Serpents in the Cold (32 page)

Read Serpents in the Cold Online

Authors: Thomas O'Malley

Foley's jaws clenched. He closed his eyes for a moment, and his Adam's apple bobbed up and down. “Cal,” he said, “you know I would never do what you're saying, that I never meant to hurt Sheila. It was an accident, you have to believe thatâyou don't understand how I loved her. If it wasn't for her and Rizzoâ”

“Cal,” Dante said. “Cal.”

Cal looked at him.

“Bundle up the baby and take her out to the car.”

Cal stared at Dante for a moment, questioning, then nodded and stood. His eyes flickered momentarily over the congressman's face and then back to the baby.

“You can't take my child,” the congressman said.

Dante spoke again to Cal. “Wrap her up good in blankets. Turn the car on so it's warm.”

Cal took a large blanket from the couch and stood before the congressman.

“Move your arm,” he said.

“You can't do this.”

“Move your arm now.”

Dante took the .38 revolver from his pocket, aimed it at Foley. “Do as he says.”

The congressman pulled his arm back from the infant, and Cal gently lifted the baby from his chest, bundled her into the blankets in one swift movement, and lay her snoring against his shoulder.

“Cal, you know this isn't right,” the congressman called as Cal left the room. “Cal!”

The congressman gripped the arms of the chair. “Dante, you don't need to do this. Think of what this means for the child. Look at what I have to offer herâa good home, a good school. She'll never want for anything. What can you give her? She'll be living on the streets, no better than Sheila was when I first met her.”

“You're right. I should let the man that killed her mother watch over her.”

“I won't let you get away with this.”

Dante cocked his head toward the hallway, waited several minutes until he heard the front door open and then close, imagined Cal's careful footsteps above the snow-flecked gravel, bending his body to protect the child from the wind and the snow. The last few remaining embers crackled in the hearth.

“Dante,” the congressman began, “I was wrong, there doesn't need to be trouble between us. I only want what's best for Sheila's daughter, for

my

daughterâ”

The stylus lifted off the record, and Dante waited for the needle to settle into the groove again. A long

hissssss

preceded the soprano's voice. He stared at the congressman as the soprano's voice rose up the scales. It resounded in the quiet of the room, pressed loudly in Dante's skull till he could hear nothing else, so that when he spoke, his voice seemed strange and faraway, as if coming from across some great distance.

“Who ever said she was your daughter?” he said and his gun boomed in the small blue room, obliterating everything else.

_________________________

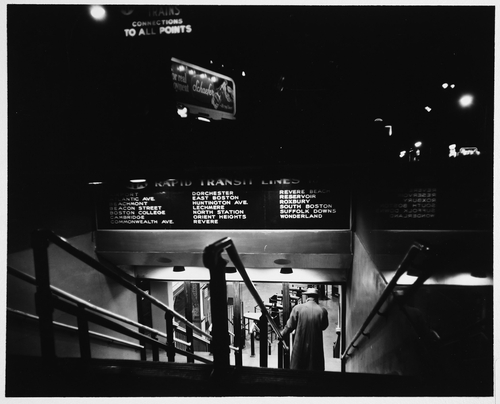

Scollay Square, Downtown

IT TOOK A

long time to drive back to Boston. There were more snow flurries, and Cal kept up a low moaning as he negotiated the winding roads out of Gloucester and along the coast. To Dante it sounded as if he were at prayer, chanting to the saints, his head lowered and squinting against the snow and the ever-disappearing boundaries of the road before them. Dante held the baby against him, using his heavily bandaged shoulder as a cushion for her head, and leaned back in the seat. So far she'd slept the entire way. His anxiety about holding her had gradually lessened as he watched and listened to her in sleep, and he studied the small moon of a face.

Cal glanced in the rearview at the two of them in the backseat. “What do you think Claudia will make of it?”

“I think,” Dante began, and then paused. “I think it will make her happy.”

“You think we were right to do what we did?”

Dante remained silent. He stared at the baby asleep in his arms. The wind rocked the car lightly.

“I'm not sure about what's right.”

“The law wouldn't see it that way.”

“The law didn't do much for Sheila, did it?”

“Are you going to lose sleep about it?”

“No.”

“Well, good, then.”

Â

BOSTON WAS DESERTED.

