Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire (25 page)

Read Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire Online

Authors: Eric Berkowitz

From that point forward, Pierre and Jean were tied to each other by much more than the same parents. They and their families were bound to a common future. Typically, the brothers’ agreement also specified that they would both contribute the dowry of their daughters. Pierre was already married, but the contract added that if Jean married, his wife’s dowry would become part of their common fund.

Not all parties to

affrèrement

contracts were related. Many people from different families formed

affrèrements

, especially after the plague had depopulated the land and made an abundance of cheap land available. As the survivors plucked up abandoned property and formed large personal holdings,

affrèrements

were the most convenient legal instruments for them to work collectively. In Provence, the Black Death left vast stretches of land ready for the taking. The foreigners who came in to settle the terrain frequently formed

affrèrements.

However, no one entered into these contracts purely for business reasons; they were deeply personal commitments.

Affrèrements

were opportunities for people, in effect, to create families on the basis of love and mutual interest rather than reproductive chance.

Loving male couples were in the minority of

affrères

, but they were there. When, for example, Jean Rey’s wife (“a bad woman”) left him around 1446, Rey turned to his friend Colrat with whom he shared an intense “affection, affinity, and love . . . from the heart.” Rey and Colrat contracted an

affrèrement

under which they agreed to live and work together for life. Their relationship was probably sexual at least some of the time, but that is not entirely the point. The fact is that the two men were able to fashion a life in which they were joined emotionally and economically under one roof. Contracts similar to

affrèrements

had been around for centuries in one form or another, but surged during the period roughly corresponding to the repression of same-sex marriage unions.

Affrèrements

had just the right amount of ambiguity within which homosexual behavior could be overlooked. The community accepted that two men who loved each other could live together. More than that, no one wanted to know.

In a sense,

affrèrements

were an early application of a “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy for homosexual relationships. At least until the sixteenth century, when the custom finally died out, same-sex couples were often permitted to join society as full participants so long as they did not mimic religious heterosexual marriage institutions too closely. The resemblance to present-day controversies over gay marriage is unmistakable. The most vocal opponents of marriage among homosexuals routinely cite the imaginary “history” of marriage as a sacrament only between a man and a woman, with its prime purpose being the production of children. This argument won a key victory in the United States in 1996, when President Bill Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act, which states that “the word ‘marriage’ means only a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife.” But church-sponsored same-sex unions and

affrèrements

reveal a much more textured historical picture. Just as the law of the Middle Ages forbade “unnatural” sexual acts, so did it also accommodate the reality that some people of the same gender genuinely loved each other and wished to live together.

20

The abolishment of

affrèrements

left a void for gay couples that would not be filled until civil unions—marriages in most legal aspects, without being called marriages—were sporadically recognized in the late twentieth century. In the intervening four hundred or so years, and especially during the religiously charged sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the nature of household relationships would become much more of a public business. Newly empowered state governments took on the responsibility of searching out sexual deviance wherever it occurred.

5

GROPING TOWARD MODERNITY: THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD, 1500–1700

D

URING HIS TWENTY-FIVE years on the throne of England beginning in 1660, Charles II missed few opportunities for sexual pleasure. He fondled women’s breasts in the theater, reached under ladies’ skirts in chapel, and took so many mistresses to his bed that he is credited with siring at least twelve illegitimate children. His court was a fireworks display of licentiousness. Behind every door, dukes, duchesses, ladies, and servants went at it with the vigor of caged beasts released into the wild. Even the argot of the court reflected this new burst of sexual freedom. The formerly shameful crime of adultery, for example, was now referred to using a French-based term of honor: “gallantry.” Engaging in dalliances became virtually prerequisite to attaining higher standing within the court. One hidebound lord who remained loyal to his wife was counseled to find a mistress immediately, lest he be “ill looked upon” and lose “all his interest at court.”

As Charles happily “rolled from whore to whore” with the “proudest peremptory Prick alive,” and the goings-on at court became source material for some of England’s first waves of popular pornography, all of English society reveled in a rediscovery of sexual gratification. After decades of Puritan austerity, the coronation of the rakish Charles marked the start of a more balanced approach to the regulation of pleasure. Under the Puritan influence that had held sway until then, serial adultery had been a crime punishable by death; cockfighting and horse racing had also been banned, theaters and brothels shut down, and alehouses harassed. By the end of the century, however, clerics were complaining that their parishioners were drinking, fornicating, and attending cockfights rather than honoring the Sabbath. The magazine

Town and Country

featured the landed elite’s sexual adventures, and English theater regained form with bawdy Restoration comedies. The court system run by the church, in which few sexual misconduct charges had ever been turned away, now waned in influence.

1

BACKLASH: THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION

Prior to the rise of Charles II, sexual restrictions could scarcely have been any tighter, in England or anywhere else on the Continent. The tumultuous sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth had witnessed a prolonged and violent face-off between Catholics and the upstart Protestants, in which both sides scrabbled for Christian souls. Increasingly religious states vied for bragging rights in piety, and tried, therefore, to micromanage sexual behavior as never before. The Protestant Reformation, ignited by the German priest Martin Luther in 1517 when he nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the door of a church in Wittenberg, had challenged every aspect of Catholicism, including its position on sex. To Luther, the Catholic Church was a moral sinkhole, and the pope a “shameless whore.” Catholics threw back ridicule at their Protestant rivals with equal zeal.

