Save the Cat! Strikes Back: More Trouble For... (7 page)

Read Save the Cat! Strikes Back: More Trouble For... Online

Authors: Blake Snyder

Tags: #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #Screenwriting

After having this pointed out, the writer realized his half-stepping ways had to go. By the time he came back with his pitch, it was the epic it should have been. And great!

Like Spidering, Half-Stepping shows another kind of fear and another hesitation: lack of confidence.

“Blurry Beats” is the same… but different.

This phenomenon belies the same fear, the same lack of boldness, but it is revealed not in avoiding hitting the beats, but by making them so quiet, so soft, so indefinite, we can't see them.

I find this often at the turning points of a script: the Breaks into Act Two and Three and at Midpoint. Yes, the writer kinda touches on those. And kinda hits the beats.

But I want more.

You cannot

slip

into Act Two. The Detective cannot

kinda

take the case, or suddenly

find himself

on the trail of the killer; he has to decide and step into action.

Likewise at Midpoint, the stakes can't

sorta

be raised. Big! Bold! Definite! That's how we like our plot points. And if you aren't delivering these, you aren't telling me the story. But what's really wrong is: You don't have the confidence in yourself to tell us a story that we know will work great. If only you thought so, too.

I'm your biggest fan — and I say: You can do it!

So you have your 15 beats worked out. Now what?

Well, that's easy.

In

Save the Cat!

I talk about how every movie has 40 Key Scenes and how I work out those scenes on “The Board.” This simple

corkboard has been the single most useful tool of my career. For those going from logline, to 15 beats, to 40 scenes, it's on The Board where it all comes together, and where we see what you've really got. But could I show writers my shortcuts to turn “15 into 40” in the classroom — and in this book?

The answer is: Yes!

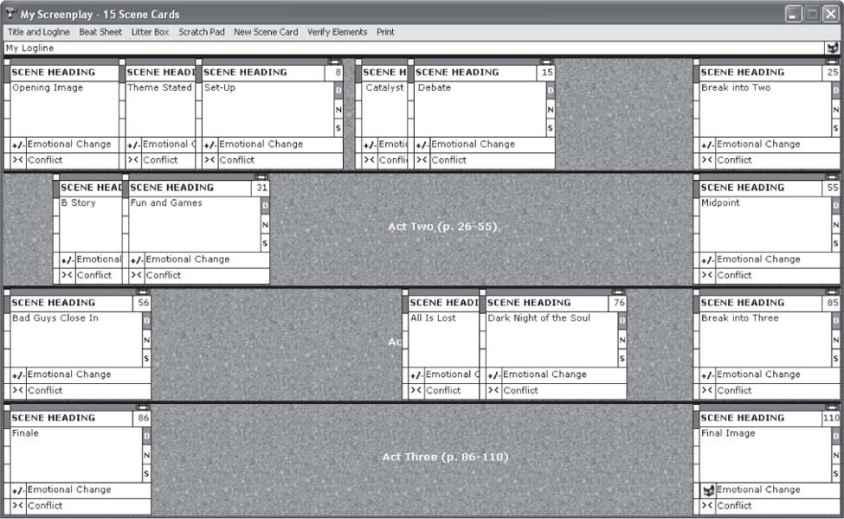

For those who want an overview of what a movie is, The Board (on pages 32 and 33) is gorgeous. Please note four rows representing Act One, the first half of Act Two, the second half of Act Two, and Act Three. And look how perfectly the 15 beats fit here. But now we have to make actual scenes, 40 of them, and that begins by taking it row by row and “breaking out” key beats to flesh out the 10 scene cards per row we need.

Let's start with the first row that constitutes Act One. Take a look. If you've nailed the Beat Sheet you already have six cards out of ten: Opening Image, Theme Stated, Set-Up, Catalyst, Debate, and Break into Two.

We only need four more.

To find these, I “break out” the Set-Up card. Set-Up is where we introduce the hero and his world. You probably have a list of things you want in here to “set up” who he is. But what is the best way to organize those scenes?

