Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 (5 page)

Read Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 Online

Authors: Damien Broderick,Paul di Filippo

Can the generous, communal way of life in the Valley speak to us? An Archival message cited by Stone Telling suggests it might:

In leaving progress to the machines, in letting technology go forward on its own terms and selecting from it… is it possible that in thus opting not to move “forward” or not only “forward,” these people did in fact succeed in living in human history, with energy, liberty, and grace?

[1]

In

Dancing at the Edge of the World,

London: Gollancz, 1989, pp. 169-70.

5

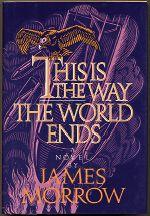

James Morrow

(1985)

PLANNING THERMONUCLEAR WAR

and its aftermath, Mutually Assured Destruction, used to be called, euphemistically but chillingly, “thinking about the unthinkable.” Science fiction has often thought about the unthinkable, all too often with unthinkable relish. By contrast,

This is the Way the World Ends

is like a punch in the mouth by the Angel of Death in the garb of a stand-up comic. It was quickly compared to Jonathan Schell (

The Fate of the Earth

)

out of Kurt Vonnegut, which was spot-on. It is likely, however, that the careful study by Schell, in the 1980s a prominent opponent of nuclear arms race strategy, is already forgotten, even as more nations than ever around the globe arm themselves with nuclear weapons, and plan resource-crisis wars.

George Paxton is a tomb cutter with an “adorable daughter” and a wife “who always looked as if she had just come from doing something dangerous and lewd.” He has been spared misery: “the coin of George Paxton’s life had happiness stamped on both sides—no despair for George. Individuals so fortunate were scarce in those days. You could have sold tickets” to his life. His neighbor sells

scopas

suits, for Self-Contained Post-Attack Survival, and Paxton buys one, signing a meaningless document admitting his complicity in any subsequent nuclear exchange.

In the dreadful event, the suits do not work, any more than the schoolroom “duck and cover” drills of the 1950s would have done. Here is part of Chapter 5, “In Which the Limitations of Civil Defense Are Explicated in a Manner Some Readers May Find Distressing”:

Townspeople marched down to the river... arms outstretched to lessen the weight of their burned hands. Many lacked hair and eyelashes... A white lava of melted eye tissue dripped from their heads; they appeared to be crying their own eyes.

A seeing-eye dog, its scopas suit and fur seared away, licked the face of its dead master. “Somebody put the fur back on that dog!” George shouted.

It is not sentimentality to be moved profoundly by these images of carnage and horror. Nor is it ghoulish to laugh with Morrow at the black, bleak post-holocaust progress of George Paxton, his good-hearted Candide. Twenty-five years on, long after the collapse of one wing of this appalling calculus of global death, the twenty-first century might not be the worst of times. But neither is it yet the best of times, for international terrorism, the forces underpinning its threat, and massive military responses to it, ensure that George’s world might yet ignite around us. Morrow’s splendid novel, only in unimportant ways superannuated by political shifts, lives on.

Morrow’s conceit in this grimly satirical novel is that those complicit in the suicide of the human race might be held accountable in war trials conducted in Antarctica by the Unadmitted—those immense multitudes who are doomed to non-existence by this universal, self-inflicted cataclysm. It is a hazardous device for a moralist like Morrow, because it seems to open out into all kinds of other metaphysical trials, not least of all those involved in the use of contraception to limit family size, or of abortion. The distinction, though, is that Morrow’s apocalypse destroys existing persons—adults and children—as well as “potential” human beings.

In this Tribunal of the Unadmitted, representatives of the final holocaust stand accused. They are politicians, arms merchants, apologists for war, a hypocrite meant to implement arms control “who never in his entire career denied the Pentagon a system it really wanted.” Among these patently guilty stands sweet-natured George Paxton, Morrow’s Everyman: “citizen, perhaps the most guilty of all. Every night, this man went to bed knowing that the human race was pointing nuclear weapons at itself. Every morning, he woke up knowing that the weapons were still there. And yet he never took a single step to relieve the threat.”

Can George truly be found guilty, in this Swiftian drama? Isn’t the horrendous violence of the novel, foreseen with darkly comic irony by Morrow’s version of Nostradamus, just a side-effect of our evolutionary past? Thomas Aquinas, for the prosecution, will not allow this plea to go unchallenged:

“Are we innately aggressive?” asked Aquinas. “Was the nuclear predicament symptomatic of a more profound depravity? Nobody knows. But if this is so—and I suspect that it is—then the responsibility for what we are pleased to call our inhumanity still rests squarely in our blood-soaked hands… And then, one cold Christmas season, death came to an admirable species—a species that wrote symphonies and sired Leonardo da Vinci and would have gone to the stars. It did not have to be this way. Three virtues only were needed—creative diplomacy, technical ingenuity, and moral outrage. But the greatest of these is moral outrage.”

Morrow’s own moral outrage is evident, and powerfully expressed. Not all readers will agree. They are given their spokesmen: “Self-righteous slop, you needed that too,” replied one of the accused. But Morrow does not leave the verdict open. George, unlike the rest, avoids the counts of Crimes Against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes Against Humanity. But the court finds him unequivocally guilty of Crimes Against the Future, and sentenced him to be hanged.

What makes this novel more than a one-sided pamphlet by a pacifist is its nuance, its attention to the detail of real life in the midst of its phantasmagorical, almost Lewis Carrollian trading of accusation and defense. Escaping, fleeing across ice on a giant prehistoric vulture, he meets his beloved daughter:

“Honey, there’s something I want to ask.”

