Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire (42 page)

Read Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire Online

Authors: Eric Berkowitz

The scapegoat was the gentleman Benjamin Deschauffors, who was burned alive in Paris for, among other things, selling boys to French and foreign aristocrats and running a “sodomy school.” More than two hundred people were implicated in the Deschauffors affair, including a bishop who was banished to his seminary and the painter Jean-Baptiste Nattier, who cut his own throat in the Bastille while awaiting trial. The majority of those accused received jail terms of a few months. Yet if the police hoped that a rare execution would deter others who were “infatuated with the crime against nature,” they were very wrong. Paris continued to host more than its share of homosexual action, especially in the Tuileries and Luxembourg Gardens, the city’s taverns, and the libertine wonderland that was the Palais-Royal. At least one-third of the men caught by police were married.

By 1750, only three additional men had been put to death for sodomy, two of whom had been caught in the act. If the lives of sodomites were relatively safe, though, their overall legal status remained precarious. The Deschauffors affair was enough to keep people on their toes, especially those with no money or connections. By the 1780s, a special Paris police division was conducting nocturnal “pederasty patrols.” Commissioner Pierre Foucault kept a list, in a big book, of tens of thousands of suspected sodomites—as many, he claimed, as there were female prostitutes in the city. The patrols’ nightly catches could be as mundane as hauling in a haberdasher for sticking his hand down the pants of a wig-maker during a public execution, or as colorful as an orgy bust in the Palais-Royal. They all went into the book.

By 1791, as the French Revolution raged and King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette languished in jail, the Constituent Assembly approved a new set of criminal laws that omitted any mention of sodomy and sins against nature. Thus a crime was erased on the books, but not in the minds of many of the people—including the police. The next century would see the heavy use of laws against public decency to harass those engaging in homosexual sex.

11

VIRGINS AND VD

Venereal diseases had everything to do with the way the law dealt with sex, especially sex for money and sex by force. Current thinking held that “good” girls didn’t pass on sexually transmitted diseases; only the “bad” ones did. Men were innocent victims. “[M]en contract this evil from women that are infected,” according to one medical source, “because in the [sex] act . . . the Womb being heated, vapors are raised from the malignant humors in the womb, which are suck’t in by the man’s Yard.” In this way, held another authority, “the Pocky Steams of the diseased woman do often evidently imprint their malignity on the genitals of the healthy play-fellows.”

The pain and embarrassment of venereal disease, especially syphilis, made people desperate for a solution. The dozens of “cures” available for purchase, such as mercury injections, were often as dangerous as the disease itself. Among the remedies, many agreed that one was superior: intercourse with a young virgin. In London and elsewhere, men sought to cleanse their “pocky” members in the pure fluids of prepubescent girls. Brothels profited by this “defloration mania” by touting purportedly untouched girls. The same girls were sold as virgins time and again, often with “patched up” maidenheads and little blood pellets strategically placed in their vaginas. However, customers with even a little common sense must have known they were not really getting what they paid for. Only truly innocent little girls would do, and to get at them force was usually involved. From 1730 to 1830, at least one-fifth of the capital rape cases in London’s Old Bailey involved young children. While the rapists’ motivations were not always clear, many were at least in part trying to cure themselves of sexual diseases. The courts never accepted this as a defense, but that did not stop people from believing it to be true.

Consider James Booty, who had raped five or six children less than seven years old by the time he himself turned fifteen. Shortly after being infected by his cousin, a friend told him that “a man may clear himself of that distemper by lying with a girl that is sound.” Booty went after every little girl within his reach, including his master’s five-year-old daughter. His master had the money and the motivation to push through a prosecution, and Booty was executed, but that result was not typical.

English law never gave much of a hoot about protecting small girls from sexual predators. The traditional age of consent for females was ten, well before the arrival of puberty for most—which allowed men to develop a taste for tender girls. Said one libertine in 1760: “The time of enjoying immature beauty seems to be the year ’ere the tender fair find on her the symptoms of maturity”—that is, before menstruation “stained her virgin shift,” and while “her bosom boasts only a general swell rather than distinct orbs.” This fetish for taking virgin children became widespread and was, at least tacitly, tolerated.

