Scene of the Crime (4 page)

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

Photographing the Scene

This time we can't let the corpse be moved yet—not that anybody really wants to move it anyway. The first thing we're going to do now is take photographs. Look ahead at Figure 1-2 for just a minute. Imagine yourself standing just inside the front—south— door. Check your camera for the number of the next exposure. Now take a picture pointing the camera just to the left, getting a little view of the kitchen. Stop

immediately

and make a note telling what this exposure showed, as well as what kind of film and what f-stop you used. If you work with different cameras at different times, you

might even note what camera you were using. Your note might look like this:

Roll 1. Exposure 8. 816 North Jackson. Int. kitchen taken from front door. Minolta 35mm SRT-100 w/50mm lens. Kodak Tri-X Pan ASA 400 27 DIN. f-16 @ 1/60 sec. with strobe.

I was still using black-and-white film in those days. Now, of course, crime scenes are photographed in color except in the very smallest and poorest departments. But—in real life — a police officer or private investigator will know what kind of film s/he is using. There's more about cameras and film in chapter nine.

If you know enough about photography to know what most of the information I gave means, you'll also want to know that in general, you'll be going for the greatest depth of field possible. The few exceptions occur when you are taking close-up photos of small items, wounds, weapons, fingerprints, footprints, and so forth. Then you'll probably be wanting to home in on the important feature and blur out just about everything else.

If things like ASA and DIN and f-stops don't mean anything to you, either read a good camera book or forget about them. You don't necessarily need them to write mysteries.

A lot more information than anybody reasonably should want? Sure it is—but who ever said defense attorneys were reasonable? If you don't have all that information, sooner or later some attorney is going to say, reproachfully, "Now, Officer So-and-So, tell the truth. Did you actually take these photographs?"

Of course you don't have to repeat all the information in every note, if you're taking photos in a sequence. Here's how your next couple of notes might look:

Exposure 9. 816 North Jackson. Int. kitchen, part of table, taken from front door.

Exposure 10. 816 North Jackson. Part of table, part of west wall, part of bathroom door, taken from front door.

This is assuming the rest of the information has not changed. When it does, your note will look like this:

Roll 2. Exposure 4. 816 North Jackson. Exterior, north wall taken from back property line, f-22 1/200 sec. without strobe.

The assumption here is that you are still using the same camera

and lens and, although you have changed rolls, you are still using the same

type

of film.

When you write your report, all this information will be included. Nit-picking? Sure it is. But in real life, there is too much at stake to take chances. In fiction, play it however you want to, for whatever your reasons are. Certainly very little of this information will actually turn up in any given story or novel—but it's useful to know what you can do with it if the information is recorded incorrectly.

Pan—that means rotate—the camera a little to the right, but stop when you still overlap the first shot. Take a second photograph and make all your notes again. When you've shot all the way around the room—which might take eight to twelve

overlapping

photographs—walk

directly

across the room, so that you're facing your original position, and take a picture of it. In a larger house you will need to do this in

each

room that could be related to the crime.

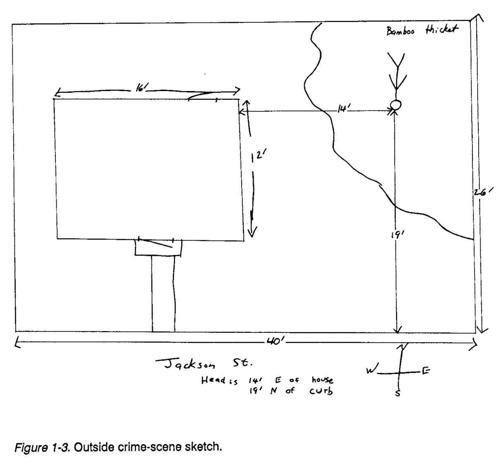

Now you'll take the camera outside (see Figure 1-3). Take one photograph each from the north, the south, the east, and the west of the house itself, and one each from the north, the south, the east, and the west of the bamboo thicket—or whatever you have in your crime scene.

As in this case it appears likely that the victim was carried out the back door into the bamboo thicket, take pictures of the back door from inside and from outside. Then, from the back door, take a picture of the bamboo thicket. Walk toward the bamboo thicket, taking pictures at about two-foot intervals. When you have reached the body, take at least one photograph each from left, from right, from top, from bottom, and from above, looking directly down.

In this case there is nothing unusual about the body you need to photograph now. If there were bullet or stab wounds, or defense wounds (we'll get to that later), you'd photograph them now.

Sketch and Measure

Next we have to take measurements and make sketches, both inside and outside. For the moment—look, we too like to breathe once in a while—we'll go inside, where the air is a little better.

