Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm (19 page)

Read Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm Online

Authors: Rene Almeling

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Medical, #Economics, #Reproductive Medicine & Technology, #Marriage & Family, #General, #Business & Economics

There is much less variation in what men are paid per donation, with most banks offering the same flat rate to all donors. This was set at $50 at the nonprofit Western Sperm Bank and $75 at the for-profit CryoCorp in 2002. Gametes Inc. has a two-tiered system, paying anonymous donors $65 and identity-release donors $100 per sample in 2006. But even these slight differences in rates combine with variation in how often men donate to create a wide range of earnings among sperm donors. Staffers encourage men to make weekly deposits (at least), but some donors choose to donate two or three times a week. It is very common for samples not to pass, though. So men who make $50 per sample and donate (and pass) one sample each week will make $200 in a month, and those who make $100 per sample and donate (and pass) three samples each week can make as much as $1,200 in that time.

Inevitably, sperm banks trumpet the highest amount possible in their advertisements, but donors rarely achieved this level of income on a regular basis. Four men who were paid $50 per sample at Western Sperm Bank reported earning between $250 and $500 per month (average: $375). Seven identity-release donors who were paid $100 per sample at Gametes Inc. reported earning between $600 and $1,200 per month (average: $930). Moreover, an individual donor’s earnings could fluctuate quite a bit from month to month. For example, Victor, a twenty-three-year-old identity-release donor at Gametes Inc. referred to himself as a “full-time donor” because he makes three deposits each week. “Usually my samples make it. Sometimes I may have had a bad week, and two samples didn’t make it. So, I’m saying anywhere from $360 to $540 every two weeks.” Victor’s calculations are based on multiples of $90, because Gametes Inc. is the only program to withhold $10 from each passing sample as an incentive to the donor to show up for periodic blood tests. If the donor passes the tests, the accumulated money is disbursed.

About half the women who lived in metropolitan areas applied to multiple programs, either to increase their chances of being chosen by a recipient or because they were rejected by the first program they contacted. Sperm donors were less likely to engage in this behavior both because there are fewer sperm banks and because of the more intensive time commitment. For example, Andrew, who was in graduate school,

did look into another program that was about forty-five minutes away. That program paid $75 or $100 compared to the $45 he received when he first signed on with Western Sperm Bank, but he did not want donation “to be a huge time commitment. Western Sperm Bank is close to where I work, so I can stop in a couple times a week and work it around my work schedule.”

Just as egg and sperm donors express similar motivations for donation, they spend the money on similar things. It is “special money,” in that it is earmarked for particular purposes; just 5% of the donors did not have a specific plan for it.

8

A few donors, including two divorced mothers of young children and four single men working multiple low-wage jobs, did use the money to cover basic living expenses. But most donors did not portray their financial situations in such dire terms. About half used at least some of the money to pay off debt, as did Dana.

The first time I had a retrieval, I was only paid $3,500, and I used it to pay off bills [

laughs

]. I’d gotten out of college and didn’t have anything, so I had to buy furniture, this and that, and I got it all on credit. So I just paid a lot of that off and then bought stuff for my house that I own now. Every other time since, I’ve gotten 5,000 [dollars]. [The second retrieval] was paying off some more bills and just kind of doing stuff around the house. [The third retrieval] was to pay off Disney World tickets [

laughs

] that I put on my credit card, and I bought a vehicle. I put a big down payment on an [SUV]. The [fourth retrieval], I paid off bills from my wedding [

laughs

]. So, I’ve really accomplished a lot with the money.

Egg donors were more likely to use at least some of the money for school, either by paying for tuition or by paying off student loans. Samantha worked full-time as a clerk while also going to college. She attended a community college for two years before transferring to a state university, where she took twenty credits per quarter and went to summer school in order to graduate in one year. The money from egg donation was “exciting because that would go toward school. I’m trying to pay for school myself, so that was like a really big help. I just put it in savings, and I didn’t really touch it. Then, each quarter, when they send the billing account, I’d take from it and pay for it that way. When I was almost done with school, which wasn’t too long ago, then I put the rest,

almost, not all of it, the rest toward my car.” Budgeting such large payments is probably made easier by the fact that egg donors’ compensation comes in the form of one lump sum.

In contrast, sperm donors are paid every few weeks, and they were more likely to classify the money as “expendable income.” For example, Fred, a fraternity brother, used it to buy alcohol and food on weekends. Paul, another undergraduate, put what he earned from his other part-time jobs into savings and directed the money from sperm donation to “groceries and gas and usually a little something extra, a shirt or something every few weeks.” Just one of the sperm donors diverted the money to educational expenses. Either men’s parents paid for school, or they qualified for a state scholarship.

Several of the younger women and men suggested that earning money as donors made them more financially responsible. Mike, a twenty-two-year-old with credit card debt from when he was a teenager, described paid donation as “a way for me to be that guy that always pays his bills. It’s just helped me grow and become more responsible as a person, rather than just sitting around, scrounging around for money, trying to get it waitering or doing whatever else I’d have to do to make it. It’s just makes me more financially responsible.” Jane, the daughter of financially struggling immigrants and a student at a prestigious university, had already completed three cycles with Creative Beginnings before turning twenty. She said, “Being an egg donor, I’m earning my own money. I’m trying to take care of myself. It makes me a little more independent.”

Donors who were initially motivated by the idea of helping recipients were more likely to save the money from donation or use it to buy extras for themselves or their families. Lisa, a music teacher, described the money from egg donation as “gravy.” She used the fee from her first cycle to buy a vintage car, which she planned to repaint with the fee from her second cycle. Travis, an engineer with an MBA who was not dating anyone at the time, kept his earnings in a special “kitty.” He said that his family was both religious and conservative, and he had not disclosed his activities at the sperm bank to them. His own ambivalence about the money and how he was making it is evident in how he managed it.

