Scene of the Crime (7 page)

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

items, there is no problem, because these items will be transported in boxes and there is no chance of the boxes' rubbing out prints.

Of course, with extremely large items, there may also be a problem, because it may be impossible to move the item without touching areas that might hold prints. In that case, it is essential to print the areas that must be touched, then move the item, and then finish the work in the lab. What if the item is outside and it's raining? Then you go crazy for a while. Honestly—I can't provide advice. You just assess the situation and try to do whatever will be least harmful to the evidence, then hope you haven't missed something vital.

For dramatic purposes, you may decide instead to have your character do whatever is

most

harmful to the evidence, either by accident, deliberately, or because the situation is so bad it cannot be redeemed.

Often, detectives brought us pieces of broken glass, holding them carefully by the edges, to have the surfaces printed. In a case like that, generally the detective would lay the glass on the seat beside him in the car on the way in, and hand it to us with a separate evidence tag for us to attach later. This worked well; the car's seat covers were too stiff to damage any prints, and it would take us only minutes to print the item and attach the tag.

This Glass is Full of—Something

Now suppose you need to fingerprint a container that is full of an unknown liquid. You will eventually have to get an analysis of the liquid, so you can't just dump it. You can't fingerprint the container with the liquid in it, because examining an item while fingerprinting it involves turning it in different directions to get the light on it at different angles.

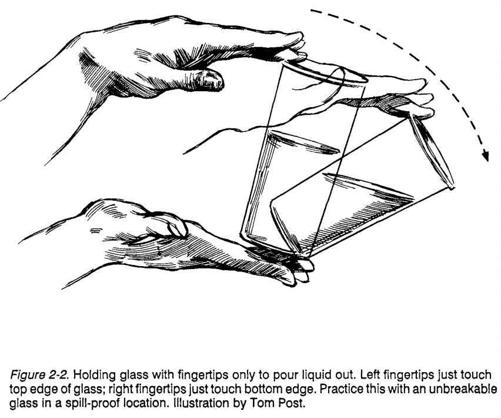

Being able to pick up a glass, cup or bottle by the rim and the angle where the side and the base join—using only your fingertips— and pour the contents into another container takes a lot of practice (see Figure 2-2). But that is the only way to do it. After that, the glass or cup must completely air dry before fingerprinting begins. (No, you should not use a hair dryer on it. The resultant heat and rapid moisture evaporation could harm any remaining fingerprints.) This in turn means that very often it must be transported into the police station with the dregs of the liquid still in it—which means that it must be packaged and transported right side up.

For collecting some evidence, -there are special kits you can

buy from suppliers or, sometimes, obtain from the crime lab. To collect blood samples in the preservative jar, simply unscrew the lid, collect the sample with the enclosed eyedropper, and screw the lid down again. The directions that come with the kit tell you which items do and do not need to be refrigerated. (After we got a refrigerator in the lab, many a day Doc, Butch and I stored our lunches in the same refrigerator that might be containing biological samples waiting to be transported to the lab. We were, of course, careful that everything—including lunches and samples—was properly packaged.)

A rape kit has to be kept refrigerated after use, and it should be transported to the lab as soon as possible. The officer or evidence technician does not personally use the rape kit; rather, s/he takes it to the hospital and turns it over to the examining physician, who will use the kit. (Preferably, the examination will be performed in the presence of a female officer, to cut down on the chain of evidence, unless the officer's presence is too distressing to the victim.) Following the examination, the physician turns the kit back over to the officer. The rape kit contains fine-toothed combs, tapes and vials to collect swabs from several pubic areas, vaginal washings and combings, and loose hairs that might be those of the suspect. These critical bits of evidence are the reason police ask the victim not to bathe until after she has been medically examined; very often the victim will then shower right in the hospital before putting on the fresh clothes she has taken with her. All the clothing she was wearing at the time of the assault and immediately after it will be turned over to the police in hopes that some hair, fiber and/or semen from the assailant remains on it.

Shoe Prints, Tire Tracks

Shoe prints and tire tracks are first photographed with a special camera on a frame that points directly down. Because the camera is on a frame, the ratio of the negative to the original (that is, the relationship in terms of size) is known, and the original track can be exactly reproduced in size. After that, the officer should make casts, often called moulages, of them. S/he begins by spraying the surface with a fixative; ordinary hair spray or shellac will do in a pinch, but a special fixative available from supply houses is preferable. Then a portable frame—metal or wood—is placed around the track. Using the bucket and stirring stick that is part of his/her equipment, and following package directions on the bag of plaster, the officer mixes the plaster with water obtained at the scene. (Someone who habitually goes places where water is not readily available should carry several gallons of water in the trunk of his/her car.) Very carefully, pouring onto the stirring stick held just above the print in order to break the flow and diffuse the plaster mixture and keep it from damaging the print, the officer pours the plaster into the frame. The plaster is reinforced with twigs, straw, and so forth from the scene; an officer who customarily goes places where s/he cannot expect to find twigs and straw should carry Popsicle sticks, available in bulk in craft stores under the name of "craft sticks," as a substitute. It is important to avoid using twigs and straw from a different location, as that might confuse scientists who are studying the shoes and tires and the casts.

