Saving Henry (4 page)

Authors: Laurie Strongin

Henry's geneticist first suspected FA because of Henry's relatively low birth weight, extra thumb, and heart defect, which were not a coincidence. However, we learned that doctors usually fail to diagnose FA at birth, since few of them have experience with the disease, and also because there are a multitude of possible birth defects, it presents differently in different kids. Even identical twins born with FA can have differing birth defects. Some babies are missing thumbs or kidneys, have malformed digestive tracts, or have hearing loss. Some have no birth defects at all. The majority of children are diagnosed only after a series of infections or nosebleeds lead to a blood test that reveals aplastic anemia or bone-marrow failure.

Aplastic anemia, a condition in which the bone marrow does not produce enough red cells, white cells, or platelets, almost always develops in children with FA. It compromises the body's ability to fight infection, causes spontaneous bleeding and exhaustion, and ultimately leads to death. The most successful treatment for aplastic anemia is a hematopoietic stem-cell transplant with blood stem cells derived from the bone marrowâcommonly referred to as a bone-marrow transplant.

Although successful stem-cell transplants can cure aplastic ane

mia, Fanconi patients also have a much higher risk of other cancersâsuch as acute myeloid leukemia, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and cervical and liver cancerâthan the general population. So patients who are lucky enough to survive a stem-cell transplant, while unlikely to develop leukemia, are likely to face a subsequent diagnosis of one cancer or another, and must endure the medical challenges again and again.

Among the doctor's referrals was an organization, the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund (FARF), founded by Lynn and Dave Frohnmayerâparents of five children, three of whom were born with FAâwho had since devoted their lives to raising money and funding research. FARF also provides much-needed information and support to families who, like ours, unwittingly joined a club of which no one would choose to be a member. From our first conversation, Lynn and Dave provided us with comfort that we were not alone in our fight to save Henry. They also gave us an abundance of information about Fanconi anemia, and their friendship.

When we got the news about FA in early November 1995, my sister, Abby, had a one-week-old daughter, Rachel, and an eighteen-month-old son, Michael; my brother, Andrew, and his wife were expecting their first baby in five months; and Allen's sister, Jennifer, had a one-year-old, Hannah. No one knew who was and wasn't a carrier or who might already or soon have a child with a deadly disease. They visited geneticists and hugged their kids a little tighter as they anxiously awaited the test results. In every case, our family members were eventually told that they were lucky enough to have genes that did not foretell the premature death of their children.

Allen and I spent the first few months of Henry's life shopping for diapers, onesies, a breast pump, hematologists, cardiologists, and pediatric surgeons. We interviewed doctors in Washington; New York City; Hackensack, New Jersey; and Boston. We settled on a

cardiologist in Washington, a hematologist in Hackensack, a cardiac surgeon and a hand surgeon in Boston, and a Medela Pump In Style breast pump.

Henry, meanwhile, spent the first few weeks and months of his life doing the things that babies do. He learned to turn his head from side to side, roll over from his tummy to his back, play with his fingers and toes, and smile. He smiled when he heard my voice. He smiled when Allen or I held him. He smiled when we listened to good music. I was the first of the Ladies of the Pines to have a child, and Erica, Becca, and my neighbor Debbie Blumâalso a member and a pregnant one at thatâadored Henry. They stopped by all the time. Erica was playing with him one day in our family room, making faces and singing to him. Staring down at him, she exclaimed adoringly, “Laurie, this kid's smile is too big for his face!”

Abby, Rachel, Henry, and I spent a lot of time together those first few months. I'd strap Henry in the BabyBjörn and walk over to Abby's house, about a mile away, and we would head to Georgetown for coffee or lunch. Henry was happy, easy, and incredibly adorable. And most important, his defective heart did what it needed to do and he never turned blue, defying the predicted path and reassuring me that I could trust Allen's optimism.

And proving to us that Henry was extraordinary.

