Secret Journey to Planet Serpo (7 page)

A RETURN VISIT

During that five-year period, which constituted the final years of the Eisenhower administration, the scientists continued to seek to arrange a return visit of the Ebens to Earth. Apparently, the desire for another visit was mutual. It appeared that we both wanted to establish some sort of diplomatic relationship. As previously mentioned, while weâespecially our scientistsâwere no doubt motivated by high-minded sociological and scientific interests, our government officials and military and intelligence people were suspicious of the aliens' intentions, and were more concerned with understanding their advanced technology, particularly as it applied to weaponry. We were probably still hopeful that a return visit would lead to an exchange program. It will be recalled that this was proposed by Ebe1 in his fifth message, at our prompting, but if he did receive a reply agreeing to this, he wasn't able to translate it for us. Very probably, the aliens had the same goals. We can safely conclude that they were very much interested in our atomic bombs. As we later learned while on their planet, they had not developed atomic energy, although they did have the more powerful particle-beam weaponry, and had used it in war.

Furthermore, the Ebens wanted to retrieve the bodies of their dead comrades. This involved some complications. While we did keep the remains of the bodies frozen at Los Alamos, using some very advanced cryonic technology, Anonymous says that we performed autopsies on four of the five dead aliens found at the Corona crash site. This was probably explained to them, but should not have surprised or shocked them at all. In fact, they probably expected it, and, as we later learned on Serpo, the Ebens had a rather ghoulish biotechnology research operation of their own that went far beyond simple autopsies.

Planning the return visit turned out to be much more complicated than we had expected. We were unable to understand their date and time system, and they could not comprehend ours. We sent them all the details of our planetary rotation and revolution, how we marked dates and time, and precisely where we were at the moment we sent the data. But the Ebens were never able to understand our system. Finally, by 1960, we figured out theirs, and we were able to send them longitude and latitude coordinates that we thought they could understand; however, we couldn't be sure. In early 1962 we developed a better arrangement. Anonymous says, “We then decided to just send pictures showing the Earth, landmarks, and a simple numbering system for time periods.” They allowed us to select a date, and we chose April 24, 1964. Selecting a landing location proved to be even more complex. The military planners wanted to make absolutely certain that security would not be compromised, and that the press or the public would not even get a hint of what was going on. At first they considered remote islands, but then realized that unusual movements of naval vessels could arouse suspicion. They decided that the site had to be controlled by the military to ensure complete secrecy. Finally, they settled on the southern end of the White Sands Missile Range, near Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. Holloman was previously known as Alamogordo Army Air Field, a training site for Eighth Air Force bombardment crews during World War II. They also selected a fake location on the base itself to misdirect interest. These decisions were made, and confirmed by the Ebens, in March 1962. It had taken ten years from the time of the death of Ebe1 to arrive at this historic agreement.

AN INCOMPLETE STORY

This long-range planning schedule is somewhat surprising, since the Ebens must have had a mother ship already in orbit around Earth, and consequently must have been able to send scout ships to the surface without delay. Certainly, that tiny six-man craft that crashed near Roswell did not travel to Earth by itself over thirty-eight light-years from the Zeta Reticuli system, which we later determined to be their home constellation. And if a mother ship had remained in orbit around our planet after the Roswell crash, why was it not possible for the Ebens to just send another scout craft to the surface to arrange the formal rendezvous directly? Certainly, MJ-12 and the government must have wondered about that and must have asked that question over the communication device at an early stage in the interplanetary dialogue.

