Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm (12 page)

Read Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm Online

Authors: Rene Almeling

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Medical, #Economics, #Reproductive Medicine & Technology, #Marriage & Family, #General, #Business & Economics

It is certainly the case that egg agencies and sperm banks have different business models. Egg agencies are essentially brokers, matching donors and recipients before sending them off to medical professionals for tests and procedures. In 2002, both OvaCorp and Creative Beginnings

charged recipients an agency fee of $3,500 for these services and then added standard fees for the donor’s medical and legal expenses. The egg donor’s fee is a separate line item on the bill, and the agency receives no additional compensation for negotiating a higher fee for her. If recipients experience a “failed cycle” with a donor, the staff might offer a discounted rate on the second cycle. In some cases, staff will even explain the situation to the egg donor and ask her to accept a lower fee.

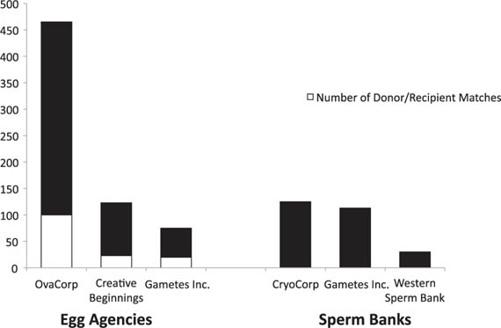

Figure 3

. Number of egg and sperm donors with posted profiles, by program

Sperm banks are much more than brokerages in that they have labs for testing sperm samples, storage facilities for freezing thousands of vials in nitrogen tanks, and shipping departments for managing distribution. In 2002, the nonprofit Western Sperm Bank paid men $50 for each acceptable sample, and the for-profit CryoCorp paid $75. Acceptable samples can generally be split into several vials, from two or three to as many as eight or nine. Each vial is then sold for $175 at Western Sperm Bank and $215 at CryoCorp.

18

Undoubtedly, the different business models contribute to the different prices in this market.

Another consideration for an analysis of supply and demand is the unexpected finding that sperm donors are relatively difficult to recruit, yet egg donors sign up en masse. With very little advertising, OvaCorp

receives around one hundred applications a day, and Creative Beginnings receives several hundred inquiries every month. In stark contrast, CryoCorp maintains three locations in different parts of the country and employs several people whose entire job description revolves around donor recruitment. Moreover, both sperm banks pay current donors hundreds of dollars in “finder’s fees” if they refer applicants who are accepted into the program. Discussing his experience running a sperm bank, the founder of Gametes Inc. explained,

For a substantial part of our history, donor recruitment was a major concern, having an aggregate number of donors plus donor diversity. We just couldn’t keep inventory to meet the demand. Not that we were growing hugely. You’d think if you didn’t have enough inventory to meet demand, then you could name your own price and just be fabulously wealthy. Well, it didn’t work out that way.

To increase the supply of sperm, Gametes Inc. opened offices around their small Southern town. In doing so, according to the founder, they were “taking a page from financial bankers who have branches on every corner. You’d think convenience would be a major asset. Well, most guys don’t want people knowing that they’re masturbating, so having a neighborhood branch where mom and dad can see what you’re doing isn’t really cool [

laughs

].” Over the years, the program opened offices in a nearby university town, in a large city a few hours away, in a nearby state, and in Canada. But now, it maintains just two offices: “headquarters” in the same small Southern city where the program started and a satellite office in a large city two hours away that is close to several major universities. To this day, Gametes Inc. must advertise constantly for sperm donors, and program staffers routinely remind men to send in their friends.

It is striking that the difficulty in recruiting men does not produce an increase in their compensation and the apparent oversupply of women has not caused their fees to drop. Two popular conceptions—that most men would jump at the chance to make some extra cash by selling their sperm and that it is difficult to find women willing to undergo shots and surgery for $5,000—simply do not hold. Indeed, between 2002 and 2008, the number of profiles listed on OvaCorp’s website more than doubled.