⢠Batman

⢠Cal Ripken

⢠Collecting baseball cards

⢠Traversing the monkey bars

⢠Going to Spring Training

⢠Flushing saline through his own IV lines

⢠Chocolate-chip pancakes

M

AKING

C

HOICES

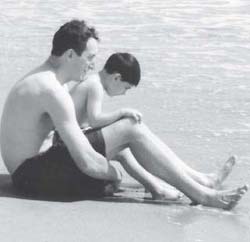

Allen and Henry ponder the surf in Bethany Beach, Delaware

The Strongin Goldberg Family

L

ong before the words “Fanconi anemia” entered my lexis, I had dreamed of having three kids, and always pictured myself surrounded by boys. My mother, Pat Strongin, is a great mom and a great role model. She is young at heart, active, and full of life; growing up, she took us kids biking, camping, swimming, and horseback riding. With her boundless energy and joy, her popularity extended well beyond the family to include all my friends who spent countless

hours hanging out in our childhood home. Even Allen later admitted that after meeting my mom, he decided to marry me. He saw signs of me in her and found her to be “really cool⦠for a mom.” My dad, meanwhile, has always been the Godfather of our family. He smokes cigars, likes a good glass of scotch, reads voraciously, thinks about things, and doles out instructions and wisdom. He is one of the most adventurous men I know. I had always imagined that I'd be the same type of parent to my kids that they had been to Abby, Andrew, and me: fun, love-filled, supportive, and completely comfortable with mayhem. I imagined a house, yard, and garage filled with sports equipment; a kitchen with plentiful snacks and family dinners; a playroom with games, drums, guitars, and a pinball machine; vacations at the beach; and baseball games on the weekends. Loud, crazy, spontaneous fun.

Allen and I wanted to have several children, but Fanconi anemia made family planning about a whole lot more than love and sex. All of a sudden, it was a complex puzzle of genes, statistical probability, prenatal testing, and life-or-death decisions. It wasn't just about creating life but about avoiding certain death. The very best prenatal care might be a good weapon against some diseases, like spina bifida, but it is useless against Fanconi anemia. Because Allen and I are both FA carriers, there was an uncomfortably high chance that we could have another baby with the disease. Although there was a 75 percent chance that our next baby would be healthy, our life experience taught us that statistics are predictions, not promises. After all, the chance of our having a baby with FA was 1 in 30,000. Once you hit a number like that, you stop taking comfort in the remoteness of a chance that something bad could happen.

Through conversations with FARF leadership and our growing list of doctors, as well as our own research, Allen and I understood that Henry would need open-heart surgery at around six months of age and a bone-marrow transplant probably by the time he turned

five. Though I was scared to death at the prospect of open-heart surgery, I understood that the bone-marrow transplant was the real challenge. Our best hopeâif not our only oneâthat Henry would survive a transplant was if we could find a perfectly matched stem-cell donor. The only perfectly matched donors are siblings.

At this time, in 1995, bone-marrow transplants from perfectly matched sibling donors had reported success rates of 85 percent. This meant that if we had another baby who did not inherit Fanconi anemia and whose bone marrow was compatible with Henry's, then Henry would probably survive. When the baby was born, doctors could collect its umbilical-cord blood through a painless and harmless procedure, transplant it to Henry, and silence the most lethal threat to his life.

In contrast, the success rate for a bone-marrow transplant from an unrelated donorâsomeone other than a siblingâwas around 18 percent, meaning that without a sibling donor, Henry would probably die. At the time, no one with his type of FA had ever survived a transplant without a perfectly matched sibling donor.

What this meant for us, in the simplest terms, was that Henry's life depended on our having another baby with two critical characteristics: the baby had to be Fanconi anemiaâfree, and needed to be a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match to Henry. HLA, also known as histocompatibility antigens, are genes that recognize whether a cell is foreign to the body. Any cell possessing an individual's HLA type is recognized as belonging to that person, whereas a cell with a different HLA type is identified as an invader. Like all invaders, these cells are unwelcome, and the resulting internal battle can cause mild to great bodily harm and even death.

