Scene of the Crime (17 page)

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

A

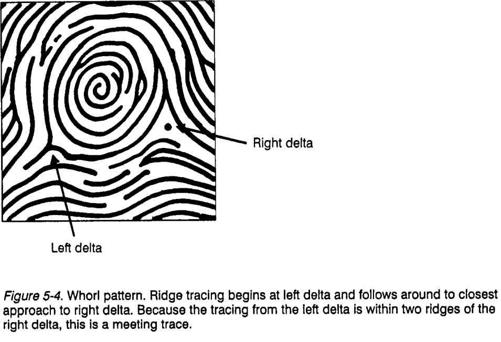

plain whorl

would be shown as P plus the tracing. Thus, an inner trace plain whorl would be listed as PI.

A

central pocket loop whorl

would be listed as C plus the tracing. Thus a central pocket loop whorl with a meeting trace (which is very uncommon—a central pocket loop is most often an inner or outer trace) would be listed as CM.

A

double loop whorl

would be listed as D plus the tracing. Thus a double loop whorl with an outer trace would be listed as DO.

An

accidental—

which effectively is any print that does not fall into any of the normal classifications-would be listed as X plus the tracing; if there are more than two deltas, the tracing will be from the extreme left delta to the extreme right delta. Thus, an accidental with an outer trace would be listed as XO.

An

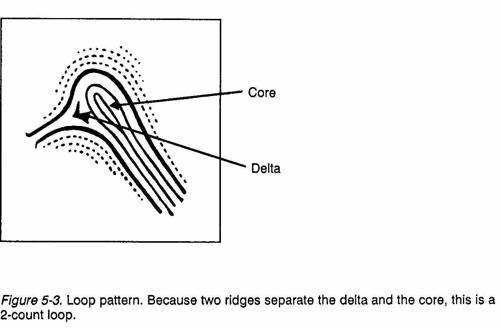

ulnar loop

would be listed according to its ridge count: 17, for example, if there are 17 ridges between the delta and the core.

A

radial loop

would be listed according to its ridge count plus 50; thus, a radial loop with 17 ridges between the delta and the core would be listed as 67.

An

arch

is shown as AA and a tented arch as TT.

Ten Arches and Bunny Feet

Remember that arches and tented arches together make up slightly less than 5 percent of all fingerprints; the proportion actually varies very slightly according to race from about 3.5 percent to about 6.5 percent. Arches and tented arches are most commonly found on the index and middle finger. Very few people have arches on all ten fingers; in fact, in Albany, as our total number of fingerprint cards rose from about 10,000 when I first began working with them to around 13,000 by the time I left, the number of all-arch cards remained constant. There were three. Two of them came from people I never met; the third came from Eddie.

Eddie was probably the stupidest burglar I ever met. Knowing from his first trial—assuming, of course, that he paid any attention to it—that he had the rarest ten-finger classification in the world, he went right on burglarizing, and he went right on not wearing gloves.

And Eddie had bunny feet. When law-enforcement people say somebody has bunny feet, they do not mean it as a compliment. A person who has—or grows—bunny feet is a person who has repeatedly escaped from custody.

Eddie burglarized a grocery store, eight doctors' offices, and several other businesses. We caught him. It wasn't too hard; all those arch patterns helped.

Eddie has another strange habit. When he's caught, he denies everything for about two minutes and then he starts to giggle and says, "Well, I guess you got me."

Eddie went to prison.

Eddie grew bunny feet. On his way home, burglarizing in every town he passed through on the way, he stopped and burglarized a sheriffs office in a nearby town.

We caught him. It wasn't too hard; all those arch patterns helped.

Eddie denied everything and then started giggling.

Eddie went to prison again, this time as a habitual offender. A few days later, I met a guard from the prison Eddie had been sent to the second time. I mentioned Eddie and his bunny feet. The guard thanked me for the warning.

I haven't seen Eddie since. But if I ever do, I'll recognize him easily. All those arches help.

Missing or amputated fingers are shown as XX, and patterns so scarred or mutilated that they are unreadable are shown as SR.

Figure 5-5 is a fingerprint card, already classified according to the simple Henry classification, not the FBI extensions. Following is the NCIC classification of that card:

WOTT0305TTDI06TT15TT That formula would allow any fingerprint technician to reconstruct the classification of the fingerprint card. But it would not allow identification.

Identification by Prints

And here's where we get into what fingerprinting is all about.

