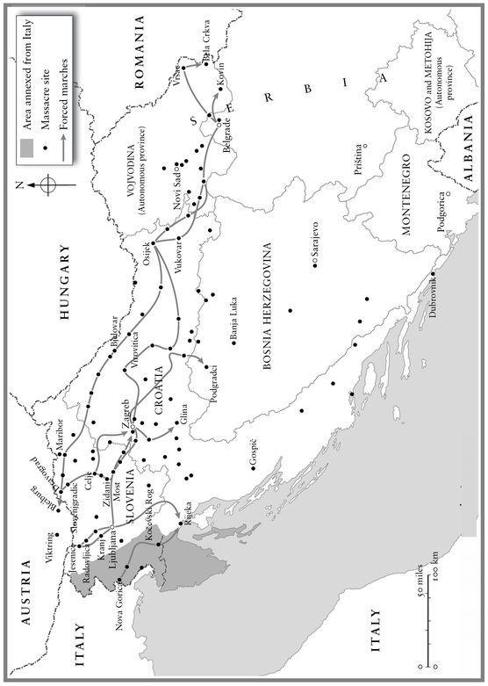

7. Massacre sites in Yugoslavia, 1945

According to the demographer Vladimir Žerjavi , who is widely considered to be the most objective and reliable authority on Yugoslavia’s war losses, some 50,000 to 60,000 collaborationists, mostly Croatian and Muslim troops, were killed in the area between Bleiburg and Maribor in the days immediately following the end of the Second World War. This represents around a half of all those Yugoslav troops who surrendered to the Partisans along the Austrian border in May 1945.

, who is widely considered to be the most objective and reliable authority on Yugoslavia’s war losses, some 50,000 to 60,000 collaborationists, mostly Croatian and Muslim troops, were killed in the area between Bleiburg and Maribor in the days immediately following the end of the Second World War. This represents around a half of all those Yugoslav troops who surrendered to the Partisans along the Austrian border in May 1945.

19

Maribor was by no means the only place where such massacres occurred. The vast majority of the 12,000 members of the Slovenian National Army who had escaped to Austria, and who were then handed back to the Partisans by the British, were murdered in the forests near Ko evje. They were taken to the edge of deep ravines in the Kocevski Rog and either shot or thrown over the edge alive. The walls of the ravines were then dynamited in order to topple masses of rock onto the corpses below. According to eyewitnesses there was no discrimination between officers and ordinary soldiers, or between those of differing political persuasion: ‘There was no questioning of the prisoners, nor did any of them receive any kind of trial, nor was there any selection made among them. Everyone who was brought to Ko

evje. They were taken to the edge of deep ravines in the Kocevski Rog and either shot or thrown over the edge alive. The walls of the ravines were then dynamited in order to topple masses of rock onto the corpses below. According to eyewitnesses there was no discrimination between officers and ordinary soldiers, or between those of differing political persuasion: ‘There was no questioning of the prisoners, nor did any of them receive any kind of trial, nor was there any selection made among them. Everyone who was brought to Ko evje was doomed to die.’

evje was doomed to die.’

20

At least 8,000 to 9,000 Slovenian nationalists were killed in this way, as well as some Croatians, Montenegrin Chetniks and members of the three Serbian Volunteer Corps regiments.

21

There were also a handful of women amongst the victims, and around 200 members of the Ustasha youth movement aged between fourteen and sixteen.

22

Similar events occurred in an abyss at Podutik, only a few kilometres outside Ljubljana. Here, the mass of decomposing bodies began to contaminate Ljubljana’s water supply, so in June a group of German prisoners of war were made to exhume the bodies and bury them properly in freshly dug mass graves.

23

The Partisans used all and any methods in order to kill their victims. In Lasko and Hrastnik Croatian collaborators were thrown down mineshafts, and hand grenades thrown in after them.

24

In Rifnik, prisoners were driven into a bunker that was then blown up with them inside it.

25

In the prisoner-of-war camp at Bezigrad prisoners were locked inside an enclosed reservoir, which was then flooded until they were all drowned.

26

In Istria, on the border between Yugoslavia and Italy, hundreds of Italian prisoners were thrown down deep pits and ravines to their deaths.

27

Inevitably, as at Maribor, there were some who managed to survive. One survivor, who was shot along with hundreds of others at Kamnik, tells a story that, were it not for the terrifying circumstances, might seem almost comic. He and his fellow prisoners were told to form a circle, after which the guards opened fire on them. Despite being hit in the forehead he somehow survived. As he lay amongst his dead and dying comrades he heard the Partisans arguing amongst themselves.

They were quite upset because, when the fools lined us up in a circle and began firing they were spread out in a circle too, outside of ours. Thus, in effect, they were shooting one another as well as at us. Two Partisans were killed and two others severely wounded because of this bit of stupidity.

28

The sheer wealth of such testimonies is quite staggering. Some of them are difficult to believe, such as the claim by Milan Zajec that he spent five days in a mass grave before being able to escape, but the majority are not only plausible but contain numerous verifiable details.

29

They are corroborated by similar accounts from German prisoners, members of the local population where the massacres took place, and even from various Partisan documents and testimonies.

30

If any further evidence were necessary, it is provided by the scores of mass graves that have been located all over the region. Since the fall of communism in Yugoslavia some of these mass graves have been exhumed, and there are now many memorials across Slovenia and Croatia commemorating the deaths of Tito’s victims.

The biggest question that remains is what motivated these massacres? Was it merely revenge against former military opponents, or rough justice for a regime that had been responsible for starting the cycle of atrocity in the first place? Were the killings politically motivated or the result of ethnic hatred? The simple answer is that all of these motives existed simultaneously, and are often indistinguishable from one another. The Ustasha regime in Croatia was built on an ideology of ultra-nationalism and ethnic hatred – the execution of soldiers and officials associated with this regime was therefore simultaneously a political and an ethnic act, and a fitting, if vengeful and often misdirected, punishment for the ethnic cleansing that the Ustashas themselves had carried out during the war.