As states aligned themselves with one or the other side of the schism, Catholic and Protestant armies set forth to kill each other in vast numbers, along with civilian populations. As mutual hatred grew more intense, the kingdoms of Europe lurched into war during the early seventeenth century. Armed conflict and the elevated religious temperature made people increasingly suspicious and intolerant of each other. They expected their rulers take an active hand in regulating morality, which most were only too happy to do. The French theologian John Calvin spoke for nearly all Protestants when he declared that the purpose of government was to create “a public form of religion.” Individual sexual conduct thus became mainstream state business.

Protestants attacked Catholic morals as being too rigid in theory and too loose in practice. Luther derided the notion of priestly celibacy, just as he attacked the Catholic ideal of sexual abstinence as a whole. He was, indeed, correct in observing that few Catholic priests kept themselves away from sex: At least 95 percent of them in Bavaria had concubines, for example. But ridiculing clerical hypocrisy was just the beginning. Luther and other Protestant leaders turned the whole Catholic conception of sex and marriage on its head. To them, matrimony was not a concession to mankind’s innate sexual evil. Rather, sex was godly, and marriage a requirement for a good life. To forbid it to anyone, whether priests or farmhands, was to ensure earthly corruption.

Protestants accepted that sex was as essential to life as sleeping, eating, and drinking. If indulged in with “appropriate modesty” and in the marriage bed, it was “a sign of [God’s] goodness and infinite sweetness.” But while sex between husbands and wives was good, all other carnal relations were damned. On this there was no compromise. All adulterers, fornicators, and whores deserved nothing less than the gallows. In Puritan England and parts of Protestant Germany, adultery was a capital offense. As for prostitution, gone was the idea that brothels washed away filth from good society. Instead, prostitutes were seen (in Luther’s inimitable phrasing) as “scabby, scratching, stinking” and syphilitic monsters who deserved to be “broken on the wheel and flayed” or branded with hot irons. The men who patronized them were little better. City-run whorehouses, so common in the centuries before the Reformation, were now marked as particularly loathsome. Wherever Protestantism was adopted, official brothels were closed.

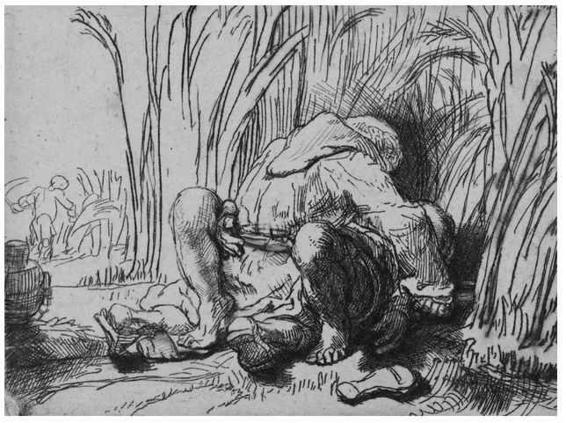

MONK IN THE CORNFIELD

During the Reformation, Catholics and Protestants commonly hurled sexual slanders at each other. The Catholic priesthood often got the worst of it, as Protestants attacked what they viewed as the myth of priestly celibacy. Here, a monk is depicted as taking unholy liberties with a woman in a cornfield.

©THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

In response to the Protestant challenge, the Catholic Church characteristically dug in its heels. In 1563, after a twenty-year conference known as the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church rejected every criticism Luther, Calvin, and the other reformers had thrown at it. Rather than concede the failure of requiring priestly celibacy, the Catholic Church strengthened its commitment to it. Far from abandoning the idea that abstinence was superior to sex, moreover, it now affirmed that virginity was in fact more blessed than marriage.

For the Vatican, sex stank as badly as ever, and with Protestants constantly accusing the Catholic Church of loose morals, it was time for it to prove its prudish mettle. Now, even masturbation drew intense Catholic condemnation. Some canonical writers cast it as a form of sodomy, worse than fornication or even adultery. One Catholic teacher focused his attention on “spontaneous” orgasms, i.e., those that occurred with no external stimulation. (Anyone who felt one coming on was told to lie still, make the sign of the Cross, and beg God to prevent the pleasure from reaching its peak.) Municipal brothels were closed as well, lest Catholic governments be accused of profiting from vice. Paris shuttered its brothels in 1556. Ten years later, the pope ordered Rome’s prostitutes to leave town—although that decree was annulled when authorities saw that twenty-five thousand people were preparing to vacate the city.

The repression of prostitution was part of a general lockdown on sex. European history had seen bursts of official prudishness before, but they were rarely so in line with popular sentiment. With all the screaming and Bible-thumping, the strict morality being preached everywhere was sinking in. We can never know exactly what people got up to behind closed doors or in the fields, but to judge by the decline in the number of illegitimate births and pregnant brides in France and England, for instance, it appears that there was less sex going on outside of marriage.

2

HEDGE WHORES AND BAWDY COURTS

The antipleasure principle in England also showed in people’s readiness to denounce each other to the courts for immorality. Many of these court cases were brought to secure advantages in other, unrelated quarrels, but that did not stop the courts from imposing humiliating punishments on the parties found guilty. Between 1595 and 1635, the number of immorality cases in the church courts more than doubled, sometimes comprising half their caseloads. With jurisdiction over “adultery, whoredom, incest,” and “any other uncleanness and wickedness of life,” there were no details of people’s lives into which the “bawdy courts,” as they came to be known, could not pry. In Essex County alone, adults had a one-in-four chance of being accused in a church court of sexual misconduct. Add to that the flood of sexual slander suits citizens brought against each other, and bucolic preindustrial Albion begins to look like a very unpleasant place. Quarrels and lawsuits were part of the firmament of village life, and nothing focused people’s attention more than a sex suit.