If a child rape case did make it into court, there was a four-in-five chance the assailant would be acquitted, because the law required proof that the sex had been forced, and that the man had ejaculated inside the victim. Practically, that meant that immediately after a child was raped she had to have the presence of mind to find someone reputable who would, in effect, violate her again to obtain critical evidence. Given that the victimized girls were usually brought down by terror, shame, and physical pain, the reality was that they were there for the taking. Even when there

was

proof of rape, the high cost of a trial effectively slammed the courthouse door in the victims’ faces. In one case, the nine-year-old daughter of a servant woman named Margaret East was raped and infected by a man East had trusted. When East could not pay the medical examiner’s fees, the examiner hired himself out to the rapist and testified that the girl’s hymen was still intact. The man was acquitted.

IN THE UNITED States, a man’s social position also protected him against a rape conviction. The 1789 diary of Martha Ballard, a rural Maine midwife, bears haunting witness: Ballard’s neighbor, Rebecca Foster, told her that several men had “abused” her since her husband Isaac, a pastor, had left the area on business. One of the abusers was Joseph North, a local power broker, who had broken into Foster’s house and treated her “wors [

sic

] than any other person in the world had.” Foster sought Ballard’s counsel. “I Begd her never to mentin it to any other person,” wrote Ballard. “I told her shee would Expose & perhaps ruin her self if shee did.” Foster rejected Martha’s advice and told her husband Isaac about the incident. The pastor then took the extraordinary—and risky—step of suing North for the rape.

The trial took place in the tiny river town of Pownalboro. The judges sailed upriver from Boston to the courthouse, as they did twice a year, with valises full of powdered white wigs and black robes. Ballard, who was called to testify, took a boat downriver to Pownalboro—her first visit there in twelve years. The drama was high. Rape cases were rare, and any woman who accused a powerful man of the crime could expect a withering counterattack. Ballard’s diary recorded “strong attempts” at trial “to throw aspersions on [Foster’s] Carectir.” Although it was not spelled out, there is little doubt that North’s lawyers would have accused Foster of entertaining men while her husband was away. The matter was further complicated by the fact that Foster had delivered a baby almost nine months after her encounter with North. Most likely, North’s “aspersions” of Foster included the charge that she was trying to force a wealthy man to support someone else’s child.

On July 12, 1789, North was acquitted, “to the great surprise of all that I heard speak of it,” according to Ballard. The Fosters and their children left the area for good and settled in Maryland until Isaac’s death in 1800. Rebecca then went to Peru with her youngest son to prospect for gold.

12

LOVING THE LASH

Samuel Self underestimated his wife Sarah when he sued her for divorce. The Norwich bookseller thought he had a good plan. He had trapped Sarah and her lover, John Atmere, in flagrante delicto, so the court would likely let him out of the marriage without having to pay her anything. Never, he thought, would she have the cheek to strike back by revealing the continuous group sex, erotic whippings, and impromptu sexual shows they had both been hosting in their house for several years. But she did—and by the time the legal proceedings were over Samuel and Sarah were both ruined.

The marriage had never been a healthy one. Samuel was still a virgin at their wedding in 1701, and within a few weeks Sarah had given him gonorrhea. Soon after that she was climbing uninvited into the bed of married neighbors, proposing ménages à trois and presenting a tuft of her maid’s pubic hair as a gift. Whether Samuel was aware of Sarah’s late-night wanderings isn’t known, but by 1706 his own sensibilities were no longer innocent. With the active assistance of Atmere, their maid, and some lodgers, the Self house had become a freewheeling swingers’ club, in which sexual partners were traded and whipped each other silly while the others watched.

The most common element of the orgies at the Self house was group flagellation, usually involving Samuel taking a lash to a lodger, Jane Morris. According to the court, Samuel had “indecently, immodestly, lewdly and incontinently” abused Morris “by turning up her clothes and whipping her bare arse, with rods . . . fit instruments for [his] awkward lewdness and devious incontinence.” Morris was often held down by others in the house while Samuel gave her a whipping. Each application of the lash brought Samuel to a new level of excitation, so much so that on several occasions he threw the lash down, grabbed his wife, and begged Atmere to whip her.