Travis: I cash the checks, don’t put them in the bank, and I just put them in this thing. I use a little bit for extra cash from time to time, but by and large, I’m just kind of saving it right now. I’ve thought about different things. Well whenever I get married or engaged, I’ll use that money to buy an engagement ring. So it’s kind of like—I don’t want to say turning the bad to good—but kind of like using something that wasn’t, that was for something else. What am I gonna do with this money every week? I don’t want to have nothing at the end of the day or year that I’ve got to show for this. I’ll just put it away and use it for something. I don’t know what.

Rene: That’s so interesting because you’re an MBA, and you would presumably know everything about accounting, that you would have a little, almost Depression Era

—

Travis: [

laughs

] Exactly. With every other penny I make with my regular income, I have investments and planning, and I own a house and all this stuff. I’ve got all that allocated, and that’s why with this, it’s just kind of hiding money under the mattress. Everything else is so structured. This has no purpose, no direction. This is just a little savings stockpile, rainy day, something. I mean, I’ve got rainy day money, but this is just kind of different. I don’t know.

Rene: Do you know how much is in there?

Travis: No, I have no idea.

Scott, a married professional, categorized the income from sperm donation as “just play money,” which he spends on extras for his three kids.

It doesn’t generally even hit the books the same way. I mean the other [paychecks from our jobs], automatically in, and we’ve already got it set up to pay bills. Overall household income, [the money from sperm donation] doesn’t impact it that much, but it does give us a little extra so that we can do the stuff that we want to do with the kids: Six Flags season passes. That kind of stuff we wouldn’t be able to do if we didn’t have that.

Donors who treated themselves were generally single without children, and those who bought extras for others were usually in serious relationships and/or had children.

BEING PAID TO GIVE A GIFT OR PERFORM A JOB

Women and men sign on to donate for similar reasons, and they spend the money on similar things, so it would follow that they would talk about this activity—being paid to produce sex cells—in similar ways. But in fact, this is not the case. Women portray donation as a gift, while men consider it a job, rhetorical variation that maps directly onto the gendered organizational framing of donation in egg agencies and sperm banks.

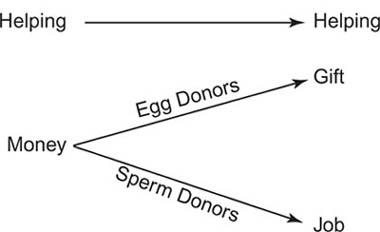

Donors’ trajectories, from their initial interests in donation to how they come to define what kind of activity it is, are presented in stylized form in

Figure 4

.

9

The few donors whose initial interest was sparked by the prospect of helping recipients have children remain committed to this goal. However, those who were initially motivated by money eventually adopt different ways of conceptualizing donation, with women making use of gift rhetoric and men relying on employment rhetoric.

10

Only one man called donation a gift, and just three women said it was a job. Two of these three women did so while explaining how they originally thought of donation as a job but now think about it in terms of helping recipients.

Throughout the donation process, as women interact with staff, and occasionally with recipients, they hear over and over that egg donation is a gift. In fact, women often encounter this framing in their very first contact with programs, either through advertisements or through conversations with donor managers. Kim, a recent college graduate whose “whole intention of getting this extra money is getting out of debt,” had been matched with a recipient, but she had not yet donated. I asked when she first learned about the compensation.

Well, of course right up front. The way [OvaCorp’s donor manager] explains it, it’s so cute. “It’s a gift; it’s a gift” [

singing and laughing

]. She’s like, “You’re giving a gift, and you just deserve to get something in return for it.” It sounds so not like, I guess when you just think of it, it’s just ah I’m getting money, but she makes it sound like it’s a gift. Very cute.

Describing a similar message from Creative Beginnings, Megan went to the donation program’s information session thinking “the biggest [stereotype] for me was that you could do [egg donation] as many times as you wanted to, that you could profit on basically selling body parts. At the meeting, I learned it’s more like a blood donation and a Good Samaritan deed.”

Figure 4

. Donors’ initial interests in and current conceptualizations of paid donation

The recipient of this gift does not remain an abstraction, because staffers regularly spend time communicating who recipients are and why they are pursuing egg donation. Such information can have a powerful influence on how women think about donation. Carla, a twenty-five-year-old college student with a young child, detailed how her initial formulation of donation as a “second job” began to change during her very first conversation with the founder of Creative Beginnings, whom she spoke with after seeing an advertisement in a local parenting magazine.

Rene: What made you stop and look at the ad?

Carla: Well, definitely the $5,000. That’s why they put it there in bold print. It’s like, okay, I’ll call. Then after finding out about the procedure, going home, talking to my husband, then it was more than just the money. It was safety issues and stuff like that. You go through all the pros and cons. Is it worth it? At that point, it became less of the money and more understanding the recipient, why they’re going through all this trouble. They’re spending a lot of money. Besides just what I get, there’s all the doctor bills and procedures; she has to carry the eggs. That’s what these people are going through. The only way I could relate to that was before I had my son: we were trying to get

pregnant, so it was the anxiety, the anticipation, the peeing on the stick. I didn’t have any difficulty getting pregnant, but even the one month, oh my God, I’m a day late, then it’s negative, and just kind of being bummed out, remembering that feeling and sort of correlating it to what they’re going through. So I gotta give it to them. I gotta help them.