Think:

at Home

,

at Work

, and

at Play

. “At Home, our hero lives alone; his neighbor hates him because he never takes his trashcans to the curb. “At Play,” let's say our hero is into bowling, so we're going to have a scene at the lanes with his pals to set that up. While “at Work” our hero's the guy whose secretary bosses

him

around! Think H, W, and P and suddenly that one card breaks out into three actual scenes. And if you revisit at least two of these settings in your “Debate” card, suddenly your six cards become the 10 Key Scenes you need in that row. And while Home, Work, and Play don't apply to

every

story (see the Glossary for a great example of how H, W, and P appears in

Gladiator

), it's an easy way to set up “the world,” and the problem-plagued hero we need to introduce.

The Board with its first 15 cards, representing each of the 15 beats.

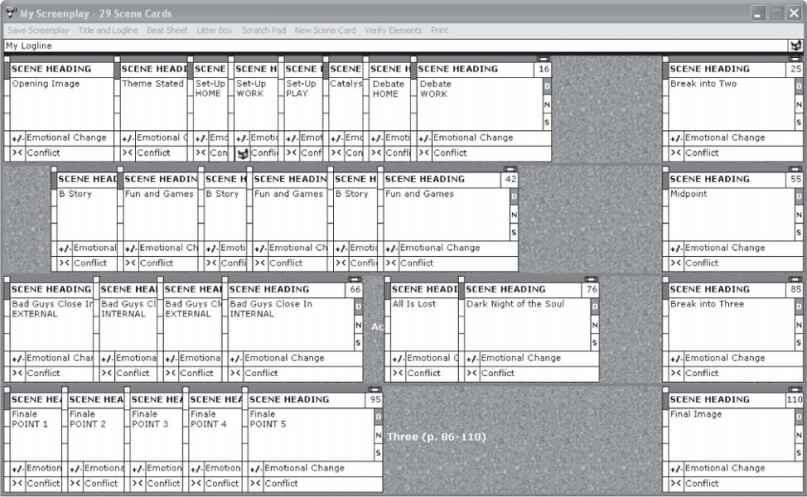

The Board with additional cards for Set-Up (at Home, Work & Play) and Debate (Home & Work) in Row 1, alternate B Story and Fun & Games cards in Row 2, alternate External and Internal scenes in Fun and Games in Row 3, and five cards for the five “Points” in the Five-Point Finale in Row 4. It's easy to add cards to your original 15!

Moving on to the second row, which represents the first half of Act Two from the Break into Two to Midpoint, we only have three cards appearing from the BS2: B Story, Fun and Games, and Midpoint. How can we get 10 cards from these? Well, again, you're farther along than you think.

What we're looking for in this row is a combination of B Story and Fun and Games as we move toward Midpoint. The B Story, which starts here, details how the hero meets the love interest, mentors, and sidekicks he'll need to “learn his lesson.” How the hero is adapting to this new, weird world is the Fun and Games. By pushing the hero forward and “shuffling” B Story and Fun and Games “set pieces” — B Story-Set Piece-B Story Set Piece — 10 cards are easy. This is seen in

The Matrix

when Neo (Keanu Reeves) crosses into the “hidden world” and meets a series of B Story mentors, and learns his new skills in Fun and Games that take him from cubicle-dwelling Joe to possibly “The One” by the Midpoint — all by shuffling B Story and set-pieces.

Row #3, which represents the second half of Act Two, may seem similarly daunting but is just as easy to fill in. Having a problem with Bad Guys Close In? Can't think of enough scenes to complete that part of your story? Think

External

and

Internal

. “Externally,” how is the actual “bad guy” putting pressure on your hero(e)s, and circling closer? What's the other half of that equation? Think “Internally.” How is the hero's “team” reacting to this pressure, and falling apart? Alternate these two sets of scenes by thinking E and I and you'll have more than enough. By the time you hit All Is Lost, Dark Night of the Soul, and Break into Three, you'll easily get 10 cards.

And as for what happens in Row #4 and Finale, I will have more to say on that subject, but here again, 10 cards is easy! It's just a matter of finding the five essential beats that make up the “Final Exam” the hero must undergo to prove he's learned the lesson, and can apply it himself.