This was all confusing for the court, and delightful for Norwich’s gossipy townspeople. The proceedings dragged on for two years, each new sworn deposition adding a lurid splash of color to the picture. What was the court to do? Given the Selfs’ perversions—he an obsessed whipper, she an all-purpose party girl—how could the court judge one more worthy than the other? It was not easy, but judging is what courts must do. Despite the evidence that Samuel was an adulterer himself, the divorce was approved, and Samuel was not compelled to pay alimony, but after two years of court action Samuel’s reputation among the respectable folks of Norwich was ruined. His book business fell apart, and in 1710 he was arrested for passing bad financial paper. As for Sarah, she was left homeless and broke.

The Selfs’ penchant for whipping was “gross and unnatural” to the court, but it was not atypical. Flogging, both as punishment and as sex play, was common, and most courts were reluctant to penalize it. In 1782, one judge ruled that a man may beat his wife without legal consequence so long as the stick was no thicker than the width of his thumb. The court was referring to discipline, but the line between punishment and prurience is not always clear. Jean-Jacques Rousseau spoke for many of his contemporaries when he wrote, in his

Confessions

, that he grew to love whippings as a child: “I found in the pain, even in the disgrace, a mixture of sensuality which had left me less afraid than desirous of experiencing it again.” For the rest of his days, Rousseau wanted to be whipped.

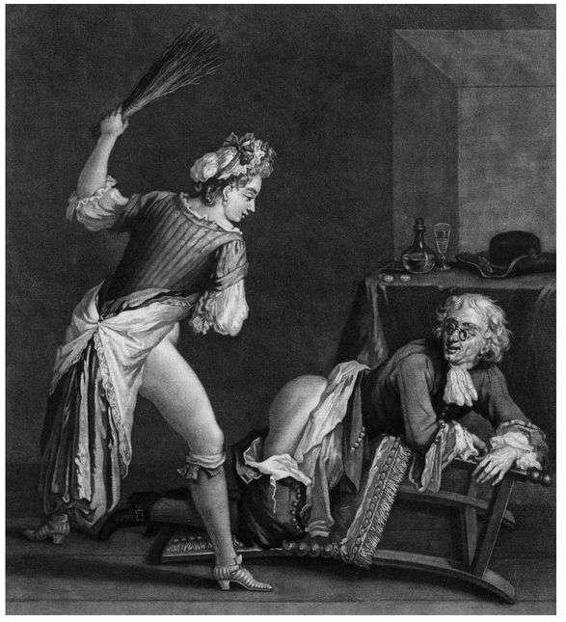

Whipping skills were part of any good prostitute’s repertoire. The newspapers were filled with advertisements for brothels offering a good flog. William Hogarth’s famous 1732 series of engravings,

A Harlot’s Progress

, depicts, among other scenes, a prostitute in her boudoir with a collection of birch rods close at hand. One madam later employed a specially crafted flogging machine onto which she strapped her customers, while another machine administered whippings in industrial volume by accommodating forty men at once.

THE PLEASURES OF THE BIRCH

The British loved their flogging. Whipping skills were part of any good prostitute’s repertoire and domestic violence was generally tolerated by the courts, unless it reached “gross and unnatural” proportions.

©THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

The Selfs’ divorce trial roughly coincided with a burst of new pornography devoted to the pleasures of the birch. To choose just two examples, the reprobate publisher and bookseller Edmund Curll did well with the quasi-scientific

Treatise on the Use of Flogging

, while John Cleland’s monumental erotic novel

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (Fanny Hill)

devoted much space to the practice. Cleland describes, in loving detail, the prostitute Fanny Hill’s harsh treatment of a man she ties to a bench with his own garters. Once she has reduced his “white, smooth, polish’d” buttocks to a “confused cut-work of weals, livid flesh, gashes and gore,” Fanny offers up the “trembling masses” of her own “back parts” to the man’s “mercy.” At first he uses the rod gently, but after a few minutes, “He twigg’d me so smartly as to fetch blood in more than one lash: at sight of which he flung down the rod, flew to me, kissed away the starting drops, and, sucking the wounds, eased away a good deal of pain.” Miss Hill finds the experience to be disconcerting at first, but after a glass of wine the “prickly heat” of her wounds puts her into a state of “furious, restless” desire for traditional sex. Her partner gladly obliges.

13