Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire (39 page)

Read Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire Online

Authors: Eric Berkowitz

The transition from religion to reason was patchy and disorderly. France decriminalized sodomy during its revolution—a giant advance in sexual freedom by any measure—but by 1806, England was still putting more sodomites to death than murderers. At the same time, while King George III was warning that divine wrath follows immorality, British publications such as

The Whoremonger’s Guide to London

brimmed with adverts for ladies of every description, talent, and price. Some brothels offered women of utmost refinement; others catered to men wanting to be whipped and choked in dungeons. There were paid shows featuring “spotless virgins” copulating onstage, and free peeks could be stolen of couples doing it in the streets and parks. (The rake and diarist James Boswell personally consecrated the new Westminster Bridge by having sex with a “strong jolly damsel” beneath it.) Sex was everywhere, in the open, and in the glow of the new philosophy of the Enlightenment it was natural, reasonable, and right.

The decline of religion sometimes took rather bizarre forms, as when Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris was converted into a “temple of reason” in 1793 (the year after the decriminalization of sodomy), and a showgirl was crowned “goddess” of reason and liberty at the cathedral’s altar.

1

In such cases reason became shorthand for hatred of the church and all it represented, but just as often, reason and science were co-opted to justify traditional Christian morals. The problem was that eighteenth-century science was often quite wrong—witness the panic over masturbation. In 1760, the respected Swiss physician Samuel Tissot published

L’Onanisme

, a blockbuster that characterized masturbation as a form of slow suicide. Tissot and his ilk blamed dozens of maladies on the world’s oldest pastime. Masturbation, they said, resulted in an irretrievable loss of semen, “the essential oil of the animal liquids.” If done with frequency, men were warned, sexual self-abuse depleted the body to the point of madness, illness, and death.

Tissot’s obsession with the subject started in 1757 after he learned of a young watchmaker who, the doctor said, masturbated as often as three times per day, resulting in a loss of semen so excessive the man grew fearful for his life. Tissot wrote that upon learning of the case he ran to the man’s bedside:

[W]hat I found was less a living being than a cadaver lying on straw, thin, pale, exuding a loathsome stench, almost incapable of movement. A pale and watery blood often dripped from his nose, he drooled continually; subject to attacks of diarrhea, he defecated in his bed without noticing it; there was a constant flow of semen; his eyes, sticky, blurry, dull, had lost all power of movement; his pulse was extremely weak and racing, labored respiration, extreme emaciation, except for the feet, which were showing signs of edema. Mental disorder was equally evident, without ideas, without memory . . . Thus sunk below the level of a beast, a spectacle of unimaginable horror, it was difficult to believe that he had once belonged to the human race.

Tissot arrived too late to rescue the patient and the experience rattled him deeply. He was already steeped in antimasturbation literature, and troubled by the weakness he had observed in his own self-pleasuring patients, but it was the sight of the watchmaker’s hideous state that brought out his true calling: “I felt then the need to show young people all the horrors of the abyss into which they voluntarily leap.” He sat at his desk and started to write.

What emerged was a book that used “science” instead of the Bible to justify old-time sexual repression. Masturbation not only violated God’s commandments, it was now labeled as medically harmful. Semen was stuff to be conserved, husbanded, and hoarded. Without an ample supply, the body slowed down and eventually stopped, as dozens of Tissot’s gruesome case studies supposedly showed.

L’Onanisme

was an instant hit and made Tissot famous and wealthy. The book quickly became a standard reference work and was translated into English, German, Italian, and Dutch. Tissot became the first major standard-bearer for the 150-year period ending just after World War I, which has been called the age of “masturbatory insanity.” A terrified masturbator wrote to Tissot in 1774: “Sir, you are the benefactor of mankind; please be mine as well.” The good doctor must have been only too happy to oblige.

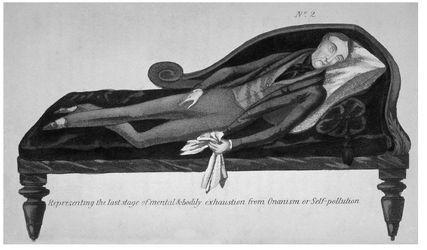

THE RAVAGES OF SELF-ABUSE

Starting in the eighteenth century and continuing for at least 150 years, prevailing science held that male masturbation wasted the body’s essential fluids, resulting in sickness, insanity, and sometimes death. This illustration, from 1845, depicts a man in the “last stages” of exhaustion from “self-pollution.” Meanwhile, sales of pornography were soaring.

© WELLCOME LIBRARY, LONDON

NOWHERE DID THE masturbation scare strike as hard as in Germany. A cadre of antimasturbation crusaders emerged, driven by the belief that increasing numbers of males and especially schoolboys were killing themselves. Everywhere they looked, they saw youths rubbing their crotches against trees, arousing themselves on horseback, and even stroking their privates in the classroom under long coats. Those boys who could not be frightened into stopping were sometimes put into mental hospitals or even infibulated—that is, their foreskins were tied shut over the head of their penis and held fast with iron rings. Later preventive devices, used everywhere, were no less crude. Right up to World War I, the U.S. government granted patents for contraptions that restrained, electrically shocked, and pierced penises with the temerity to become erect, even during sleep.

It is unclear whether many males were actually deterred from masturbating. In 1799, one influential German schoolmaster claimed success: “Thousands of young Germans, who ran the risk of ending their abject lives in a hospital, have been saved, and today devote their restored energies to the good of humanity.” That statement seems rather optimistic. Most boys and men, even if they were frightened at first, must have discovered that the horror stories simply didn’t pan out. Indeed, judging by the high consumption of pornography at the time, it appears that males everywhere were wasting their fluids in volume.