HLA type is used to determine the compatibility of bone marrow, kidney, liver, pancreas, and heart for transplantation from one person to another. Compatibility between organ donor and recipient is judged by the number of HLA antigens found in the donor that are

shared by the recipient. In 1995, bone-marrow-transplant compatibility was determined by six HLA antigens, including two each of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR. Everyone acquires one set of three from each parent. Today, the testing is more sophisticated and the best donor would share eight antigens, which include HLA-C. The very best organ donor for Henry would be someone with the

exact

same HLA antigens. HLA type is inherited, and that is why siblings have the greatest likelihood of being perfectly matched at the HLA antigens and why they are therefore the ideal donors.

Nothing was guaranteed. Because, like Fanconi anemia, HLA type is genetic, the chance of another baby being a perfect HLA match to Henry was just 25 percent. But Fanconi anemia further diminished those odds. If the sibling also had FA, he or she would not only be disqualified as a stem-cell donor but would also suffer from the disease, would probably experience significant birth defects, and eventually need a transplant from a healthy sibling. The probability that we would have a healthy baby who would also be an HLA match to Henryâthe ideal-case scenarioâwas merely 18.75 percent, or one-quarter of the 75 percent chance that the baby would be healthy.

In other words, it was a long shot.

Â

A

llen and I talked a lot about having another child, weighing all of our options. The only absolute guarantee that our future children wouldn't have FA was if we adopted or did artificial insemination, using a donated sperm or donated eggs. Or, of course, we could decide to stop having children altogether. At the time, our inherent optimism combined with our determination not to let Fanconi anemia dictate every move, and our deep desire for more children, blinded us to those alternatives.

I thought a lot about my ability to provide not just a life for a new baby, but a good life, even in the worst of circumstances. We

knew it was a serious decision to have another child who was certain to experience extreme hardship and the potential loss of a sibling. I talked with Allen, perhaps more than he would have liked, about all the fears and uncertainties I felt.

“What are we doing? Are we being irresponsible, risking having another child with FA?” I asked him over dinner at Lebanese Taverna, our date-night destination; and again, a few days later, as we drove home from a visit to New York, where we had been shopping for doctors. “I know I want to have more kids, but our life is going to be so hard and I'm scared to bring another child into it. It's not like this baby is asking to be born,” I said. “We're going to bring him or her into a family filled with lots of love, to be sure, but also the guarantee of so much hardship with Henry's illness. I just don't know if that is the right thing to do.”

Allen listened, but he didn't share my concerns.

“Laurie, you don't have to take all that on right now. Henry is going to be fine. And our next baby is going to be healthy. And lucky. You know how much we love Henry? That's how much we're going to love the next one, too,” he responded.

In the end, I felt strongly that choosing to have another child meant that Allen and I were committing to surviving, even if Henry didn't, and it wasn't long before we arrived at our decision: We were going to have another child. Although we hoped our second child would be an HLA match to Henry, our main concern was that he or she would be healthy.

A few days later, during a walk through the neighborhood with Henry, I confided in my mom. “Allen and I talked about it. We're going to have another baby after Henry's heart surgery is over. I really want to have more kids,” I explained. “I don't want to let Fanconi take that away from me too.”

“Laurie, I'm so happy to hear that,” my mom said. “I

want

you

to have more kids. You should. You were meant to be a mother. You're a great mother. And any child of yours is one lucky kid.”

“But I'm scared,” I confessed. “I don't know what I'll do if that child has Fanconi, if I could live through that again. Knowing what's ahead of us, and what Henry faces⦠it's so hard.”

My mom stopped walking and took my hand in hers. “Laurie, you will do whatever you have to do. When you were just a year and a half old, Grandma said to me, âThat one has something special,' and you do.”

Â

B

efore I got pregnant again, I needed to survive Henry's open-heart surgery. Actually, I needed Henry to survive Henry's open-heart surgery. I knew that I wouldn't be able to sleep or eat while I sat in a waiting room worrying about whether Henry would make it through his time on a heart-lung machine and the recovery from his surgery. If I did get pregnant right away, I wanted to make sure our new baby was developing in the healthiest prenatal environment possible. Also, I knew I couldn't simultaneously handle the trauma of Henry's heart surgery while waiting for, and processing, prenatal test results that would tell us if our second child also had Fanconi anemia, which could be determined at the end of the first trimester.