This brings up the possibility that this did indeed happenâthat some negotiations may have ensued without the subsequent knowledge of the DIA, the agency that ultimately released the Serpo material in 2005. This should come as no surprise, since the DIA did not exist in 1953. The Defense Intelligence Agency was created by President John F. Kennedy's secretary of defense, Robert S. McNamara, in October 1961. Consequently, whatever happened between the Roswell crash in July 1947 and the advent of the DIA in 1961 could only have been known to them from information they were able to gather after their creation, from top secret Army and Air Force intelligence sources operating under President Eisenhower. And it would be fair to conclude that these military intelligence agencies were not very happy about having to turn this information over to a brand-new intelligence agency created by a new, young, Democratic president, who planned to replace them by combining all their functions under a single umbrella organization. Consequently, they were probably not very cooperative, and may have provided incomplete information, or possibly even disinformation, about the era when Eisenhower was president. Most likely, they convinced MJ-12 itself not to share that intelligence with the DIA in the interests of compartmentalization. As will be seen in chapter 5, this is probably exactly what happened, since we now know that the Ebens did send another scout craft to Earth on May 20, 1953. And that craft did not crashâit landed. Evidently, those messages that were sent in early 1953 must have been answered after all, but the DIA was not informed about this when the agency joined the project in 1962.

5

KINGMAN

Just as with the Roswell story, the revelation that an alien craft was thought to have crashed near Kingman, Arizona, in 1953 was kept tightly contained for almost twenty-five years. And, if it hadn't been for the very thorough reporting of a dedicated NICAP (National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena) investigator, it probably would have remained buried for at least another ten years. The dogged and indomitable digging of the NICAP UFO teams in the 1950s and 1960s, and their rigid screening and reporting protocols, have become legendary. Time and again, their facts were proven incontrovertible, and their reports were unassailable. And it was this professionalism that most impressed the newspapers, and convinced them to give the UFO story mainstream coverage in the 1960s. As a result of that publicity, the government was embarrassed into forming its own formal public UFO investigative organization in 1966âthe now-infamous Condon Committee, which relied heavily on the fieldwork and reports of NICAP. Author and veteran NICAP investigator Raymond E. Fowler first broke the Kingman story in an article in

UFO Magazine

in 1976. This article was then incorporated into his book,

Casebook of a UFO Investigator: A Personal Memoir,

published by Prentice-Hall in March 1981. J. Allen Hynek, the chief scientific consultant for the Air Force Project Bluebook, said about Fowler “an outstanding UFO investigator . . . I know of no one who is more dedicated, trustworthy or persevering. . . . [Fowler's] meticulous and detailed investigations . . . far exceed the investigations of Bluebook” (

www.crowdedskies.com/ray_fowler_bio.htm

).

UFO investigator Raymond E. Fowler

In his article (and in his book), Fowler reports that, in the course of his NICAP investigations in 1973, he interviewed someone regarding a crashed disc found in Arizona. The interviewee chose to remain anonymous in Fowler's report, but agreed to go by the assumed name Fritz Werner. Always thorough in obtaining evidence, Fowler asked Werner for a signed statement giving all the details of his experience, which he agreed to. In that statement, dated June 7, 1973, Werner testified that on May 21, 1953, he “assisted in the investigation of a crashed unknown object in the vicinity of Kingman, Arizona” (see

plate 6

). In the statement, Werner described the object as oval, and about thirty feet in diameter. He said it was constructed of “an unfamiliar metal which resembled brushed aluminum.” He said further that the disc was undamaged, and had penetrated only about twenty inches into the sand. This would suggest that it came down at a very moderate speed, implying that perhaps this really wasn't a crash at all, but more of a landing. A hatch about 3½ feet high was open, another indication of an orderly landing and egress. The hatch height suggested that the occupants of the craft were about that tall. As part of his statement, Werner claimed that he saw a dead alien in a tent near the craft. In his own words, as reported by Fowler, he said, “An armed military policeman guarded a tent pitched nearby. I managed to glance inside at one point, and saw the dead body of a four-foot human-like creature in a silver metallic-looking suit. The skin on its face was dark brown.” His testimony becomes slightly questionable at this point because, in his description, he stated with confidence that this alien had been the “only occupant.” Since he was not permitted to enter the craft, there was no way he could have known by observation how many occupants had been inside. Consequently, somebody in authority must have told him that. This “slip” opens the entire statement up to the possibility of disinformation. It suggests that he was deliberately allowed to notice the dead alien, and then was told that it was the only occupant.