What's great about this method is there is always a way to check your progress. We start with an idea, break it out to a logline, break that out to 15 beats, and then 40.

And if you want to try this at home, we've created a virtual Board in our best-selling

Save the Cat!

story structure software that is available on my website.

I love it! But even if you use an actual corkboard, push pins, and index cards, that still gets me excited. For whether you use the old-fashioned type, or our electronic version, being a “Master of the Board” never fails to create the most important result:

A story that resonates.

Whenever I get in front of a group of writers, I am forever worried about overloading them with information. I have this download of e-z-2-use tools I want to transfer from my brain to yours. It's only because I love my job, and love writers, that I want to push you right to that edge without going over the line. But there are times when I can see it in your eyes:

“I'm smiling, Blake, but in my brain… it's Chernobyl!”

This is why we now break the workshop into two separate units with the first weekend working out the 15 Beats and the “graduate” class, or “Board Class,” dealing with the 40 cards of The Board. But that was not always the case; in the early days of these workshops, we tried to do it all from idea to 15 beats to 40 scene cards in one weekend! I worry sometimes that I'll get a call from the relatives of one of those participants to ask what their family member means by “All Is Lost” — the words they keep mumbling from their bed in the facility where they've been held since my class.

Oh well! Trial and error.

“And we're walking, we're walking…”

In addition to working out what happens in each of the 40 cards, in the Board Class we also get into both “emotional shift”

(denoted by the +/- symbol on each scene card) and “conflict” (denoted by the >

In terms of the emotional shift (+/-), since every scene is a mini-story, each scene tracks change. Characters walk into a scene feeling one way and walk out feeling another. And while it may be too precise to show exactly what emotions those are in the planning stage, we can easily tag every scene as either positive or negative. And I encourage you to do just that. Often it's enough to say each scene is either a “+” or a “-” as it relates to Theme.

In the cataclysmic sci-fi epic

Deep Impact

, for instance, the Theme Stated question is: Will we survive the humongous comet streaking toward Earth? Each scene of the movie, believe it or not, alternates with “+” Yes we will or “-” No we won't. Yes. No. Yes. No. That's the thematic structure and the up and down of the emotional ride of that movie. My own

Blank Check

is like this, too. The Theme Stated of our family comedy about a boy who gets a million dollars is: “He who has the gold makes the rules!” Is it true? Well, scene by scene it fluctuates “+” Yes, it's true, money is fun! followed by “-” No, it's not, money isn't everything. Yes. No. Yes. No. All the way to the end.

Conflict (>) offers more challenge, especially when you're having a hard time finding it in your scenes. How many scenes have conflict in a 110-page screenplay? That's right. Every. Single. One. And yet finding that conflict in all scenes isn't easy. During an early class, the wonderful writer/actress Dorie Barton was working out cards for her L.A. thriller,

Migraine

, and we had a scene wherein the protag, a waitress hampered by severe headaches, explains to her boss what a “migraine” is. It's pure exposition, and the scene just lay there. Why? No conflict! Well, to fix that, we shoved some conflict in. We created a customer who, while the hero goes on explaining her condition, keeps banging on the counter. “Miss! More coffee over here! Miss! MISS!” The

forced conflict

of that

scene makes it play better — and reinforces the pained look on the hero's face as her migraine builds.

“Forced conflict” like this appears in lots of movies. My favorite example is in the Tom Cruise racecar epic,

Days of Thunder

. It's a simple scene: NASCAR driver Tom phones doctor Nicole Kidman, whom he just met, to ask her out on a date. Very dull. Aside from the conflict of “Will Nicole say yes?” what other conflict is there? So the writers have placed this scene in the break room at Tom's workplace, where Tom's co-workers get their coffee. Since everyone is curious about Tom, they keep busting in for another cup of java — and embarrassed Tom keeps pushing them out, wanting privacy. The scene now demands attention. Forced conflict can feel phony — Tom could make the call from the pay phone across the street, right? — but we get better at it with practice. Because we must put conflict into ALL our scenes!