Secret Journey to Planet Serpo (8 page)

A ROCKET SHIP TO HELL

In the memo, we learn of an interesting incident that occurred after the aliens had been taken away to Los Alamos. The military retrieval team decided to enter the craft. What followed was unexpected and bizarre. According to the memo, “a[n] entry crew was formed, they were dressed in clean room clothing with medical surgical masks. The size of the crew was not mentioned. Communications between the crew and the team out side [

sic

] was set up prior to entry. What happened with the entry crew while inside of the vessel was noted as follows: communications failed; the crew after one hour inside emerged from the craft confused, with up set [

sic

] stomachs, removed their masks and threw up. What was astonishing [was] they could not remember any of the inside details of the craft. When six months later, a member of that original entry crew, a fighter pilot, was asked if he would like to be part of a new entry crew, he replied, âI would rather take a rocket ship to hell than to go back into that craft.'” That experience clearly connects the Kingman craft with the alien ship that took the astronauts to Serpo. Several members of that team had the identical reaction when they first entered the Eben craft.

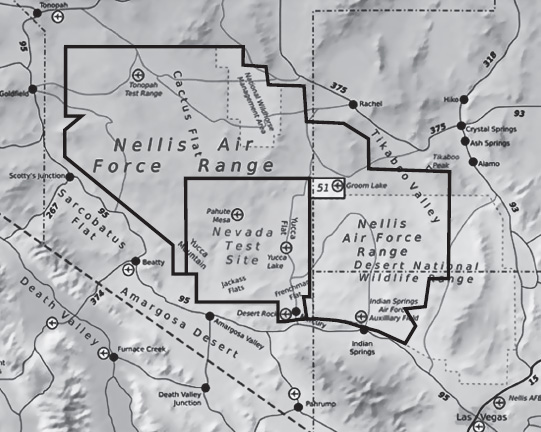

What is striking about this retrieval operation, according to the memo, is the fact that the military team came so completely equipped. They had with them a tank trailer used to transport Sherman tanks. That means that they had to know in advance the approximate size of the alien craft, which was exactly thirty feet in diameter. So obviously, the purpose of the entire incident was to give us the disc. Evidently, the aliens were on their way to the Nevada Test Site to land it there and then be taken to Los Alamos by bus. When they landed prematurely near Kingman, we sent the tank trailer. The crane on the tank retriever was able to lift the disc easily and load it onto the trailer. However, they were concerned about the overhang, which might have made the load too wide for city streets. But when they tried to tilt the craft, it proved impossible. So, according to the memo, “Finally it was decided to use the house method of movement utilizing roadblocks secured by military vehicles.” This was done, and the alien craft was taken to the Nevada Test Site.

Map showing the Nevada Test Site; note its proximity to Area 51

The scientists at the test site were frustrated by the reentry problem. Also, they found it difficult to concentrate because of a low humming sound that continued to emanate from inside the disc, and since they couldn't enter, they couldn't find the cause. Consequently, for six months they made no progress in analyzing the craft. So, since the four Ebens at Los Alamos wanted to return to the craft, it was decided to bring them to the Nevada Test Site. By this time, the tallest alien and the bioastronautic engineer had established a rudimentary form of communication. The four aliens entered the craft and after a few minutes the hum was silenced. Upon emerging, the tall alien asked the bioastronautic engineer to accompany him back inside. This was permitted. The memo says, “After sometime [

sic

] passed, both made their exit. The engineer looked well and smiling.” After that event, the Ebens' preferences were honored. They were allowed to be housed at the test site near their craft, and their requests for additional material, equipment, and literature were granted. Thus began a new phase of human-alien cooperation that allowed the reverse-engineering program to begin in earnest. That would have been sometime around November 1953.

In attempting to reconstruct the sequence of events that occurred after the alien craft landed near Kingman, it becomes clear by putting the two versions together that the scene that was staged for the benefit of the investigators must have taken place after the four live aliens had been packed off to Los Alamos. The dead Eben seen by Stancil could easily have been one of the ten that had been preserved cryogenically at Los Alamos, and was brought to the site on dry ice just to participate in the tableau to be observed by the fifteen investigatorsâa nifty piece of stagecraft presented by an ad hoc U.S. Air Force theater group!