Waiting for the plaster to dry may take anywhere from ten minutes to two hours, depending on the quality of the plaster and the atmospheric conditions. When it is nearly dry, a twig or even a finger is used as a stylus to put the officer's initials, the date and the case number in the back of the plaster. When it is completely dry, the casting is carefully lifted and put into a cardboard box upside down to finish drying. The officer should not try to clean it; that is left for the lab to do. This procedure accomplishes two things at once: it provides a cast of the shoe or tire, and it provides an exact sample of the soil, with its associated leaves, twigs and debris, in which the print was made, for comparison to the soil adhering to the shoe or tire.

Toolmarks

An officer should never attempt to fit a suspect tool into a toolmark; doing so would damage the evidence. If at all possible, the item the toolmark is on should be collected and packaged for transmittal to the lab. The crime-scene kit should contain a small saw, so that officers can, if necessary, saw out a section of the door frame where the pry mark is located. (I once moved into an apartment and noticed immediately that a section of an interior door frame had been sawed out and neatly painted over and several circles of carpet had been taken out and replaced with carpet almost, but not quite, matching in color. That alerted me that a major crime of some sort had occurred in that apartment.)

If removal of the area is absolutely impossible, dental casting material can be used to obtain an exact cast of the print. The officer must follow directions on the container, as there are many different types of dental casting material.

Fibers, Soil, Hair, Leaves, Pollen, Fireclay

Any piece of small evidence that is big enough to see, no matter what it is, should be collected with tweezers and put into coin envelopes (if there is the slightest possibility that it is even slightly damp) or into small plastic bags.

But what about the ones that are too small to see?

This is when an

evidence vacuum,

a small, extremely powerful vacuum cleaner equipped with filters, is useful. The vacuum cleaner is first cleaned, even if it is always cleaned after use,

just

in case somebody else forgot to do it last time. Then the officer inserts the first filter, and choosing a small, easily definable section, such as the floorboard, passenger's side, front seat, s/he vacuums up

everything

in that area. Then that filter with its entire contents is placed in an evidence bag, the vacuum cleaner is cleaned again, the second filter is inserted, and the work continues.

If the same area is going to be fingerprinted, it is essential to use the evidence vacuum before fingerprinting, to avoid contaminating the vacuum sweepings with fingerprint powder. Obviously, it takes something of a contortionist to vacuum an area without touching it, but ident people learn to do such things.

Soil and Leaf Samples Outdoors

Samples are collected from every area the perp would have contacted. Each one is packaged separately; both the evidence tag and the officer's notes should tell

exactly

where each sample came from. Triangulation is crucial in case someone else should have to locate the exact same spot again.

Broken Glass

You already know how glass is collected without damaging fingerprints. Your officer will be sure to identify, in notes and on the evidence tag, exactly where each fragment came from. The lab needs that information.

Blood Spatters

Blood spatters can be few and widely scattered; they can be widely dispersed over a large area. Totally accurate photography and measurements are critical. In a case in Cincinnati, a man was stabbed in the lung. Blood in the lung mixed with the air and sprayed through the exit wound, so that a fine, almost imperceptible mist of blood covered the immediate area. Detectives observed that an area of floor was

not

sprayed; from that they were able to ascertain the shape of the perp's jacket, and to deduce that when they found the perp's jacket, it would have blood on it. In other cases —these involving stabbing or bashing—detectives have been able to determine from the pattern of blood spattering the height and even the hand preference of the perp, and —again—to know that certain items of clothing will have blood on them.

Not all blood is red; not all blood tracings are visible. Large amounts of blood, after being exposed to air for several hours, turn to a very glossy black and tend to dry in stacks and then crack, so that the floor will appear to be covered by irregular stacks of glossy black tile. In other situations, blood may turn pinkish, brownish or even greenish. It is very difficult to scrub all the blood up; even after the walls and floors appear immaculate to the naked eye, spraying the area with a chemical called luminol (which is available in several different trademarked packagings) will cause all areas where blood has been to fluoresce. In such a case, taking up the floorboards, tile or carpet will usually disclose puddles of blood lying on the subflooring. It may also be necessary to take apart the plumbing and look for blood traces in the sink traps.

Smaller spatters of blood should be allowed to dry naturally, even if that involves keeping the scene sealed and guarded for several days. Then each one should be measured, rephotographed, traced in complete detail and carefully triangulated not only in location, but also in exact position within that location (is the spray coming from up or down, left or right?). Then, if possible, the surface containing the spatters should be removed to the lab.

What can the lab do with the spatters? We'll get to all that later, in chapter nine, which tells what the lab does, and in the appendices, which provide sample lab reports.

Let's go on, now, to firearms. They deserve a section all their

own.

TABLE 2

_

Processing the Crime Scene

These pages come from the

Evidence Collection Manual,

published by Sirchie Finger Print Laboratories, Inc., and are used by permission. The charts have been edited for use in this publication.

The following is a brief procedural guideline for collecting and preserving physical evidence at the scene of a crime. Any number of commercially available journals provide excellent detailed information regarding the science of evidence collection. We strongly recommend our Sirchie TB300,

Evidence Collection Mission,

as an outstanding source of detailed information.

Clear the area:

Clear all except essential and authorized persons from the crime-scene area. This includes all officers who are not needed for specific functions. The more people present, the more chance for damage or loss of evidence.

Use a systematic approach:

Use caution when searching for evidence. Study the whole crime-scene area first, since the relationship of different exhibit positions may be important. Systematically cover the crime scene so that nonobvious or hidden evidence is not overlooked. Speed and carelessness may lead to overlooking evidence or to the damage or destruction of important exhibits.