2

Most eighteenth-century masturbators did their business when no one was looking, of course. Not so among the five-hundred-odd members of the secret Scottish Beggar’s Benison society. Strict custom in the centuries-old club required initiates to sit alone in a room and obtain an erection while society members stood in a circle in a nearby chamber. Upon the blowing of a penis-shaped horn, initiates walked into the main room and placed their penises on a pewter “test platter” for the group to inspect and touch with their own genitalia. If all went well and the novitiate was approved, the group would welcome their new brother with the pledge “May your prick and your purse never fail you” and enjoy an evening of bawdy fun with prostitutes. To further cement ties among group members, the test platter and various silver receptacles would be brought out for them all to masturbate upon.

The men of the Beggar’s Benison society were respectable businessmen and magistrates. While they shared an interest in raucous drinking, whoring, and masturbating, their approach to their wives was quite another matter. Current mores encouraged the enjoyment of marital sex, but it was something to be managed along rational lines. For sober guidance in this regard, there were a number of manuals available throughout the United States and Europe, most notably

Aristotle’s Masterpiece

(published anonymously and having nothing to do with the Greek philosopher) and Nicolas de Venette’s

Tableau de l’amour conjugal

(

Conjugal Love

). These books, endlessly reprinted and cannibalized, picked up on the pseudo-scientific tone of the age to instruct married couples how, when, and why to make love.

Aristotle’s Masterpiece

went through forty-three editions by 1800.

Conjugal Love

was still in print in the 1950s.

De Venette echoed Tissot’s warnings about the dangers of excessive loss of semen, especially the risk of brain damage. At the same time, he taught that females demanded regular doses of semen to prevent their wombs from rotting and their minds from becoming frenzied. Both de Venette and “Aristotle” agreed that sex was required for a woman’s health. Even more important, unless a woman experienced orgasm during sex her own “sperm” did not flow and conception was impossible. It was therefore important for the husband to make sex pleasurable for the wife, so long as the goal was preparing her to conceive. (This belief also influenced rape law over the years, as judges often concluded that a pregnancy was proof that the woman enjoyed sex with the accused offender, and therefore no force was involved. See Chapter Four.) A later version of

Aristotle’s Masterpiece

also sets out some encouraging verses at the end of each chapter. Chapter Three, for example, provides the following thoughts for a newlywed husband to express to his panting wife:

Now, my fair bride, now I will storm the mint

Of love and joy and rifle all that is in’t.

Now my infranchis’d hand on ev’ry side,

Shall o’er thy naked polish’d ivory glide.

Freely shall now my longing eyes behold,

Thy bared snow, and thy undrained gold:

Nor curtain now, tho’ of transparent lawn

Shall be before thy virgin treasure drawn.

I will enjoy thee now, my fairest; come,

And, fly with me to love’s elysium;

My rudder with thy bold hand, like a try’d

And skilful pilot, thou shalt steer, and guide

My bark in love’s dark channel, where it shall

Dance, as the bounding waves do rise and fall.

Whilst my tall pinnace in the Cyprian streight,

Rides safe at anchor, and unlades the freight . . .

Perform those rites nature and love requires,

Till you have quench’d each other’s am’rous fires.

De Venette suggested that the man always be on top because that was the best position for conception. Other coital positions, such as woman-on-top, risked producing “dwarves, cripples, hunchbacks, cross-eyed or imbeciles.”

Aristotle’s Masterpiece

instructed the husband, after lovemaking, “not to withdraw too precipitately from the field of love, lest he should, by so doing, let the cold into the womb, which might be of dangerous consequence.” The wife should sleep on her right side and avoid coughing, sneezing, or even moving. Intercourse was to be repeated “not too often,” otherwise the husband would “spend his stock” before conception was achieved.

The sex manuals’ focus on reproduction excluded other kinds of lovemaking. Pleasure for its own sake had no place in the biologically balanced marital chamber. Yet fewer people than ever were living their lives that way. Sex, conjugal and otherwise, was increasingly seen as part of the natural order of the world, like the tides, and it was happening everywhere in every possible permutation. The law’s task was to balance the weight of fifteen hundred years of restrictive moral teachings with society’s carnal demands. The results were anything but neat.

3

FEMALE LOVE AND LEATHER MACHINES

Can two women love each other sexually? Eighteenth-century morals said no, at least where the females involved were respectable. Among the better classes, lesbian relations were impossible to imagine. Good women could love and embrace each other, sleep together, and write each other passionate letters; all that was noble. But loving and making love were entirely different matters. Unless they were gratifying their husbands, women of “character” were imagined as sexually numb creatures. British judges allowed that females of “Eastern” or “Hindoo” nations might act differently, but not the women of the “civilized” world.

When Marianne Woods and Jane Pirie, the unmarried comistresses of a tony Scottish boarding school for girls, were accused in 1811 of “improper and criminal” conduct with each other, every single student in the school was removed by their parents. Woods and Pirie were ruined overnight. Their primary accuser was a student, the Indian-born grandchild of Dame Helen Cumming Gordon. The girl, who had shared a bed with Miss Pirie, told Dame Gordon that she had been woken up by Miss Woods climbing on top of Miss Pirie and “shaking” the bed. “Oh, do it, darling,” Miss Pirie reportedly said as they rolled around together in “venereal” bliss. The girl further reported that the two women cooed as their bodies made the sounds of a “finger [in] the neck of a wet bottle.”

Dame Gordon sent out letters telling parents that their children were in “grave danger,” and that was it for the school. Pirie and Woods filed a libel suit against Gordon to recover their lost life savings, if not their reputations. Hundreds of pages of trial transcripts later, the two women won, not because they did not sleep together or love each other intimately—they did—but because the judges could not accept that two hardworking, middle-class women such as these could possibly have had sex with each other.