See appendix 10 for a personal statement by Bill Uhouse, an American engineer who worked on duplicating the alien disc recovered at the Kingman site and building a disc simulator for training our pilots.

6

KENNEDY

Many years ago, the great British explorer George Mallory, who was to die on Mount Everest, was asked why did he want to climb it. He said, “Because it is there.” Well, space is there, and we're going to climb it, and the moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there. And, therefore, as we set sail we ask God's blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.

J

OHN

F. K

ENNEDY

, S

PEECH

AT

R

ICE

U

NIVERSITY

, S

EPTEMBER

12, 1962

President Kennedy was catapulted into the middle of world-shaking events in his very first year in office. Perhaps most important was Vostok 1, the successful orbital flight of Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin on April 12, 1961 (see

plate 7

). Even though Gagarin was in space for a short 108 minutes, and made only a single orbit, this was a shot across the bow for the United States because we weren't even close to matching that accomplishment, even though we had Wernher von Braun on our NASA team. Kennedy was galvanized by that event. Eight days later, he shot off a memo to Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, whom he had appointed as chairman of the Space Council, that asked the question, “Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to land on the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man? Is there any other space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win?” Kennedy was deeply committed to his New Frontier initiative, and space was the new frontier. Space travel was tops on his agenda, and he wasn't going to settle for second best to the Soviets. It clearly demonstrates the importance of this subject to Kennedy when it is realized that this memo to Johnson was sent only three days after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. One would think that explosive subject would have been uppermost in his mind. Just the previous day, several members of the invasion force had been executed by the Castro regime.

We now know from several sources, including Jacqueline Kennedy, how severely shaken Kennedy was over the Bay of Pigs debacle. And yet, only one month later, on May 25, 1961, he delivered his famous man-on-the-moon speech to a Joint Session of Congress, demonstrating, once more, his strong commitment to American triumphs in space. Kennedy's confidence that we could put a man on the moon by the end of the decade was based on von Braun's analysis, which had been solicited by Vice President Johnson. In von Braun's April 29 response to Vice President Johnson's inquiry he said, “We have an excellent chance of beating the Soviets to the first landing of a crew on the moon (including return capability, of course) . . . With an all-out crash program I think we could accomplish this objective in 1967/68.”

Metaphoric illustration of the Kennedy fallout over the Bay of Pigs debacle

President Kennedy and Wernher von Braun at the Marshall Space Fligh

t

Center at Redstone Arsenal, Huntsville, Alabama, 196

3

In his memo, von Braun also discussed funding the development of a nuclear rocket as a long-term goal for going beyond the moon to the exploration of space. In his speech to Congress, Kennedy asked for approval for development of the Rover nuclear rocket. He said, “This gives promise of some day providing a means for even more exciting and ambitious exploration of space, perhaps beyond the moon, perhaps to the very ends of the solar system itself.”

THE DIA INVOLVEMENT

The turf wars between intelligence agencies in the early 1960s was intense. Even before the Defense Intelligence Agency was created, the other agencies were highly protective of their sources and information, and reluctant to share power and influence with the other organizations. In 1947, Truman had created Majestic 12 (MJ-12), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the National Security Council (NSC). Then, in 1952 just before leaving office, Truman formed the National Security Agency (NSA) as a division of the Department of Defense. By the time President Kennedy took office in January 1961, the various agencies had staked out their own territories and resented intrusion into their affairs. In addition, each branch of the military had its own intelligence capability. The venerable Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), founded in 1882, was supremely influential and powerful, and probably trumped the youthful CIA in that decade, as did the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Further complicating this alphabet stew was the practice of compartmentalization. Secret information was kept contained at the various agencies as well as at different levels within each organization. Consequently, the likelihood that any single high-ranking individual knew what other high-ranking individuals knew was remote. All the intelligence paths met only at the level of MJ-12, and it was this above-top-secret and untouchable committee that pulled all the strings.