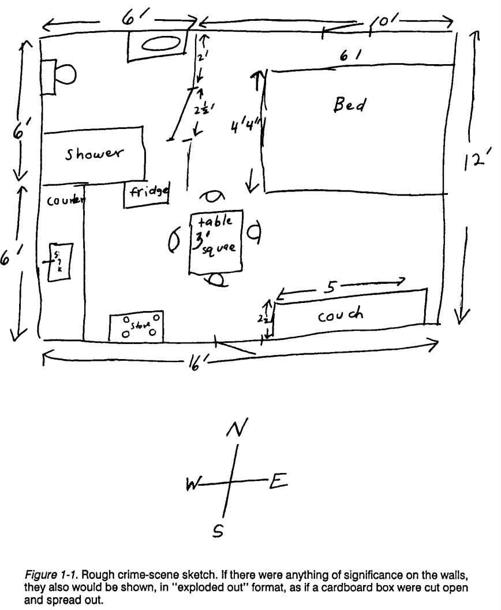

We'll begin with a rough sketch (see Figure 1-1), getting in all the measurements so that we can make a finished drawing later for court if the case goes to court. To take the measurements, put you at one end of the tape measure and Mel (remember Mel, your part-

ner?) at the other end of the tape measure. If you must do it by yourself, you can step it off—learn the length of your normal stride—but that is far from ideal.

As you can tell, it is very rough indeed; in fact, not all of it is fully legible. (That word that meant to be

stove

might just as well be

shave.)

But that's okay, because this drawing goes in your notebook, your case file. You'll make a better drawing later for the D.A. to see. You'll do that one sitting at your desk, using things like rulers, compasses, protractors—yep, those same things you learned how to use in the seventh grade, and weren't they fun?

In some larger police departments, they've even gone over to using computers to make crime-scene drawings. I never worked on a department that big, and chances are your fictional detective—if s/he's a cop at all—doesn't either. But if you're writing about New York or Los Angeles or Chicago, or their environs, you might want to call and be sure.

You may be thinking, now, that you don't need to make these drawings, because you're not working a real crime; you're writing a book.

Oh, yeah?

I've found that if I don't make a realistic drawing of every one of my fictional crime scenes, I wind up forgetting where things are, which direction doors open, and even where the body was. While I'm about it, I make maps of every location I made up, and get out maps of every real place I'm talking about. It's easy—and sloppy— to say it doesn't matter that much, it's only fiction. And it may be true that no more than one reader out of a thousand will catch you on the errors. But you'll know the difference. Martin Cruz Smith, who began as a mystery writer, says to writers' groups that integrity in writing is critical, and if you don't have it, you'll know it, and your work will show it.

Giving your fictional crime scene the care you'd give a real one is one way to maintain that integrity.

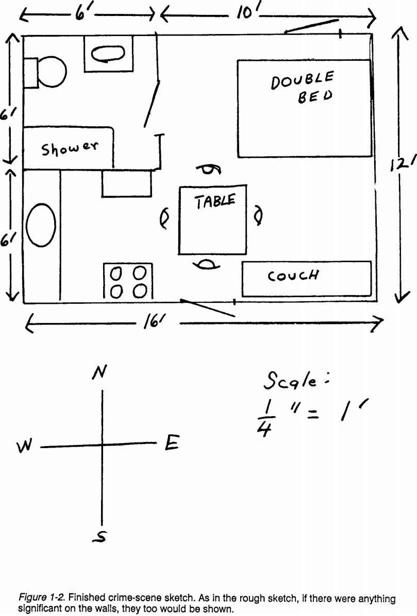

The final sketch (see Figure 1-2) is still not terrific, but that's okay. This is as good as it needs to be, most of the time. If you get Melvin Belli as a defense attorney you might want a much better drawing, but in that case you might have to ask a professional artist to do it. Most detectives—public sector or private —aren't extremely good at art.

In some cases, nothing outside is of immense importance. How-

ever, in this case, although the killing almost certainly took place indoors, the body was found outside. That means measurements and a sketch of the exterior also are necessary (see Figure 1-3).

Notice that the position of the body is

triangulated—

that is, measured from two fixed points, so that its location can be described absolutely accurately.

Now, you've got all the photographs and all the sketches and measurements you need to start with. Tell the EMT's they can move the body.

What do you mean they'd just as soon not? Do they expect it to stay here till next January? Hey, fellas, come and take it away.

Now.

It's gone. The place doesn't smell appreciably better.

TABLE I

_

Who Does What When?

Dispatch—

• Receives initial telephoned complaint.

• Responds calmly to emergency situations.

• Provides help as possible over the phone.

• Sends patrol units and other essential personnel to scene.

• Receives reports from patrol units.

• Sends additional personnel to scene as need is reported.

• Coordinates car chases or foot chases, keeping units advised of each other's situation and location at all times.

• Maintains log of all calls.

• Retains tape recordings of all significant matters until they are disposed of.

• Knows whereabouts of all officers at all times.

• Prepares and dispatches updated lookout bulletins.

• On officers' requests, checks National Crime Information Center and other computerized data bases for wants and other information.

• As necessary, coordinates own department's efforts with efforts of other departments.

• Testifies in court as necessary. Patrol Division—

• Gets the initial call.

• Goes to the scene and determines the situation.

• Gets initial information from complainant.

• Asks dispatch to send whoever else is needed.

• Contains witnesses.

• Controls scene.

• Makes arrest if perp is immediately visible.

• Chases perp if perp is attempting to escape.

• Assists detectives when they arrive.

• Makes initial report.

• Testifies in court as needed. Detective Division—

• Goes to scene of major crimes.

• Asks dispatch to send whoever else is needed that patrol has not sent for.

• Interviews witnesses at scene.

• Instructs patrol division in more ways to help.

• Canvasses area to look for more possible witnesses.

• Arranges transport for witnesses to headquarters.

• Takes written statements from witnesses.