Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire (28 page)

Read Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire Online

Authors: Eric Berkowitz

Speak plainly and say “fuck,” “prick,” “cunt,” and “ass” if you want anyone except the scholars at the University of Rome to understand you. You with your “rope in the ring,” your “obelisk in the Coliseum,” your “leek in the garden,” your “key in the lock,” your “bolt in the door,” your “pestle in the mortar,” your “nightingale in the nest,” your “tree in the ditch,” your “syringe in the valve,” your “sword in the scabbard,” not to mention your “stake,” your “crozier,” your “parsnip,” your “little monkey,” your “this,” your “that,” your “him,” your “her,” your “apples” . . . “carrot,” “root,” and all the shit there is—why don’t you say yes when you mean yes and no when you mean no, or else keep it to yourself.

The new crop of budding pornographers took this as sound marketing advice, and set about supplying Europe with cheap, explicit works.

When dirty books left the academy and spread to a broad base of readers, authorities decided something had to be done. At first, the menace of the printing press was more about religion and power than sex. By the mid-sixteenth century, when sexual censorship began in earnest, the Catholic Church was already in a very touchy mood. It had been bad enough when that malcontent Luther hammered his Ninety-five Theses to a church door; much worse was the spread of the theses, in print, throughout Christendom. Luther was the world’s first best-selling author. By 1520, his assault on the church had sold more than three hundred thousand printed copies virtually everywhere in Europe—and this was

before

he published his German translation of the Bible, which allowed millions of people to bypass the Catholic Church altogether when they prayed. (Luther was excommunicated in 1521, but the sales of his books continued to rise.) The Protestant Reformation could never have been as effective without the printing press to disseminate its key texts.

Meanwhile, the Vatican’s sex secrets were seeping out. The painter Giulio Romano had drawn sixteen hard-core pictures, each depicting various forms of copulation, which found their way to the walls of the Sala di Constantino in the Vatican. Given that the audience was limited to churchmen and their invitees, the pictures caused no controversy and were, no doubt, well appreciated. But when the prominent engraver Marcantonio Raimondi reproduced them for mass circulation in 1524, he was thrown into a Vatican jail cell. Raimondi languished there for more than a year, freed only after the irrepressible writer and satirist Pietro Aretino interceded on his behalf with Pope Clement VII. Had all of Raimondi’s prints and plates been destroyed as the Vatican insisted, the matter might have ended there—but Aretino’s interest had been piqued. Curious to see what all the fuss was about, he had a look, and then set about writing scandalous verses for each one, declaring:

I desired to see those pictures which had caused the [Vatican] to cry out that the worthy artist ought to be crucified. As soon as I gazed at them, I was touched by the spirit that had moved Giulio Romano to draw them. And since poets and sculptors, in order to amuse themselves, have often written or carved lascivious objects such as the marble satyr in Chigi Palace attempting to rape a boy, I tossed out the sonnets at the foot [of each of the drawings]. With all due respect to hypocrites, I dedicate these lustful pieces to you, heedless of the scurvy strictures and asinine laws which forbid the eyes to see the very things that delight them most . . . What wrong is there in seeing a man mount a woman?

Aretino published his sixteen lusty sonnets in 1537, along with the Romano/Raimondi engravings, in a volume called

Sonetti lussuriosi

(though the work soon came to be known as

Aretino’s Postures

). As soon as they were released, the pope himself ordered all copies of the work destroyed, but some survived. Aretino still managed to put out another edition, which was also suppressed. By that time, however, the work was being reprinted all over Europe in multiple pirated editions.

Ever the self-promoter, Aretino touted his sonnets as a groundbreaking effort to portray sex not as high art, but as body parts doing what they do best. His opening lines declare his intentions:

This is not a book of sonnets . . .

But here there are indescribable pricks

And the cunt and the ass that place them

Just like a candy in a box.

Here there are people who fuck and are fucked.

And anatomies of cunts and pricks

And asses filled with many lost souls.

