Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm (17 page)

Read Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm Online

Authors: Rene Almeling

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Medical, #Economics, #Reproductive Medicine & Technology, #Marriage & Family, #General, #Business & Economics

Like Kyle, Ryan, a forty-year-old who had been donating once a week for the last several years, referenced the money in discussing how he smoothed over the issue of abstinence with his wife, calling it a “peace offering.”

None of the egg donors mentioned male partners complaining about abstinence, but several sperm donors talked about how their girlfriends or wives would occasionally get annoyed at having to adhere to a schedule. Ethan and his wife would only have sex on Fridays, an arrangement that did not make her happy, so they tried having sex without climax. But then Ethan’s samples stopped passing. He talked to the donor manager, who told him, “You can’t have your cake and eat it, too. You have to abstain.”

Other than failing to abstain, donors reported a long list of reasons why their samples might not pass the bank’s strict requirements: being tired or stressed, getting sick, exercising right before donating, working outside in hot weather, drinking too much alcohol, eating poorly, smoking marijuana, and hot-tubbing. Charles, a twenty-nine-year-old graduate student who had donated sporadically for the last five years, noted, “if I haven’t been eating exactly as I should have or if I haven’t been getting enough sleep, I can tell my body isn’t ready to donate. After a while, you kind of get a feel for when you’re ready, and sometimes I just don’t feel up to it.”

If men had several failing samples in a row, bank staff sometimes inquired if anything had changed or offered pointers. Most donors found this advice helpful and altered their behavior, which included taking vitamins and other supplements, drinking more orange juice, eating more protein, or reducing alcohol consumption. Greg, a college student who donated twice a week, said he started drinking more beer over the summer and as a result was only passing 25% to 50% of his samples. He asked a donor friend as well as the donor manager and the bank’s physician how to improve his pass rate, and, in response to their advice, was

“changing a lot of my eating habits and a lot of my other habits so I can get more money [

laughs

].”

In sum, sperm donors certainly do not experience the deep anxiety of men producing samples for their wives’ fertility treatments. But their embodied experiences also do not conform to Laumann et al.’s description of masturbation as occurring in a “secluded personal realm” where “personal pleasure” is central.

19

Walking into a sperm bank requires that men overcome the stigma of masturbation, produce a semen sample in a small room, and then hand over the plastic cup to a lab technician, who will run tests to determine whether he will get credit for that deposit. Outside the bank, sperm donors must maintain bodily control, not only in terms of sexual activity, but also in terms of eating, drinking, and sleeping. So although men do derive some pleasure from the “sexual release,” it is just one small part of what is involved in being a paid sperm donor.

CONCLUSION

Women and men who are paid to produce sex cells must manage their own bodies: women through shots and surgery and men through routine masturbation and abstinence. Although they have very different physical experiences of gamete donation, both egg and sperm donors provide evidence that variation in social context is associated with variation in bodily experience. Egg donors describe the injections and egg retrieval in much less onerous terms than do infertile women, because being paid thousands of dollars and not trying to become pregnant results in a different embodied experience of IVF. Sperm donors portray masturbating for money as requiring a surprising amount of bodily discipline while rendering the orgasm less pleasurable, which leads them to make distinctions between their embodied experiences of masturbation inside and outside the sperm bank.

For some, these findings will make intuitive sense. After all, there is enormous heterogeneity in all kinds of bodily experiences. But there is a strong assumption, among both scholars and clinicians, that IVF is inherently difficult and demanding, an assumption that derives in part

from a well-developed feminist critique of the technology.

20

For example, anthropologist Monica Konrad interviewed British egg donors and was shocked to find that they described donation as “simple” and “quick.” Even after she read to them from a pamphlet describing the shots and surgery, she was “struck by [the donors’] reluctance to comment in any detail on certain aspects of the egg induction process. To an outsider, the process seemed an exceptional commitment, if not an onerous and risky undertaking.” In the end, Konrad steps in with her own assessment when she writes that the donors “

downplay

the considerable amount of preparation time that must be invested in the process” and are “

refusing

to acknowledge the pain, discomfort, and risk.”

21

Rather than dismissing egg donors’ statements, I suggest another explanation for why their descriptions do not conform to researchers’ expectations, namely that their embodied experiences of the technology

are

different from the infertile women who are most often the subject of research on IVF.

Social scientists have focused on the many ways in which people “see” the body or “think” about the body, but the experiences of gamete donors contribute to a growing literature that suggests there is also variation in how the body

feels

.

22

Some studies have begun to examine particular mechanisms through which the “social” manifests in the material body, with social factors including everything from individual experiences to structural inequalities. For example, stress results in physiological damage, major life events (such as divorce or the death of a spouse) increase the probability of illness, and relative class status may result in different levels of mortality.

23

In the medical market for sex cells, it is the social process of commodification that influences women’s and men’s embodied experiences of donation.

FOUR

Being a Paid Donor

Producing eggs and sperm involve very different physical processes, but the women and men who apply to be donors are very similar in one regard: most are drawn in by the prospect of being paid. In egg agencies, though, staffers draw on gendered cultural norms to talk about the money as compensation for giving a gift, yet sperm bank staffers consider payments to be wages for a job well done. Given that egg and sperm donors are walking in the door for similarly pecuniary reasons, what happens when they encounter the organizational framing of paid donation as a gift or a job?