In mid-1961, the CIA blamed the failure of the Bay of Pigs operation on Kennedy because he refused to send in air support. U.S. Air Force General Charles Cabell, the deputy director of the CIA at the time, was the most outspoken in placing this blame, although the resentment was also shared by the CIA “foot soldier” participants in the raid. Kennedy, on the other hand, blamed the CIA for the botched operation, and then fired Allen Dulles, the longtime director of the CIA, as well as Cabell, and promised to break the CIA up into a thousand pieces. This resulted in unvarnished hatred of Kennedy by the CIA, and was most likely the principal motivating factor in prompting Kennedy to create the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) in October 1961. On one level, Kennedy hoped to eliminate military intelligence agency rivalries by combining them. However, in view of his feud with the CIA, it appears likely, in retrospect, that he hoped to have the DIA replace the CIA over time. Ironically, he achieved just the opposite result, as yet another intelligence agency rivalry was spawned. The CIA, it seems, was not so easily deposed. Just as with J. Edgar Hoover, they “knew where all the bodies were buried.”

DIA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

DIA emblem

In view of these rivalries, it is safe to conclude that whatever information the DIA obtained from the other intelligence agencies about events prior to its creation was probably given to them only reluctantly. Consequently, whatever intelligence it garnered about alien interactions in the period between 1947 and 1961 was almost certainly incomplete and unreliable, and possibly even included disinformation. DIA operatives had to depend mainly on MJ-12 for that information. So, if MJ-12 decided to withhold what they knew in the interests of compartmentalization, or if they shared any sort of anti-Kennedy bias, the DIA would be left completely uninformed and would be forced to start its operations in 1962 with a clean slate. And that seems to be what happened.

THE KENNEDY DIRECTIVE

Anonymous tells us that President Kennedy issued the directive for the Eben exchange program about six months into the planning for the return visit. That would have been around September 1962. That means that he was probably briefed on the EbenâLos Alamos communications history by MJ-12 around that time. As we noted earlier, the suggestion of an exchange program was first advanced in the fifth message to Serpo sent by Ebe1 in 1952, at the urging of the alien's military handlers, but presumably ultimately at the prompting of President Eisenhower. So this idea did not originate with Kennedy. In fact, he may have been persuaded to push this agenda by MJ-12. And that explains how the DIA came to be involved in the operation. Certainly, Kennedy would have wanted his new intelligence agency, firmly under the control of himself and Robert McNamara, to take over such a momentous and dangerous operation. It is perfectly understandable that he would have bypassed his old Bay of Pigs adversaries at the CIA to gain this control, even though he had already fired Director Allen Dulles and Deputy Director General Charles Cabell a year earlier. But there may have been a very important, but less obvious reason. There is evidence that Kennedy's distrust of the CIA had deeper rootsâthat he believed they did not necessarily serve the interests of any administration, but followed more of an independent agenda because they outlasted presidential terms. Although they did answer to congressional oversight, they had such a broad, international overview and so many deep secrets buried in their vaults that they were really powerful enough to do whatever they wanted. Because the DIA was new and was entirely Kennedy's creation, the president could be certain that this amazing story about space travel would not be used in the service of that independent agenda, but would eventually be given to the American people, who had the right to know about it.

But also, from what he knew, Kennedy may have considered the Ebens to be potential enemies at that point, so that makes DIA involvement very logical. After all, the DIA was charged with obtaining enemy intelligence, whether on or off this planet. And it may very well have been their recommendation that convinced Kennedy to agree to the exchange program in order to get as much information as possible about the Ebens' weaponry and motives. If Kennedy did harbor that mistrust, it is further evidence that he was not informed about the Kingman “crash” in 1953, and the subsequent interactions with the Ebens that took place under Eisenhower. That would also explain why none of that information was known by the DIA and released by Anonymous with the Serpo material in 2005. The DIA part of the narrative picks up with the training of the Serpo team in 1963. At that point, the agency was two years old, and had evidently just been brought into the operation by McNamara and Kennedy, so they would have had only those records in their archives.