The program now has more than a thousand women available to donate, yet recipients are still informed that egg donor fees will be between $5,000 and $10,000.

In this stage of the process, a donor’s attributes, encapsulated in the profile and extolled by staff, are used to generate income for the programs through matches, but the economic valuation of women’s eggs is more intimate than that of men’s sperm. Women are paid to produce eggs for a particular recipient who has agreed to a specific price for that donor’s sex cells. At the same time, staffers tell recipients the “donor would love to work with you,” and they inform egg donors that the recipients just “loved you and had to have you.” Thus, egg agencies structure the exchange not only as a legalistic economic transaction, but also as the beginning of a caring gift cycle, which the staff members foster by expressing appreciation to the egg donors, both on behalf of the agency and the agency’s clients.

OvaCorp’s donor manager explained, “We have the largest donor database. The reason is we treat them like royalty. They are women, not genetics, to us. A lot of times a couple doesn’t meet them, so we want them to feel our warmth, feel the reality that we’re so grateful for what they’re doing for us as well as because they’re making our couple happy.” Likewise, CryoCorp’s marketing director notes, “We have to walk that tight-rope and make sure the [sperm] donors are happy, because if we don’t have happy donors, then we don’t have a program, and yet make sure the clients are happy as well [

laughs

]. So we’re always mindful of that.” But in sperm banks, being a “happy donor,” whose sex cells are purchased by many different recipients months after he has produced them, is not predicated on being placed in the position of “loving” and “being loved by” extremely grateful “future parents.”

FRAMING PAID DONATION AS A GIFT OR A JOB

Programs screen applicants for “responsibility,” and staff must carefully monitor donors as they fulfill contractual obligations to produce eggs and sperm. Egg agency staffers are always on the phone with donors

and doctors to find out when women begin menstruating, start fertility shots, miss doctors’ appointments, and schedule egg retrievals. Creative Beginnings’ founder explained, “Most of the donors are very conscientious, and especially our donors, because we look for girls who are going to be compliant and do things right.” To maintain “inventory,” sperm bank staffers are continually assessing which donors miss appointments, register unusually low sperm counts, or need blood drawn for periodic disease testing. According to a donor screener, Western Sperm Bank must be vigilant because donors “are creating a product that we’re vouching for in terms of quality control.”

If an egg donor is not currently available, as is the case with many of the most popular donors, then an egg recipient can “reserve” her for a future cycle. If a sperm donor’s vials are “sold out” for that month, recipients can be placed on a waiting list. Sperm recipients also have the option of creating a “storage account,” in which they buy multiple vials of a particular donor’s sperm to guarantee its availability if they do not become pregnant during initial inseminations. In explaining this system, CryoCorp’s marketing director blurs the line between the donor and the donor’s sperm when she discussed the bank’s “inventory.”

We do limit the number of vials available on any given donor by limiting the amount of time a donor can be in the program. All of our specimens are available on a first-come, first-serve basis. We are dealing with human beings here, and the donors have finals and they don’t come in. And they go away for the summer. So our inventory is somewhat variable. So we suggest [recipients] open a storage account, which just costs a little bit additionally, and then purchase as many vials as they want.

In each of the four programs, staffers identify the donor’s responsibilities as being like those in a job, but in the case of egg donation, it is understood to be much more meaningful than any regular job. At an informational meeting for potential egg donors, Creative Beginnings’ founder explained, “You get paid really well, and so you have to do all the things you do for a normal job. You have to show up at the right time and place and do what’s expected of you.” Her assistant added, “If you really simplify the math, it’s $4,000 for six weeks of work, and it’s maybe

a couple hours a day, if that. And to know that you’re doing something positive and amazing in somebody’s life and then getting compensated for it, you can’t ask for anything better than that.” Agency staffers simultaneously tell potential egg donors to think of donation “like a job” while also embedding the women’s responsibility in the “amazing” task of helping others.