By the organizational framing of paid donation, I mean the constellation of gendered practices and rhetorics in egg agencies and sperm banks that are detailed in

Chapter 2

, which include the amount of attention given to the donor/recipient relationship and the different payment

protocols. Women are paired with a specific recipient, and the donation involves a relatively brief but focused period of time in which the donor takes shots, attends medical appointments, and has her eggs retrieved. Thus, even when egg donors do not meet recipients, the idea that someone is on the other end of the exchange is more present, both because staffers talk about recipients more and because women know that their eggs are going to a specific person who has chosen them. In contrast, sperm donors do not hear much about recipients and are not allowed to meet them. Men are also donors for a much longer period of time during which they make routinized deposits at the bank, more like employees clocking in and out on a regular basis. The underlying message conveyed by these organizational practices, that donation is a gift or a job, is reinforced by payment policies: egg agencies disburse a lump sum at the end of the cycle regardless of how many eggs a woman produces, while sperm banks cut a check every two weeks—but only for those samples that meet bank standards.

There are countless sociological studies about how events or interactions are “framed” in different ways.

1

However, less is known about what happens when organizations rely on different kinds of frames for similar kinds of activities, particularly in terms of how such variation affects the individuals who are involved with those organizations. Kieran Healy has addressed this question in cross-national research on blood and organ donation. He found that donation programs “create and sustain their donor pools by providing opportunities to give and by producing and popularizing accounts of what giving means.”

2

Healy did not conduct qualitative research with donors though, so his finding raises new questions. Does “what giving means” change depending on the bodily good being donated, especially if those goods are more associated with male bodies or female bodies? Moreover, how do donors respond to an organization’s gift rhetoric when they are also receiving direct payments? These are pressing questions for scholars of bodily commodification, because there has been so much concern about the dehumanizing effects of being paid for parts of one’s body.

In this chapter, I look at how women and men who produce sex cells respond to the organizational framing of paid donation, finding that it

does

have consequences for how individuals experience bodily commodification. Despite the fact that egg and sperm donors are alike in being motivated by the compensation, and they spend the money on similar things, they end up adopting gendered conceptualizations of what it is they are being paid to do. Women speak with pride about the huge gift they have given, while men consider donation to be a job, and some sperm donors even reference feelings of alienation and objectification.

“I’M IN IT FOR THE MONEY”

The vast majority of egg and sperm donors I interviewed revealed that their initial interest in donation was sparked by the prospect of financial compensation, which is understandable given their life circumstances.

3

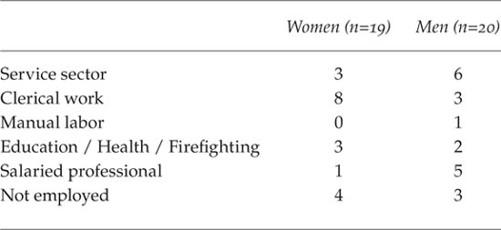

Most were working but were doing so in low-paying jobs that were often part-time (see

Table 2

). Moreover, about half the donors were also students, including those who were taking a few classes at the local junior college and those who were enrolled full-time at a four-year university. Of those who were not employed at the time of the interview, three women were students who worked in the service sector before donating eggs, one woman was a librarian who now takes care of her young children, and the three men were students whose primary financial support came from fellowships or family members.

Table 2

Egg and Sperm Donors’ Occupations

Given the low wages of service and clerical work as well as students’ perennial need for money, the prospect of earning thousands of dollars for providing sex cells exerts a strong pull. Megan, a twenty-two-year-old who went to school full-time while also holding down a full-time job as a clerk, said “I would fail out of school sometimes because I had to work so much.” After hearing Creative Beginnings’ advertisement on the radio, she emailed to ask for more information. She explained,

What came in the mail was just their poster. It said what they did, the opportunity to earn up to $5,000, so it would just seem like a lot of money to me. I’ve never had a lot of money all at once. It said anonymity guaranteed. It had photos of women who were young and my age and doing this type of thing. Sporty! [

laughs

] Then it has pictures of happy husbands and wives, brand new babies. It was really, really good marketing.

Later in the interview, she added that “it wasn’t a terrible amount of money. It wasn’t so much that it was irresistible. It was something that I chose to do, because it could help someone else.” Exhibiting a similar ambivalence about being too focused on the compensation, Gretchen, a recent college graduate, said “This is what makes me feel like a horrible person: I’m in it for the money. Honestly, my car is going to die. The boost in income is going to be nice.”

Men are not so reluctant to identify their primary interest in donation as monetary. Manuel, an undergraduate with a part-time library job when he began donating in his mid-twenties, explained, “As a student, I was thinking of which ways to make ends meet financially. That’s the bottom line. How can I make money without really getting a second job? Then you hear about things like sperm donation, so I looked it up on the Internet. My first step was just calling and finding out what kind of pay do you get? What do I need to do to make this happen? There was no desperation. I wasn’t hard up for money. This [library] job only pays so much, and the extra money could help.”

Dennis, a recent graduate of a prestigious university, did describe himself as somewhat desperate. He was living with roommates and working at several part-time jobs when he finally decided to respond to a Western Sperm Bank ad he had seen many times before.