“What?’

“Do you know what’s happened to you?”

“Yes, I know.”

“What’s happened to you?”

“I don’t want to tell you.”

“Please tell me.”

“You

know

what’s happened.”

“Tell me.”

“I died.”

This is not a light-hearted or thrilling entertainment of a novel. But it is a necessary one, still.

6

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

(1985)

SENTIMENTAL

, cynical, clear-eyed, spiritual, godless, often very funny, Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007) was more than a cult favorite in the 1960s and ’70s but has fallen from popular favor. His early novel

The Sirens of Titan

was unabashed paperback sf, but of a kind rarely seen until then, and

Cat’s Cradle

was almost as explicitly science fictional. Many of his subsequent novels contain an uncanny quality, verging on sf without ever quite going there.

Galápagos

tells the cautionary and scathing tale of humanity’s future evolution into mindlessness, narrated by a ghost still lingering a million years hence. That ghost, as it happens, is Leon Trotsky Trout, son of the prolific Kilgore Trout whose terrible sf is quoted through most of Vonnegut’s fiction after his appearance in

Breakfast of Champions

(1973). It’s obvious that Trout is a fond if mocking mask for sf master Theodore Sturgeon, but really he is, of course, Vonnegut himself. As, too, is Leon, who recalls humankind’s ruined world, brought down (he asserts) by the excesses of our huge, intelligent, obsessive and endlessly tricked and tricky three-pound brain.

Perhaps the oddest aspect of this bittersweet fable, told by an apparent anti-intellectual misanthrope hanging onto hope by the skin of his teeth, is how startlingly accurate his near-future predictions were. Global financial collapse is due to “a sudden revision of human opinions as to the value of money and stocks and bonds and mortgages and so on, bits of paper,” wealth “wholly imaginary… weightless and impalpable,” just as it nearly did a quarter century later.

A Japanese genius invents the Mandarax, a handheld device in “high-impact black plastic, twelve centimeters high, eight wide, and two thick,” with a screen the size of a playing card, that can translate a thousand languages, diagnose illnesses, bring up any kind of information or literary quote. At a time when “portable” or luggable computers were known as boat anchors and linked by phone lines, Vonnegut had foreseen Google and the iPhone (which, to draw on the kind of absurdist detail he peppers his pages with, is 11.6 by 6.2 by 1.2 cm). All of this information is useless after the Fall, Trout claims, and dubs the Mandarax “the Apple of Knowledge.” A nod to Genesis, but a startling and amusing intimation of the Apple iPhone…

The Galápagos islands, described with distaste in 1832 by Charles Darwin as a “broken field of black basaltic lava, thrown into the most rugged waves, and crossed by great fissures, is everywhere covered by stunted, sun-burnt brushwood, which shows little signs of life,” become the home of the last traditional humans, one man and nine women.

From this remnant, marooned on Santa Rosalia, home of the vampire finch, springs the non-sapient

Homo sapiens

of the next million years. Eventually our descendants are aquatic fish-eaters with a head sleek and narrow, jaws adapted to snatching their marine prey, skull too cramped for intelligent thought. To Trout, this is a satisfactory consummation; the fittest have survived, even if their initial “fitness” was sheer dumb accident in a world smashed by human ingenuity and an infertility virus (perhaps inspired by AIDS) spread through the machineries of world-girdling technology. The Galápagos are spared precisely by their isolation. The new humans are inbred, furred because of a mutation engendered in a Japanese child by her mother’s exposure to the Hiroshima bombing, but at least spared the heritable Huntington’s chorea (ironically, a mind-destroying illness) that their ship’s Captain fears he carries. It is a future of “utter hopelessness.”

Vonnegut being the kind of Mark Twain writer he was, all of this hopelessness is screamingly funny.

In a typographical stunt that blends foreboding with a cheeky grin, all those fated to die before next sunset are given an asterisk before their name. *Andrew MacIntosh is a sociopath billionaire with a blind daughter, Selena, who survives. Her seeing-eye bitch is Kazakh, who, “thanks to surgery and training, had virtually no personality”—like the posthumans of the far future, who manage it by natural selection. (Curiously, Kazak without an h is the alert canine companion to Winston Niles Rumfoord in

Sirens of Titan,

whose fate is to become detached in time and space. This probably signifies the sort of meaningless coincidence that for Vonnegut comprises most of the events of life and indeed the universe.) *Zenji Hiroguchi is the inventor of the Mandarax, and his death strands his pregnant wife Hisako, skilled in ikebana or flower arrangement, in a hellish landscape devoid of flowers.

Adolf von Kleist avoids Huntington’s (unlike his brother *Siegfried). He is captain of the

Bahía de Darwin,

out of Ecuador, deserted by its crew. This vessel is chosen for “the Nature Cruise of the Century,” a strenuously promoted event that attracts celebrities such as Jacky Onassis and Rudolph Nureyev, although both are spared the rigors of Santa Rosalia as the human world goes bankrupt and sterile. This ship of fools comprises rogues, victims and other hapless souls: fiftyish Mary Hepburn in surplus combat fatigues, widowed school teacher; *James Wait, a younger swindler who makes Mary his eighteenth wife; Jesús

Ortiz, an Inca waiter who idolizes the wealthy and hopes to join their number until a brutal encounter with financier *MacIntosh sets him straight; others. Leon Trout, political refugee to Sweden from the Vietnam War after partaking in a My Lai-type massacre, is not aboard, being dead, but we learn his tale as well, and that of six little Kanka-bono cannibal girls.