Scar Tissue (64 page)

In the song “Otherside” on

Californication,

I wrote, “How long, how long will I slide/Separate my side/I don’t, I don’t believe it’s bad.” I don’t believe that drug addiction is inherently bad. It’s a really dark and heavy and destructive experience, but would I trade my experience for that of a normal person? Hell no. It was ugly, and there is nothing I know that hurts as bad, but I wouldn’t trade it for a minute. It’s that appreciation of every emotion in the spectrum that I live for. I don’t go out of my way to create it, but I have found a way to embrace all of it. It’s not about putting down any of these experiences, because now that I’ve had them, and now that I’m almost four years sober, I’m in a position to be of service to hundreds of other suffering people. All of those relapses, every one of those setbacks that would seem like unnecessary additions to an already tortured experience, are all going to be meaningful. I’m going to meet some other person along the way who was clean for some time and can’t get clean again, and I’ll be able to say, “I was there, I did that for years, I was going back and forth, and now . . .”

I went with Guy O to a kabbalah course the other night, and the lesson was about the four aspects of the human ego, which are symbolized by fire, water, air, and earth. Water represents the excessive desire for pleasure, and I’m a water sign, and that’s been my whole life. I’ve wanted to feel pleasure to the point of insanity. They call it getting high, because it’s wanting to know that higher level, that godlike level. You want to touch the heavens, you want to feel glory and euphoria, but the trick is that it takes work. You can’t buy it, you can’t get it on a street corner, you can’t steal it or inject it or shove it up your ass, you have to earn it. When I was a teenager and shooting speedballs, I wasn’t thinking, “I want to know God,” but deep down inside, maybe I did. Maybe I wanted to know what that light was all about and was taking the shortcut. That was the story of my life, even going back to my childhood in Michigan, when I’d get home from school by going through a neighbor’s backyard and jumping a fence. It didn’t matter if I got bitten by a dog or I ripped my pants on the fence post or I poked myself in the eye with a tree branch that I was crawling over, it was all about the shortcut. My whole life I took the shortcut, and I ended up lost.

Things are good now. Buster and I share a nice house. I’ve got a terrific group of supportive friends. And when it’s time to go out on the road, I’m surrounded by another group of supportive people. One of my main soul mates is Sat Hari. She came into our world in May 2000, when Flea brought her on tour to administer intravenous ozone therapy to him. Sat Hari is a nurse, an American Sikh, a sweet, incredibly sheltered, turban-wearing young lady. She looks like a female version of Flea, with the same gap-toothed smile, the same shape of face, the same color eyes, the same little pug nose. She’s maternal and she’s warm and she’s loving and she’s unassuming, a complete breath of fresh air and female energy, and I don’t mean sexual energy, at least not for me. For me she’s like a sister and mother and caretaker and nurse all in one.

Sat Hari endeared herself to everybody in the band and the crew, and she became the den mother to the entire organization. Everyone used her as their ultimate confidante, spilling their guts to her all day and all night about their deepest, darkest, most untellable secrets. We’ve all had an impact on her, too. She was a controlled, subservient Sikh who was told what she could and could not do, who she could and couldn’t talk to. We showed her a new world of meeting all these freethinking people who were out dancing and loving life. She flourished as a person and came out of her shell. During the

By the Way

tour, Sat Hari and John and I shared a bus, and it was a cozy, moving cocoon of happiness.

We extended that vibe into the arenas that we played. It was clear after our first few tours that the backstage areas were always cold, stark, fluorescent-lit concrete tombs, places where you wouldn’t want to spent two minutes. So for the

Californication

tour, we hired a woman named Lyssa Bloom who had a knack for beautifying these rooms. She laid down rugs, put up tapestries, covered the fluorescent lights, put in a portable stereo system, and set up a table of fresh fruits and vegetables and nuts and teas.

So now we hang out backstage before the show, and John, who became the official DJ of the area, programs the music. He and Flea get out their guitars and practice, and I do my vocal warm-ups. Then I make everyone tea and write out the set list. Sat Hari comes in and gives us ozone, and then we stretch on the floor and do a little meditation. We have all of these grounding rituals that keep growing and getting better and better.

Our final ritual before we go onstage is the soul circle. It’s funny how that’s evolved over the years. When we were this brash young band of Hollywood knuckleheads, we would get in a circle and slap one another in the face right before we went on. That got the juices flowing, for sure. Now we get in a circle and hold hands and do some meditation together, getting into why we’re there and what we need to be together. Someone might chime in with “Let’s do this one for the Gipper” or “There’s a thunderstorm outside, let’s tap into that.” There are times when Flea’s the one to give us little words of encouragement. Sometimes it’s up to me to crack a joke or make up a rhyme. Lately, John has become the most vocal member of the soul circle. Chad doesn’t usually instigate, but he’s there with a “hear, hear” thing.

All of these rituals ground me. But ironically, what grounds me constantly is my obsession with drugs. It’s funny—that first five-and-a-half-year period when I got sober, I never had any urgings to do drugs. The uncontrollable obsession that I’d experienced from the time I was eleven years old just vanished the first time I got clean. It was a true miracle. When I came out of my first rehab, the idea of getting high was a foreign concept to me. I could have sat there and stared a big mountain of cocaine in the face, and it would have meant nothing to me; a month before, I would have been shaking and sweating from the physical reaction alone. The way the sneaky motherfucker got his foot back in the door was through those experiences with prescribed painkillers.

