Secrets at Sea (5 page)

Authors: Richard Peck

“You can say that again,” Aunt Fannie remarked, removing a single loose thread from her shawl.

Â

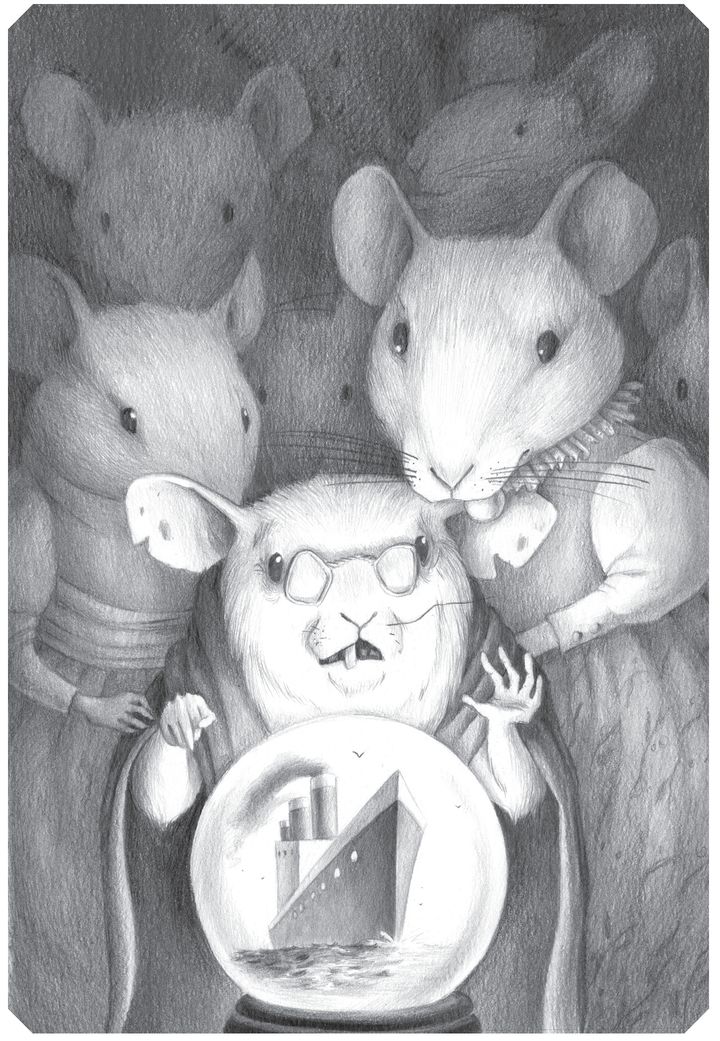

I TURNED TO go, my mind blank, my eyes blurry. But then behind me Aunt Fannie said,“Ah, that's better.” I looked back. Her nose grazed the crystal ball. Her specs gleamed. “Now we're getting somewhere. Here's your other future, Helena! Here's the one you can choose, if you dare.”

I stood there, between one future and another. The nieces edged up behind Aunt Fannie's throne to glimpse the future I might choose.

“Ohhhh,” they moaned.

Mona too. How provoking that Mona would gaze upon one of my futures before I myself. That moved me.

I elbowed her aside and peered down over Aunt Fannie's humped shoulder, into the depths of the marble.

No. Surely not. Anything butâ

“There it is.” Aunt Fannie tapped the crystal ball. “Plain as the nose on your face.”

“I couldn't,” I whispered. “We couldn't. How could we?”

Â

THE MARBLE WAS awash, and water is not a happy subject for us mice. Stormy gray seawater crashed in waves. The marble filled to overflowing. Great, surging mountains and valleys of wicked water. I felt wet through.

A ship too big for the marble to contain.

Cutting through the seething sea was the sharp prow of a ship. A great iron ship, trailing black smoke. A ship too big for the marble to contain, rising and falling in the restless water.

My stomach rose and fell.