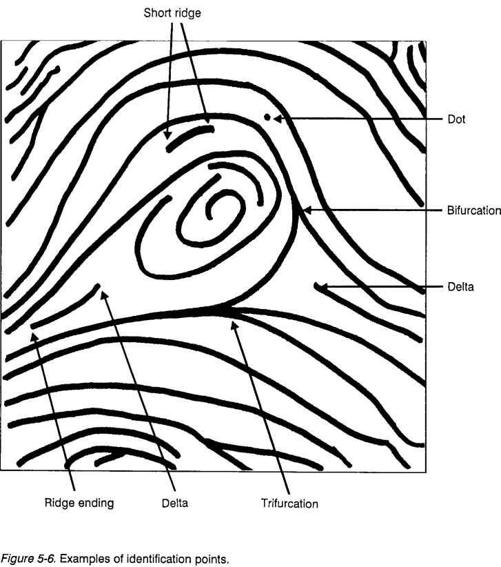

If fingerprints were composed entirely of straight or curved complete lines, identification would not be possible. But they are not. These lines stop and start, form islands. The main

minutiae—

identifying points—points of similarity, as identification technicians call them—of fingerprints are ridge endings, dots, short ridges, bifurcations and trifurcations (see Figure 5-6).

It is the arrangement of these identifying points that make identification possible. One of the individual fingerprints I succeeded in memorizing had a long, near-vertical triangle beginning at the delta, which formed the point of one of the angles. Toward the core, it had two long ridges followed by a short ridge. I did not have to memorize the entire print: These few details gave me five

points, and as I went through fingerprint cards every day, I could stop and compare any print I found that contained those five points. However, these five points were rare enough that in actual practice I have never seen another fingerprint, out of the hundreds of thousands of individual prints I have looked at, containing these points.

Which brings us to another common question.

Points of Similarity

How many points are required for certainty? Some countries have ruled on this; some of them require twenty-four points, which I consider an idiotic rule. To the best of my knowledge, no jurisdiction in the United States has set any standard. Very few technicians would be satisfied with fewer than eight points unless the points were extremely unusual; I will add that I once saw two prints that had seven points of similarity and that were not made by the same hand. A detective from another police department brought me the prints to look at, and it was only after he left that I realized I should have photographed the prints. I've wished ever since that I had, because that many points of similarity on nonidentical prints is extremely rare. In fact, as odd as this may seem, it is rare that there are any points of similarity on nonidentical prints, no matter how identical their classifications may be.

Determining a Thumbprint

Examine your thumbs carefully. You'll notice that at the top of your right thumb, the ridges tend to flow up and in toward the body. On the left thumb, the ridges at the top tend to flow up and in toward the body as well. This means that when the print happens to include the upper area, it is always possible to tell that it is a thumb, and which hand it belongs on.

The Most-Used Fingers

In burglaries and robberies, the fingers that most often show up are the index and middle fingers of the right hand, with the ring finger and the thumb running a close second and third. Remember, these are fingers 2 and 3 first, 1 and 4 second, according to the fingerprint numbering system. In forgeries, we get fingerprints far less often than we get palm prints — and you'll remember the discussion of palm prints in chapter four.

Among other things, all of this means that any time you have a thumbprint, or any time you have two fingers together, you can

always tell which hand was used. If you have just one finger and the print is of a loop, you can be almost certain which hand it is, because radial loops—loops sloping toward the thumb rather than toward the little finger—are rare, and they occur almost solely on the index finger. Therefore, you can make an educated guess as to whether the person who left the print was right-handed or left-handed. With whorls and only one finger, you are on less sure ground; with tented arches, you can rarely make more than a guess; and with plain arches, you'd really have to have at least the smudge of another finger to be sure which hand the print belongs on.

Can Fingerprints Be Forged?

When I first began fingerprint work, we were all assured that fingerprints could not be forged well enough to fool a good identification technician. That may still be true. But what most of us never considered was that a good, but dishonest, identification technician could forge a print and get away with it, as long as no other good identification technician studied his work. And we went on believing that until a case broke that made front pages across the country and was written up in

Reader's Digest.

The answer now is, yes, fingerprints can be forged. And at least one man went to prison on the basis of forged fingerprints.

Here is how the technician did it: First, he photocopied a known fingerprint of the suspect. Next, while the photocopy was still hot, he put fingerprint tape down on it and lifted the print. (This, of course, was perfectly easy to do; remember that powdered photocopier toner is used for fingerprint powder in some situations.) Then he put the tape down on the object he wanted to "find" the print on. And then he photographed the print, with the explanation—perfectly reasonable—that the tape had been put on the print to protect it.

The forgery finally was detected in the following manner: The suspected forgery was compared with all known prints of the onetime suspect, now victim. Although identification points are the same on all prints from the same finger, no two prints themselves should ever be identical, because of slight or great differences in position, pressure, and so forth. Therefore, when an inked print identical in every way to the purported latent was discovered, a strong presumption of forgery was created.

When the story broke in the media—when Doc was out of town and Butch not yet in ident—I knew every person in the police department was going to ask me questions about it. In order to forestall having to answer a hundred-and-eighty-odd different people, as soon as I read the article, I pulled my own fingerprint card out of the applicant file, photocopied it, lifted a print from it, taped it down on a lift card, typed an explanation under it, and put it on the bulletin board. It took me about five minutes, counting typing. That's how easy it was—and if the dishonest technician had destroyed the card he used to create the forgery, he might have gotten away with it.