Henry's open-heart surgery was scheduled for April 2, 1996, with Dr. Richard Jonas at Boston Children's Hospital. The days leading up to the trip, I packed Henry's stuff, asked our neighbors Rich and Jill Lane to pick up our mail and keep an eye on the house, called Erica and Becca to tell them I'd miss that month's Ladies of the Pines meeting, and desperately hoped for the best. A few days after we arrived, my parents, Allen's parents, and Abby joined us in Boston, where we had been meeting with doctors and preparing for the surgery. We had been told that we wouldn't be allowed to spend

the night at the hospital, so we checked into the Best Western Hotel immediately adjacent to it. The day before Henry's surgery, I took the advice of another mother, a friend's cousin whose son had endured the same procedure at the same hospital. She had encouraged us to visit the pediatric cardiac intensive care prior to his surgery, thinking that we needed to know what, exactly, we were in for.

Walking in there for the first time was as scary as hell. There were no private rooms, just curtains separating kidsâabout ten of themâall in perilous situations and fighting for their lives. The nursing station was central so that the staff could be at a child's bedside in a moment. Dazed, weary parents talked in hushed tones, and the kids were in drug-induced comas, resting while their hearts healed. It was an eerie quiet, interrupted only by the frightening, panicked clamor of pumps, machines, alarms.

On the morning of his surgery, we brought Henry to the hospital before the sun rose and sat with him until the anesthesiologists approached. They tickled him. They smiled at him. And then before we knew it, they were gone. With Henry.

We sat in the waiting room, waiting. Surrounded by untouched food, unopened magazines and books, our parents and my sister, we just sat. There was nothing to talk about other than the obvious, and we saw no point talking about that. So we sat in silence, and we waited.

With each major step, a nurse came to inform us of Henry's progress. He's under anesthesia. He's on oxygen. I was so scared, I honestly didn't know if I would get through it. When the nurse came to tell us he was on the heart-lung machine, all I heard was:

His heart isn't beating

.

Their hands are in there. They're touching his heart

. But then she returned, a few hours after it had begun, to tell us that he was off the heart-lung machine; that his heart was working again. He was being brought to the recovery room.

He is alive!

I don't know if those words actually passed my lips, but the way I

remember it, I yelled it more loudly and joyfully than anything I had ever shouted before.

Even if I had spent months in that pediatric intensive care unit trying to get comfortable with the images and the reality of what Henry would have to endure, nothing would have prepared me for what I saw when Henry first came out of surgery. It was terrifying. His whole body was swollen and his skin looked like it was made of plastic. White surgical tape held his oxygen mask in place. Dozens of tubes ran into and out of his body. The bandages covering his chest were soaked in blood. It was, as of that day, the most horrifying image I'd ever seen.

I leaned over his tiny body. “Please get through this,” I whispered to him. “I know it's only been five months, but I can't remember my life before you.”

Henry spent the next few days in his hospital bed, between two curtains that we could close for some privacy. He wore nothing but a diaper and lay completely motionless in a drug-induced paralysis. We could not hold him or hug him. We could merely stand there and stare and hope he'd wake up. There were lots of monitors beeping and flashing, recording his oxygen level and heart rate and blood gasses and, I imagine, other stuff. I studied the numbers, the charts, and the levels, trying to understand what they meant, what they could tell me. Hoping, desperately, that he was improving.

On the second morning, Allen and I arrived at the ICU and saw that the incubator next to Henry's was empty. I asked the nurse on duty what had happened to the newborn baby who was there the night before. It was a stupid question, perhaps, or at least an obvious one. The bed was stripped of its sheets, the medical equipment shut off. The nurse told us the boy's name: Henry. I felt a sharp pang of sadness for the tiny boy's parents, for his unlived life.

Over the next few days, my breasts ached from the desire to feed our Henry, but my milk had dried up because I was unwilling to

leave his bedside to pump milk that he was too weak to drink and that would just be thrown away. For the time being, his nutrition was delivered through one of the many tubes pumping fluids into and out of his tiny body. Were it not for the machines that indicated to the contrary, I would have thought he was dead.