Here one fucks in more lovely ways,

Than were ever seen

Within any whorish hierarchies.

In the end only fools

Are disgusted at such tasty morsels

And God forgive anyone who does not fuck in the ass.

In the same way the breakout success of

Deep Throat

defined the pornographic film explosion of the 1970s,

Aretino’s Postures

represented the apogee of sixteenth-century mass-produced obscenity. To be sure, there were other successful works in circulation that were no less vulgar, but none had Aretino’s reach or influence. The Sienese aristocrat Antonio Vignali, for example, produced

La Cazzaria

(

The Book of the Prick

), in which he depicted Siena’s political scene as a struggle between patrician Pricks (Big and Little) and Cunts (Ugly and Pretty), aristocratic Balls, and plebeian Assholes. But for all Vignali’s charming profanity,

La Cazzaria

was intended primarily as a political read, not a sexually stimulating one. Only a tiny group of cognoscenti could understand the jokes. Aretino’s readers, by contrast, needed no prep course to get it. His sonnets were satiric, but also stood on their own as purely titillating works. One sonnet, accompanying an image of an aroused man standing over a woman while holding her legs, made its point clearly:

Open your thighs so I can look straight

At your beautiful ass and cunt in my face,

An ass equal to paradise in its enjoyment,

A cunt that melts hearts through the kidneys.

Aretino’s works spawned legions of imitators, some of whom published under his name, but none of them reached the Italian’s iconic status. By the end of the century, an Italian phrasebook for English tourists included a dialogue in which an Englishman asks a Roman book dealer for “the works of A[retino],” only to be told: “You may seek them from one end of the row to the other, and not find them . . . [b]ecause they are forbidden.” Other booksellers were not so discreet. A Venetian in Paris claimed to have sold more than fifty copies of Aretino’s works in less than a year. In England, two professors at Oxford’s All Souls College were caught in 1675 using the school’s press to print off copies of

Aretino’s Postures

, presumably to profit from strong local demand. Sex always sells, but forbidden sex sells better: The banning of Aretino’s works increased their allure. The more the authorities tried to suppress them, the more sought after they became.

Aretino’s Postures

joined the select company of the works of Martin Luther, Giovanni Boccaccio, Johannes Kepler, and Niccolò Machiavelli, among others, in the Vatican’s first

Index librorum prohibitorum

(“List of Forbidden Books”) in 1559. The

Index

emerged from the Council of Trent, a landmark Catholic council held over twenty-five sessions from 1545 to 1563. It was primarily intended to suppress heretical works and the writings of Protestants, but also banned books concerning “things lascivious or obscene.” As stated in the council’s canons and decrees:

[N]ot only the matter of faith but also that of morals, which are usually corrupted through the reading of such books, must be taken into consideration, and those who possess them are to be severely punished by the bishops. Ancient books written by heathensmay by reason of their elegance and quality of style be permitted,but by no means read to children.

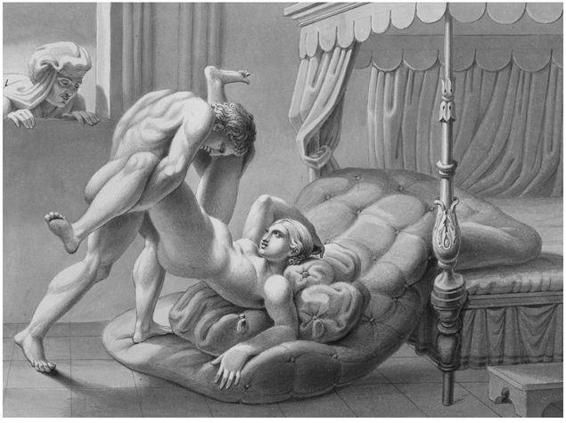

FOUR POSTER BED

One of Europe’s most enduring works of popular pornography, which was immortalized when it was placed on the Vatican’s first “List of Forbidden Books,” was a collection of smutty sonnets written by Pietro Aretino accompanied by a series of explicit engravings. The book, commonly known as

Aretino’s Postures

, was widely copied, reprinted, and censored. This image corresponds to Aretino’s Sonnet No. 11. “Open your thighs,” commands the man to his recumbent prey, “so I can look straight at your beautiful ass and cunt in my face.”

©THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

The church had gone prudish, right down to covering up the exposed genitals of the figures in Michelangelo’s famous Sistine Chapel fresco,

The Last Judgment

, with painted wisps of fabric and fig leaves. However, a maturing pornographic consumer culture was already in place, and nothing could eliminate it. If printing Aretino’s works in Italy was dicey, less regulated English and Dutch printers were only too happy to do the job. Getting hold of pornography was as easy as buying liquor in the United States during Prohibition. By the end of the sixteenth century, erotic images were sold openly in Venice’s Piazza San Marco along with sexy depictions of famous courtesans.

7

With its

Index

and attacks on

Aretino’s Postures

, the church was first out of the gate in the race to halt the spread of pornography, but its influence would not last. In France, Sorbonne University theologians ran the censorship business until 1618, when civil authorities began to take control of sex on the printed page. The disappointed professors were left only with the right to condemn unsanctioned religious books. A key stage in this power struggle was the state prosecution of a trashy little collection of verse put out by a Paris printer in 1622. The book,

Le Parnasse des poètes satyriques

, featured a sonnet by Théophile de Viau:

Phyllis, tout est f . . . , je meurs de la vérole,

Elle exerce sur moi sa dernière rigueur:

Mon v . . . baisse la tête et n’a point de vigueur,

Un ulcère puant a gâté ma parole.

J’ai sué trente jours, j’ai vomi de la colle;

Jamais de si grands maux n’eurent tant de longueur:

L’esprit le plus constant fût mort à ma langueur,

Et mon affliction n’a rien qui la console.

Mes amis plus secrets ne m’osent approcher;

Moi-même, en cet état, je ne m’ose toucher.

Phyllis, le mal me vient de vous avoir f . . . !

Mon Dieu! je me repens d’avoir si mal vécu,

Et si votre courroux à ce coup ne me tue,

Je fais vœu désormais de ne f . . . qu’en cul!

(Phyllis, everything is all f . . . up; I’m dying of syphilis,

It’s attacking me with all its might;

My c . . . lowers its head and has no strength

A stinking ulcer has spoiled my speech.

I sweated for thirty days, I vomited paste;

Never did such great pains last for so long;

The most steadfast spirit would have died from such languor,

And my affliction has nothing to console it.

My most intimate friends do not care to come near me;

Even I dare not touch myself in this state.

Phyllis, I caught the disease from f . . . you!

My God, I repent of having so badly lived,

And if your anger does not kill me this time,

I swear from now on to f . . . only in the ass!)

At the time, replacing words with ellipses or single letters was usually sufficient to avoid trouble with the law. The one body part spelled out in the poem—

cul

(“ass”)—sparked legal proceedings that eventually brought de Viau down. Not long after the book’s publication, the Parlement de Paris issued an order for his arrest, which he avoided by leaving town. He was then burned in effigy.

It would have likely ended there, the matter forgotten, had not a Jesuit fanatic called Father François Garasse become fixated on de Viau and

Le Parnasse

—especially the passage about “f . . . [ing] only in the ass.” Garasse published a lengthy book soon after the trial in which he attacked de Viau as a drunkard and sexual degenerate. The “ass f . . . er” in the poem was de Viau himself, Garasse argued, a lowlife “freethinker” who “has contracted an infamous disease from a prostitute, and swears to God to remain a SODOMITE all the rest of his days” (capital letters original). Sodomy carried a death penalty, which is exactly what Garasse sought. A month after de Viau’s effigy was set aflame, police arrested the poet himself and put him in a miserable Paris dungeon. He remained there for two years while defending himself.