Contact between staff and donors does not necessarily end on the day of the egg retrieval or when sperm donors provide their last sample. Sperm donors must return to the bank for HIV testing six months after they stop donating, and men who agree to release identifying information to offspring must update their addresses with the bank indefinitely. If an egg donor performs well in her first cycle, then the agency will hope to match her with future recipients. However, OvaCorp’s donor manager is careful not to ask a woman too early about another cycle. She explained, “If it’s a first-timer, I won’t ask her to do it again until she’s cleared the cycle, because I don’t want her to think I’m being insistent upon a mass producer. I’ll say, ‘There’s another couple that would love to work with you. However, let’s just concentrate on this one couple that we’re talking about.’ ”

But women who attempt to make a “career” of selling eggs provoke disgust among staff, in part because they violate the altruistic framing of donation. Egg agencies generally follow ASRM guidelines limiting women to five cycles, recommendations that are designed to minimize health risks. However, it is not concern for the woman’s health that the OvaCorp donor manager expresses in this denunciation of one such “career” egg donor. “She’s done this as a professional. It’s like a career now. I said, ‘There’s something about that girl.’ Then I called [the director of another egg agency], and she’s like ‘oh yeah, why’s she calling you? I won’t work with her anymore; she worked with me eight times.’ I said, ‘Eight times?! She’s got four kids. She’s on the county. Yeah, I remember that name.’ ”

In sperm banks, the decision to limit men’s donations centers on the goal of efficiently running a business without offending the sensibilities of the bank’s clients. CryoCorp’s CEO explained,

There’s an ongoing debate of how many vials should you collect from any one donor. If you have 10 donors and collect 10,000 vials from all of them and you have to replace 1 [donor because of genetic or medical issues], it’s taking a hit to your business. If you wind up with 10,000 donors and only collect 10 vials from every single one, you’re inefficiently operating your business. You need to figure out what that sweet spot is. But then there’s the emotional issue from a purchaser. If a client knows that, with X thousand vials out there, there could be 100 or 200 offspring, what’s that point where it just becomes emotionally too many? With my MBA hat on, we are not collecting enough vials per donor, because we’re not operating as efficiently as we should. With my customer relations/consumer hat on, we’re collecting the right number of vials, because clients perceive that it’s important to keep that number to something emotionally tolerable. At what point do you say that’s just not someone I want to be the so-called father of my child, because there’s just way too many possible brothers and sisters out there?

Given the extensive investment required to screen gamete donors, one would expect programs to gather as much reproductive material as possible from each person. Instead, women are discouraged from becoming “professional” egg donors, and men are prevented from “fathering” too many offspring.

In keeping with the focus on altruism in egg donation, both OvaCorp and Creative Beginnings’ staffers encourage recipients to send the donor a thank-you note after the egg retrieval. This behavior is not present in the sperm banks. In many cases, egg recipients also give the donor flowers, jewelry, or an additional financial gift, thereby upholding the constructed vision of egg donation as reciprocal gift giving, in which donors help recipients and recipients help donors. Creative Beginnings’ founder explained that if recipients ask her “about getting flowers for the donors, I ask them not to do that, because flowers get in the way. The donor’s sleeping, and she’s not thinking about flowers. If you want to get a gift, get a simple piece of jewelry, because then the donor has something forever that she did something really nice.” This rhetoric even shapes accounting practices; although most programs inform donors that they will be sent a 1099 tax form, which is designed for independent contractors providing a service, one of the egg agencies considers the donor’s fee a nontaxable “gift” from the recipient.

The most extreme case I heard of postcycle giving was reported by OvaCorp’s donor manager.

Donor Manager: I paid a donor $25,000. That’s only because it was $10,000 for the donor’s fee, and then when their kids were born, they gave her an additional gift of $15,000.