Swirls of snow swept over the sidewalks, and in the roadway the tracks of cars were lined with brownish slush. The car's chains tapped and clanked in the places where the roads had been cleared, sparking briefly on the desolate streets. The frame houses and triple-deckers crouched against the cold and the snow, and they seemed to shudder with each gale. A trolley car trundled up the avenue, showering blue sparks as it dragged the power lines. The streets seemed empty and dark; Cal peered at the houses as they passed.

“All the lines are down. The electricity's out.”

“We'll be fine,” Dante said.

“I'm just thinking of the baby.”

They drove through Scollay Square and pulled up before the building with its crenulated black fire escape dripping with dark icicles before each shuttered window. A halite sheen on the recently shoveled steps glowed like silver. For a moment they sat in the warmth of the car, waiting, and watching the streets. A few bums sheltered in the alleyway before Moran's. A couple exited the butcher shop and quickly crossed the street to Kendall's pharmacy. Other than that, the street was deserted.

A deep bone-tired weariness came upon the both of them as they sat in the last of the heat escaping quickly from the car. In the silence the baby's soft, insistent, yet fragile breathing filled the interior of the car. Cal glanced at Dante in the rearview, and Dante nodded, climbed out of the car with the baby bundled against his tattered coat. Cal watched as Dante took the steps slowly, the baby held tight against his bowed chest, the wind whipping the coat about him, and then he opened the front doors to the building and stepped inside.

_________________________

Kelly's Rose, Scollay Square

DANTE STARED INTO

the mirror above the sink, the mercury plating showing through the cracked surface corroded by mildew and age, and saw only himself transfixed in the stark light cast by the bare lightbulb dangling from the ceiling. He left the toilets and walked down the hallway, stepped to the door of the bar, and opened it. For a moment everything seemed to slow: Cal at the bar, sunlight slanting down the scarred mahogany glinting off glass so that at first he was merely a black silhouette, and then from the brightness emerged his face, and Dante stepped forward, into the light, and the door to the hallway banged shut behind him.

“You all right?” Cal asked, hand momentarily paused around his glass, brow pinched in concern.

“Yeah.” Dante nodded, sipped from his drink, and then smiled. “I'm good.”

Cal looked at him for a moment longer. Dante fumbled with his pack of cigarettes, put one between his lips but didn't light it.

“There'll be a lot waiting for us when this storm ends.”

Cal swallowed his whiskey, grimaced. “Don't worry about it.”

“Don't you think they'll link it back to us?”

Cal squinted at the window rattling as the wind moved the snow sideways, swirling before the glass. “They won't find him for days, and with all this snow, they'll have to dig him out. Everybody knows Blackie was searching for the Brink's money. Maybe they'll figure that's the connection.”

“What do you think became of the money?”

Cal shrugged. “I don't think we'll ever know. Whoever got the money is probably sunning it up poolside in Acapulco, a cocktail to his lips and a couple of girls on either side of him.”

A man entered the bar, his mouth covered by a thick scarf. Eyes squinted in a face made ruddy by the cold and swollen by booze. He shuffled to one corner of the bar and sat down heavily. Outside the sun had disappeared again behind low, thick snow clouds, and the street was still. The bartender placed a glass before the man and then turned on the radio at the back of the bar. It took a moment for the radio to warm up, its transistors humming loudly, and then through the crackling speakers came the Rosenberg trial and the bartender fiddled with the knob until he found the hockey game. The Bruins were beating the Canadiens, 3â1, but had already been eliminated from the playoffs.

Wind pressed against the bar's window so that the glass seemed to bend. When it eased, a strange silence followed. Cal sipped from his drink, pursed his lips. The bartender glanced at them while he worked the dial on the radio above the bar as the signal faded and they lost the game. “Worst storm in history, the papers say,” he said.

Cal nodded, and Dante stared toward the snow-streaked windows. Outside, jagged-looking icicles quivered and the flattened shapes of passersby marked the slow decline toward a dusk indeterminate and indistinguishable from day. The radio whistled, high and piercing.

“We'll have another round over here,” Cal called, but the bartender could no longer hear him over the squeal of the radio and the wind against the transom and Cal and Dante emptied their glasses and waited.

|

|

ï

Scollay Square

ON THE TOP

floor of the derelict Anvil Building, whose gilded molding and frescoed façade had once so elegantly greeted tourists and sailors and out-of-towners to the Square, a handful of homeless men pressed around a large rusted barrel in which a fire blazed. Through holes punched in the metal sides, orange flames pushed back the darkness and the cold.