“Well, there you have it.” Aunt Fannie thumped the dimming marble. Still, I caught sight of the light from row after row of portholes rippling yellow across black water before the marble went dark.

It was the great ocean liner carrying the Upstairs Cranstons to London, England.

“How wide is that . . . water?”

“It is called the Atlantic Ocean,” Aunt Fannie intoned, “and it is just at three thousand miles across.”

My sisters Vicky and Alice, and Mother too, had all been dragged to their dooms in a rain barrel not three

feet

across. Not

three feet.

feet

across. Not

three feet.

My throat was bone dry. “Mice don't crossâ”

“Mice better,” Aunt Fannie answered.

“But how in heaven's name?” I pled. “And how could I convince the others?”

Aunt Fannie adjusted her shawl. “That brainless brother of yours will welcome any reason to miss these last weeks of mouse school. He'd sooner drown than finish the semester.”

True.

“And Louise would risk her silly neck to be wherever Camilla Cranston goes.”

True, true. But Beatriceâ

“And that boy-crazy Beatrice has kept Gideon McSorley a secret. She dare not refuse to leave him, or she will be found out!”

Aunt Fannie looked particularly proud of her reasoning.

Oh, I thought.

“There is nothing I wouldn't do to keep the family together,” I said in a voice gone weak as ... water. “Nothing. After all, I am Helena, theâ”

“Then you will have to go to great lengths.” Aunt Fannie fingered a final whisker. “Great lengths indeed. Across land and sea, water and the world!” She shook a fist at the heavens. “A world of steam and humans and long, long distance!”

The nieces quaked and clung to one another. She waved the crystal ball away. “Sit down, Helena, to learn what you will need to know.”

All the nieces flopped right down and arranged their tails. They were agog and waited wide-eared to hear. So did I, of course.

But Aunt Fannie did a strange thing then. Mysterious. “Here is how you hold your family together,” she said. Then she put out both her old hands, stretched wide open.

“That's how you hold on to family.” She thrust her wide-open hands right at me. Right in my face.

But what could that mean? What in the world?

CHAPTER SIX

A World of Steam and Humans

W

E SAILED AWAY to London, England, Louise and Beatrice, Lamont and I. We began our journey by steamer trunkâthat biggest trunk that had stood open for days in Camilla's bedroom, filling up with her new finery. It had drawers inside.

E SAILED AWAY to London, England, Louise and Beatrice, Lamont and I. We began our journey by steamer trunkâthat biggest trunk that had stood open for days in Camilla's bedroom, filling up with her new finery. It had drawers inside.

We packed a morsel of food, for we little knew where our next meal was coming from. But we took not a stitch of clothes, as we had no luggage. Mice don't. Still, fur is perfectly suitable for traveling. Lamont naturally wanted to take everything he had. Boys collect thingsâanything useless. Lamont wanted to take all his collections: the birds' bones and the collar buttons and that ball of twine that kept getting bigger and bigger in his room. He was a regular pack rat, though smaller. “No, Lamont,” I told him.

We sisters were to travel in the handkerchief drawer of Camilla's trunk, in among her sachets. Lamont went in the top drawer above us, in with Camilla's gloves and garters. It was the best we could do.

Before dawn, we swarmed up through the house, never daring a backward look. By the time the sun of that last morning crept across Camilla's sleeping form, we were hunkered, lurking within the drawers. Beatrice and Louise and I were nose to nose to nose, under the lacy edges of Camilla's handkerchiefs. It was a small drawer. There wasn't room to swing a . . . cat.

A scent of Mrs. Flint's coffee wafted up from the kitchen, and the house woke around us. Mrs. Cranston dithered up and down the hall. Mr. Cranston barked commands nobody obeyed. Olive and Camilla chattered from room to room as they seemed to be tying on their traveling veils and fur tippets. We lurked in our drawer, all ears.

What if Camilla reached in for a handkerchief at the last moment? We hardly breathed.