Werner told Fowler that he was one of about fifteen engineers and scientists brought to the crash site in a bus with blackened windows from Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport, on the night of May 21, 1953. He had been working on loan to the Atomic Energy Commission at the Nevada Test Site to assess the damage to various structures due to atomic test blasts. He was flown into Sky Harbor from the Indian Springs, Nevada, Air Force Base. At the Kingman site, given his particular expertise, he was expected to estimate the velocity of the disc at impact from the way it was embedded in the soil. He ultimately concluded that it had been traveling at about 100 knots (115 mph). That could almost be considered landing speed for an antigravity craft. Fowler knew Werner's real name, which we now know is Arthur G. Stancil, and did check him out meticulously. He found that in 1953 Stancil was indeed a project engineer with the Air Force under contract to the Atomic Energy Commission. He had previously worked at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in the Foreign Technology Division. He determined that Stancil's history and all his credentials were genuine, and that he had no reason to try to perpetrate a hoax.

Each of the people on the bus was escorted one at a time, by military policemen from the bus to the heavily guarded, brightly illuminated site, and instructed to just focus on his or her specific job. And they were told not to engage in any fraternization or discussion about what they learned. So really Werner was violating the instructions when he peered inside the tent. Given the rigid security measures governing the entire procedure, it is highly unlikely that the MPs failed to prevent Werner from looking into the tent. More likely, he was allowed to see the alien, and to go away believing that he had stolen a furtive glance, and was then led to believe that he had seen the only occupant, and that occupant was dead. In fact, it seems unlikely that this staged scene was only for Werner's benefit. Very probably, all fifteen investigators had the same opportunity.

And when it came to secrecy vows, all the participants received very lightweight treatment. An Air Force colonel got on the bus and had them all sign the Official Secrets Act. He then asked them all to raise their right hand and take an oath to never reveal what they had experienced. This was very different from the horror stories others have talked about, where terrifying intimidation and death threats were common. It seems likely that the Air Force expected and wanted these people to later reveal the event and what they had seen in the tent so that the “sole dead occupant” version would gain currency. We will see below why this tricky bit of manipulation might have been carried out, and why it was so important.