The vagrants stood around the blazing barrel and fed it with paper, wood, and the cheap ashy coal that one of them had stolen from the coal tipple at the rail yard. The flickering orange flames cast shadows writhing across the floor and walls, where here and there the plaster was torn away exposing the horsehair and lath beneath. Through the splintered lath the exposed copper wiring hung from the walls like the guts of some eviscerated animal. The wind howled in the corners, hammering against the bare clapboard and through the frame, and they squeezed together for warmth, pressed up to the barrel against the holes they'd punctured in its side and from which the orange glow leaped. One of the men placed a thin, flat iron grate across the top of the barrel, and someone laid four potatoes on it.

The biggest man stood by the barrel idly whistling “The Wild Colonial Boy.” Another took a swig from the bottle they were passing around, and handed it to the blind man. He looked up with pale, whitewashed eyes, but his hand, swift and assured, closed around the bottle and brought it to his mouth.

Searching for more wood to burn, one of the men shuffled to the corner of the room where odd remnants of furniture had been left behind, two-by-fours that they'd pried from the floor joists and sections of paneling they'd torn from the walls. From the floor-to-ceiling windows, one of the men looked out upon the Square, at the Old Vic, the Howard Athenaeum, the Scollay Theatre, at its smoke shops, taprooms, hash houses, and liquor stores, the marquee billboards filled with faded pictures of the women who had once performed there: nude legs parted and scissored in the air, large bared and glistening breasts with tasseled nipples, a row of plump, oiled bottoms raised toward some unseen audience of men, and the performers looking back over their shoulders at the ghosts of another time.

The man looked toward the Old Vic with its awning bowed and warped by the weight of snow and ice. Its marquee bulbs continued to blaze even though it was shut down for the night. Its upper windows were mostly dark. Here and there a shadow moved behind an amber-hued shade, stood in that warm rectangle of golden light, something so small and brief and insignificant in all that darkness that it seemed to intensify the sense of isolation and emptiness so that the feeling of desolation grew larger still. From so high up, the whole street seemed like some vast ocean liner abandoned at sea, its once elegant salons and stairwells and ballrooms dark and empty now, absent of laughter or joy or life, as if everyone had left her to the terrible sea and she merely awaited her end.

The flames cast their orange light amid the debris, the soiled mattresses and threadbare, hollowed-out chairs and sofas, the piles of horsehair blankets, and the cardboard and timber lean-to at the far end of the room where they squatted to relieve themselves. Even with the cold, the room smelled of human waste. In the coming months the wrecking ball and the bulldozers will reduce the building to rubble, but the man and the others will already have moved on to another section of the Square, seeking shelter in one abandoned building after another until there are no more left, and the Square and its illustrious and shadowed past is gone.

The skin of the potatoes began to brown, and the smell of it made their bellies roil with hunger. The men crowded for space around the barrel. Their bottle was empty, but tonight they felt lucky, for someone appeared with another. At times the men looked upward through the latticework of joists and roof beams to the stars, and as they became inebriated, that view held their gaze, the momentary flicker of another lifetime pulled achingly at their thoughts. Their shadows lengthened, stretched sinuously across the wide-planked floor of the loft and into the dark corners where the rats scuttled, and the moaning of the wind echoed through the old building.

In the crawl space between the plaster lath and the exterior wall, tightly pressed together, lay half a dozen large square packages wrapped in black plastic bags. Orange flame light and black shadow spilled between the cracks and gaps and coalesced like oil upon their surfaces. Over the last couple of weeks, the rats had been at the bags, shredding the paper they held, using it for bedding. When the wind sheared down through the torn flashing at the edges of the roof and inside the clapboard walls of the Anvil, it sent the wrapping of the parcels shuddering, their loose corners flapping. Two rats scurried across one of them, nibbled absently at its corner, and then, pausing to listen to the muted sound of men from the other room, moved on, pale tails flashing in the orange light. From the torn hole gaped the shredded edge of a stack of thousand-dollar bills. A banknote fluttered in the wind, and then the wind took it and then another and, slowly, one by one, ripped the contents of the bag clean away.