Then the men were there for the trunks. Rough hands slammed our trunk shut. We were all three dashed against the far wall of the drawer in a tangle of Camilla's handkerchiefs and the leftover apple fritter.

Above us, we heard Lamont bounce off every side of the glove and garter drawer. Beatrice clung to me. Louise braced both feet as we slanted down the stairs on some big bruiser's back. Then off the front porch and into the wagon bed. The Cranstons were traveling with a wagonload of steamer trunks. We sensed them piled around us, like coffins.

“Are we over water yet?” frantic Beatrice whispered before they'd had time to turn the horses.

Â

A TERRIBLE DAY followed. We traveled at great speed and blind as bats. On and off express wagons. On and off the clanking train. Before we reached the gangplank at New York City, they dropped us once on cobblestones. We were knocked half senseless. One of my ears got bent and took forever to straighten out again.

Now we sensed water below. The damp crept in. Waves lapped the pilings. The blast of the ship's horn shook the world. We couldn't see a moment ahead. We couldn't see anything. Louise whimpered. Beatrice clung. I'd have taken my chances back home. Gladly. But you can't go back, not in this life. You have to go forward.

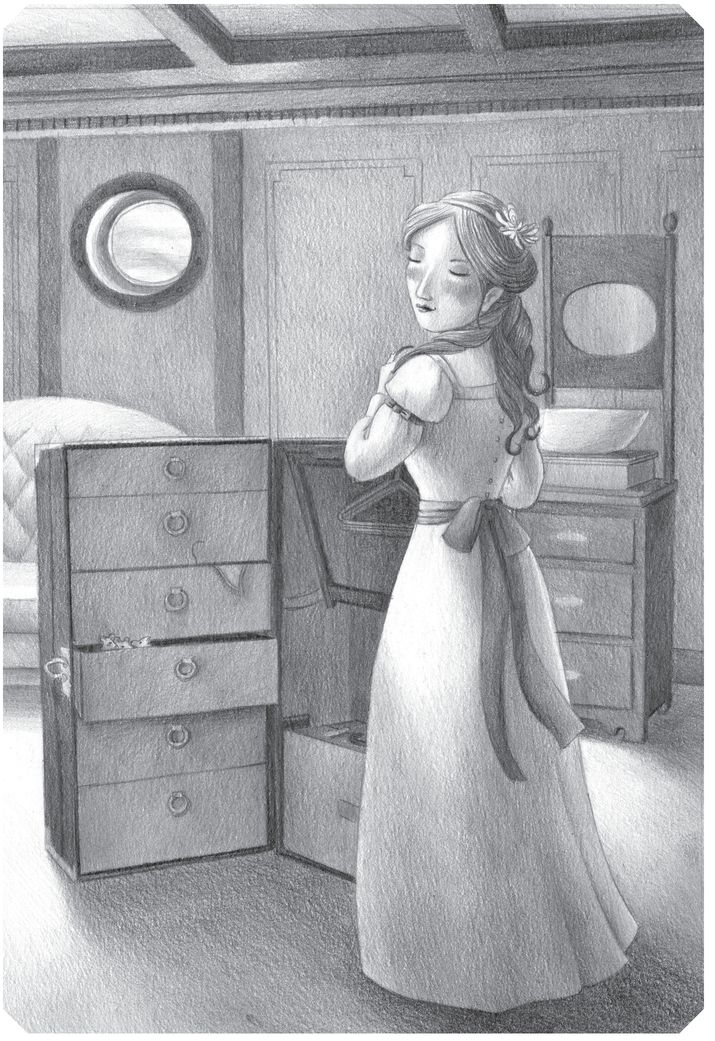

AS NIGHT FINALLY fell, our trunk stood yawning open in Camilla's shadowy, swaying cabin. A band played in the distance. Bells rang. Whistles shrilled. All the humans seemed to be up on deck, watching us sail. But Camilla would be back soon, to unpack. Then what?