A DIFFERENT VERSION

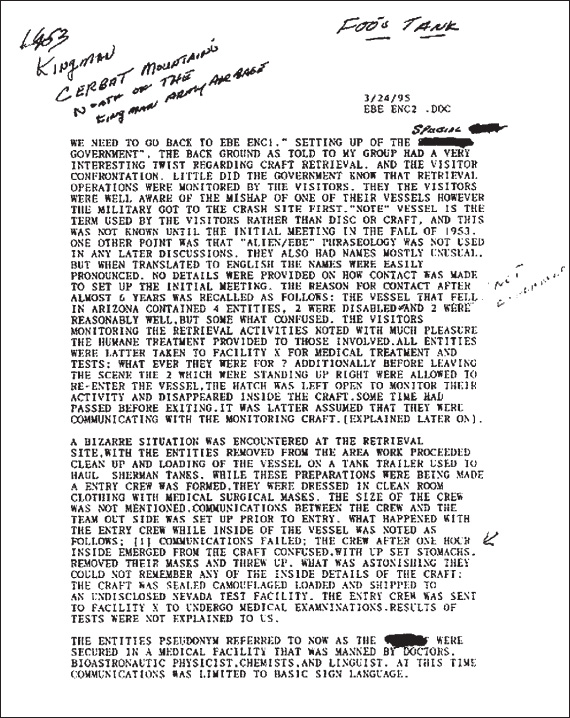

The website that hosted the original Project Serpo revelation,

www.serpo.org

, invited military, intelligence, and other government insiders who had direct knowledge about the Serpo story to send in what they knew, or had experienced, for publication on the website. One such contribution published on the site in August 2006 sheds new light on what actually happened at Kingman. It is a photographic image of a two-page classified memo, evidently written as a briefing document for another government group. It is dated March 24, 1995. It's interesting to note here that whoever sent it in evidently understood, or perhaps suspected, that there was a connection between the Kingman event and Project Serpo. It was sent by a researcher who supplied his name, but remained unidentified in the posting. In the typed copy, the document makes reference to a “vessel that fell in Arizona.” Written in longhand, at the top it says, “1953 Kingman Cerbat Mountains north of the Kingman Army Air Base.” The Army air base is now the Kingman Municipal Airport. The Cerbat Mountains are about ten miles northwest of the airport.

The document gives fascinating insider details about the Kingman crash retrieval as part of an explanation of how the long-term relationship with the Ebens developed, and how the reverse-engineering program began. To begin with, it is a confirmation of Stancil's report that an alien craft came down near Kingman in 1953. The major departure from his report concerns the number of occupants and their condition. The document says that there were four, all alive, claiming “The vessel . . . contained 4 entities, 2 were disabled and 2 were reasonably well, but some what [sic] confused.” The writer of this document claims to know that another alien craft was actively monitoring the craft retrieval, although our people were not aware of that at the time. He says, “Little did the government know that the retrieval operations were monitored by the visitors . . . the visitors were well aware of the mishap of one of their vessels, however the military got to the crash site first.” The choice of the word “mishap” is very interesting in this context. It infers that the problem was not so much that the craft crashed, but that the landing place was not the intended location. It implies that the craft missed its destination. Considering that the retrieved disc was ultimately taken to the Nevada Test Site, it is reasonable to conclude that it was originally heading for that location, only about two hundred miles away on a direct northwest flight path.

Memo sent to the Project Serpo website

Cerbat Mountains near Kingman, Arizona

Â

The likelihood that this rendezvous was prearranged explains why the military retrieval crew got there so quickly. The over-the-road military response had to be lightning-fast in order to be ahead of the supersonic alien craft. Evidently, the retrieval team had been on alert throughout the Arizona-Nevada area, anticipating that just such a “mishap” might occur. What is most amazing about this rapid response is the fact that it could only have been the result of some sort of communication. This was not a case of some civilian report to the police, who then contacted the military. That would have taken hours, perhaps days. It had to be a direct message giving the geographic coordinates of the crash, since it occurred in a remote, mountainous area. It implies that the military had been in direct communication with the aliens. Since we already know that the Los Alamos scientists had a direct link to the alien planet, the sequence of events must have involved a report back to Serpo by the stranded crew, followed by a message to Los Alamos from Serpo, followed by an immediate message from Los Alamos to the response team.

According to the memo, it was later determined that the aliens in the monitoring craft had been very pleased with the humane treatment that we provided to the grounded disc crew. That means that obviously we had cordial relations with these ETs after the landing. That's the only way we could have received that feedback. The memo says that the aliens “had their own agenda. They were busy doing there [

sic

] own analysis of items provided in the quarantined area set up. This included: food, facilities, and us. It begin [

sic

] to appear that we were the captees [

sic

] and they were the captors.” The two uninjured aliens requested that they be allowed to reenter the craft. We agreed, but left the hatch open so that they could be observed. It was later realized that they were probably communicating with the monitoring craft. After they exited, all four aliens were taken away to a special habitat that we had already prepared for them in Los Alamos Laboratories, where they were given medical treatment and tests. The memo says that they “were secured in a medical facility that was manned by doctors, bioastronautic physicist[s] chemists, and linguist[s]. At this time communications was limited to basic sign language.” Again, that high degree of preparation clearly demonstrates that the entire operation was prearranged. That habitat at Los Alamos was evidently the same one created to house Ebe1 before his death one year earlier. The fact that the Kingman aliens were brought to the very same facility clearly implies that they were also Ebens.