If this assumption is correct, then Kennedy would have been led to believe that the return visit and the exchange program plan, now under the control of the DIA, constituted our entire agenda with the Ebens, while, in truth, we already had their representatives working with us on the reverse-engineering of their craft at Los Alamos, Area 51, and the Nevada Test Site, under the control of the CIA, the Air Force Office of Special Investigation, the Office of Naval Intelligence, and probably the National Security Agency (NSA). It seems likely that MJ-12 probably bowed to the wishes of the military and the CIA not to allow the DIA to get their hands on that program. They knew that if Kennedy had been given that information, he would almost certainly have complicated matters by trying to involve “his” intelligence organization, and to take over a mature operation, already well advanced over the last nine years. Thus began the era of limited presidential access to top secret affairs. From the point of that first precedent, MJ-12 controlled all interaction with the aliens, and gave the president only the information that, in their judgment, he had a need to know. President Eisenhower was the last president to be fully informed about our dealings with extraterrestrials, and there is reason to believe that even he was not told everything.

So, while the Kingman event was not included in the Serpo story released by Anonymous in 2005, it belongs in this narrative because it fully explains why the Air Force had no reticence about sending twelve Americans to a distant planet for a period of ten years. They were confident of the success of the mission because by the time President Kennedy had given the directive for the exchange program in 1962, the military had already been secretly dealing directly with the Ebens right here on Earth in a reverse-engineering program to duplicate their antigravity discs for nine years. By 1962, the CIA and the NSA had volumes of intelligence about the Ebens. We knew all about their history and their character, and had already established a working diplomatic relationship with their civilization. Furthermore, we were assured of their good intentions because they had given us, as a gift, an antigravity disc to use as a prototype, supported by Eben scientists to help implement our reverse-engineering program. In the absence of those nine years of direct interaction, sending those astronauts on an alien spaceship on a trip of thirty-eight light-years, based solely on some very questionable and shaky communications across the vastness of space, would have been a very risky, one might even say reckless, proposition indeed.

In view of this experience, the CIA and the NSA were perfectly willing to let Kennedy and the DIA take over the exchange program and to incur whatever risks existed. Physically going to their planet was the next logical step in developing a stable exopolitical relationship with the Ebens. They knew that Kennedy would never be able to take the credit for such a grand space triumph and to parade the success of the mission before the public because he would be out of office by the time the astronauts returned, which was expected to be 1975. This, in fact, may explain why the astronauts were sent to Serpo on such an extraordinarily long mission. It appears that this may have been planned so that Kennedy would have been retired from the presidency before they returned, even if he served two terms. They really had him in a straightjacket. Kennedy's silence about the Serpo adventure was critical. If it had been revealed to the public, it might have opened the entire Pandora's box containing all the secrets of our dealings with the Ebens in the reverse-engineering program. They knew how much he wanted a space-based accomplishment, so of course he would want the exchange program. But he had to keep quiet about it while it was in progress because it could have ended in disaster, and that disaster would, of course, have become his legacy as an ex-president if it had been known that it was he who had sent the astronauts to Serpo. It would be said that he had made a monumental error in judgment to have risked the lives of twelve Americans on such a fanciful and hazardous adventure, lacking the intelligence that such a journey required. He would not have had that intelligence because it wasn't shared by the CIA and the NSA. Kennedy knew nothing about what they had learned over the nine-year period since the Kingman event. Yet, because of his passion for his new frontier in space, he was willing to embark on what, to him, was a very high-risk adventure.

So MJ-12 got everything they wanted. They got the go-ahead for the exchange program from a new, inexperienced president who was committed to space travel. And because they did not share their comfort level with the Ebens with him, he believed that it was a very dangerous operation, and that he could not risk the catastrophic blow to his legacy as an ex-president if the twelve astronauts never returned to Earth. So they obtained his silence. They believed that they had manipulated President Kennedy perfectly. However, they left one factor out of the equation. By putting the operation in the hands of the DIA, Kennedy was ensuring that the entire story would eventually be revealed. He made certain that, at its basic level, this organization shared his dedication to government transparency. Kennedy had always been strongly opposed to secret societies and to government secrecy.

*16

He knew that, perhaps not in his lifetime, but in time, this incredible saga of the human journey to another star system would be revealed to the public so that we would begin to understand our place in galactic society. And so, forty-two years after his death, it was.

For more complete information about the DIA, see appendix 8.