Then she was there, all over the cabin. She unwound her traveling veils and threw off her fur tippet. She unpinned her hat and rummaged in her jewelry case. We watched her through the crack in the drawer.

She was shortly down to her petticoats and pearls, and heading our way. We cowered as she searched through the hangers for her dinner dress. She pulled out the lavender one.

Beside me, Louise went to work, sorting through the handkerchiefs for the one embroidered with violets. She nosed it to the crack in the drawer. It would be the first one Camilla's fingers would find, and it went with her dress. She only had to open the drawer an inch, and the handkerchief practically popped out at her.

We watched her through the crack in the drawer.

Camilla thrust it into the sash at her waist.

Now she was remembering she'd need her long white gloves. Gloves! She reached for the drawer above us. Imagine reaching for your gloves and getting a handful of Lamont.

The glove and garter drawer slid open. We braced for Camilla's screams.

But no sound came. Now she was at the mirror, pinching her cheeks for extra color. The pair of long white gloves lay draped with the fur tippet over a chair arm. One glove twitched. A furry ball, tightly furled, fell out of it. Lamont.

From somewhere a dinner gong sounded. Camilla was out of the door, pulling on her gloves. Camilla always had a pleasant, girlish way of darting about that Louise tried to copy.

We waited, all ears, as the Upstairs Cranstons gathered in the corridor outside. Skirts sighed. Mr. Cranston grumbled. Mrs. Cranston dithered, and her corsets creaked. And Olive no doubt caught her toe in the carpet as they set off for the first-class dining saloon. Olive was never at her best around her mother.

Our drawer was still a little ajar. We peered out. The electrified lamp above the dressing table still glowed. There was nothing to dropping down, though there'd be no going back. Somebody would be clearing out the drawers and storing things in cupboards. They'd find crumbs of apple fritter in our drawer. Heaven knows what they'd find in Lamont's.

We dropped, and landed on our feet. We always do. There on the carpet was Lamont, cool as a cucumber, as if we'd taken ages. We huddled, and I tried to keep us together, but it was like herding . . . cats.

We glanced past the trunk, around the flowered chamber pot beneath the bed. The cabin was small, nowhere near the size of Camilla's bedroom back home.

“At least she doesn't have to share with Olive,” Louise remarked. “That would have made the trip endless for her. They'd be running into each other all the way across the you-know-what.”

It was an elegant cabin with two portholes. The walls were paneled in satiny wood.

“At home we lived inside the walls,” piped Lamont, stroking his chin, though he doesn't really have a chin. “Maybe we couldâ”

“Don't even think about it.”

The voice came from above us. We jumped and reached for each other. It wasn't a human voice. It didn't blare or echo. It was more like one of us, but different.

“That's solid sheet metal you 'ave there behind the wood on them bulkheads,” came the voice in rather an odd accent. “Good British sheet metal.”

We looked up. Camilla's fur tippet stirred on the chair. We were riveted. Two eyes, redder than rubies, looked down at us. Camilla's furs parted, and a head appeared, then an entire mouse, snow-white. A big mouse. Full-grown and then some, in the prime of life. Gorgeous whiskers.

Drawing up, he planted a hand on his big haunch and gave us the once-over. We must have thought we were the only mice on the Atlantic Ocean. But no.

Other books

I Should Be So Lucky by Judy Astley

The Sheikh's Destiny by Olivia Gates

Highland Hawk: Highland Brides #7 by Greiman, Lois

The Infinity Brigade #1 Stone Cold by Andrew Beery

The Forgotten Army by Doctor Who

Return to Eden by Ching, G.P.

Wellesley Wives (New England Trilogy) by Duffy, Suzy

The Beach Wedding (Married in Malibu Book 1) by Lucy Kevin, Bella Andre

Letting Ana Go by Anonymous

Electrify Me (The Fireworks Series Book 1) by Rizer, Bibi