Once I started relapsing, I would never get the gift of being relieved from the obsession of doing drugs again. This might seem like a tragic curse, but I look at the bright side of it: Now I have to work harder at my sobriety. When I was relieved of the obsession, I was doing very little work. Now I have no choice but to be more giving and more diligent and more committed, because a week doesn’t go by when I’m not visited by the idea of getting loaded.

For the first year of my newfound sobriety, all of 2001, the feeling of wanting to get high came to me every day. Especially later in the year, after Claire moved out, it got so bad that I couldn’t sleep. One night I got the closest I’d come to going back out there. I was home alone and there was a full moon out. I was writing the songs for

By the Way,

everything was going well, and I was feeling inspired. I took a stroll outside, and the night was clear, and I could see the alluring lights of downtown.

And I got ready to throw it all away one more time. I packed my little weekend backpack and left a note for my assistant to take care of Buster. I got my car keys and walked out of the house. I got as far as the porch and looked up at the moon, looked out at the city, then looked at my car and my backpack and thought, “I can’t do it. I can’t throw it away one more time,” and I went back inside.

In the past, once those wheels were set in motion, forget about it—floods, earthquakes, famines, locusts, nothing would have stopped me from my abhorrent rounds. But now I’d proved to myself that I could live with my obsession until it went away. I was willing to accept the fact that I thought about getting high on a regular basis, that I could watch a beer commercial and see that sweaty bottle with the cap popping off and actually want a beer (and still not drink one).

The good news is that by the second year, those cravings were about half as frequent, and by the third year, half as much again. I’m still a little bent, a little crooked, but all things considered, I can’t complain. After all those years of all kinds of abuse and crashing into trees at eighty miles an hour and jumping off buildings and living through overdoses and liver disease, I feel better now than I did ten years ago. I might have some scar tissue, but that’s all right, I’m still making progress. And when I do think, “Man, a fucking motel room with a couple of thousand dollars’ worth of narcotics would do me right,” I just look over at my dog and remember that Buster’s never seen me high.

AK would like to thank:

Larry Ratso Sloman for his constant and heartfelt thoughtfulness toward those he engaged to compile this story. Ratso’s wily investigative knack was invaluable for the construction of this project, but his consideration for the well-being of others was paramount to the bigger picture. God bless this talented man and his badass style.

Thanks also to bandmates, family members, friends, enemies, lovers, detractors, teachers, troublemakers, and God for making this story come true. I love all of you.

LS would like to thank:

Anthony for his incredible candor, sincerity, memory, and open-heartedness.

Michelle Dupont for the tea, sympathy, and everything else.

David Vigliano, Superagent.

Bob Miller, Leslie Wells, Muriel Tebid, and Elisa Lee at Hyperion.

Antonia Hodgson and Maddie Mogford in England.

Bo Gardner and Vanessa Hadibrata for all their help above and beyond the call.

Blackie Dammett and Peggy Idema for their gracious Midwestern hospitality.

Harry and Sandy Zimmerman and Hope Howard for the L.A. hospitality.

Michael Simmons for the EMS call.

All of AK’s friends and colleagues who gave so much of their time to reminisce, especially Flea, John Frusciante, Rick Rubin, Guy O, Louie Mathieu, Sherry Rogers, Pete Weiss, Bob Forrest, Kim Jones, Ione Skye, Carmen Hawk, Jaime Rishar, Claire Essex, Heidi Klum, Lindy Goetz, Eric Greenspan, Jack Sherman, Jack Irons, Cliff Martinez, D.H. Peligro, Mark Johnson, Dick Rude, Gage, Brendan Mullen, John Pochna, Keith Barry, Keith Morris, Alan Bashara, Gary Allen, Dave Jerden, Dave Rat, Trip Brown, Tequila Mockingbird, Grandpa Ted, Julie Simmons, Jennifer Korman, Nate Oliver, Donde Bastone, Chris Hoy, Pleasant Gehman, Iris Berry, Sat Hari, and Ava Stander.

Cliff Bernstein, Peter Mensch and Gail Fine at Q-Prime.

Jill Matheson, Akasha Jelani, and Bernadette Fiorella for their amazing transcribing skills.

Langer’s for the best pastrami west of Second Ave.

Mitch Blank and Jeff Friedman for the emergency tape repair.

Lucy and Buster for the canine companionship.

And, most of all, my wonderful wife Christy, who kept the home fires burning.

Wearing a shirt that I wish I still had. It probably came from my faraway dad. I seem to be honing and sharpening my strategic powers over a game of Don’t Break the Ice. 2247 Paris Street S.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan. Approximately 1971.

Mom used to sit me down for the occasional correspondence with my renegade pops. Little did I know I was encouraging the sale of weed by the kilo. Either way, I was California dreaming at the tender age of six.

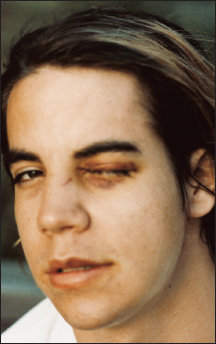

At the age of twenty-one, I was already an angel away from killing myself behind the wheel of my mother’s Subaru. Nobody told me that dope-sick junkies shouldn’t drink three buckets of beer and try to drive home. I played a show with the Red Hots in New York City less than a week later. 1984.

Like father, like son. I’ve got to tell you, little boys love their dads. It’s a fact. Doesn’t matter what the scenario is, we love our dads. And need ’em. This is one of the rare but sacred visits my father made to my house on Paris Street. Early 1970s.