Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm (28 page)

Read Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm Online

Authors: Rene Almeling

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Medical, #Economics, #Reproductive Medicine & Technology, #Marriage & Family, #General, #Business & Economics

APPENDIX B

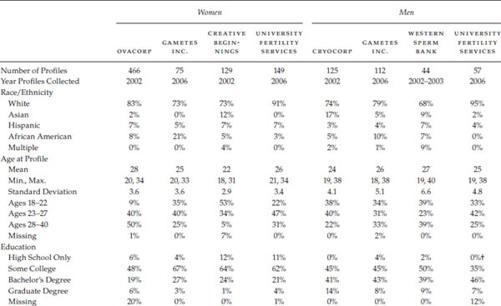

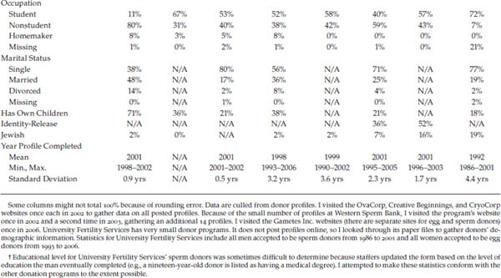

Demographics of Donors Based on Profiles at Egg and Sperm Donation Programs

Notes

INTRODUCTION

1

. Debora Spar of the Harvard Business School (2006, 3) estimated revenues for each of the following components of the fertility industry in 2004: fertility drugs at $1,331,860,000; IVF at $1,038,528,000; diagnostic tests at $374,900,000; donor sperm at $74,380,000; donor eggs at $37,773,000; and surrogate mothers at $27,400,000 for a total of $2,884,841,000.

2

. National statistics for sperm donation have not been generated since 1987, when the United States Office of Technology Assessment (1988) estimated that 30,000 children born that year had been conceived with donated sperm. For a discussion of the number of egg donation cycles per year, see Chapter 1.

3

. One recent study reported an average payment of $4,200 per egg donation (Covington and Gibbons 2007).

4

. On prostitution, see Bernstein (2007). On the medical profession’s use of bodies and body parts to study anatomy, see Richardson (1987). Selling blood is not illegal, but most whole blood donors in the United States are not paid. Individuals do sell a part of blood called plasma (Espeland 1984), and sometimes people with rare blood types are paid to provide blood. The National Organ Transplant Act makes it illegal to sell one’s organs in the United States. However, for both blood and organs, there is a highly developed secondary market through which such goods are exchanged among medical professionals (Healy 2006, Timmermans 2006). On face transplants, see Talley (2008).

5

. Over time, the inability to become pregnant has become defined as a “medical problem” through a process called medicalization, in which the medical profession gains authority to define conditions as requiring medical intervention (Conrad 2007). On the history of infertility, see Pfeffer (1993) and Becker (2000).

6

. Women and men are equally likely to experience infertility, but incidence rates are based on women’s responses to the National Survey of Family Growth. See Stephen and Chandra (2006), which reports an infertility rate of 7.4% among married women in 2002 and includes a discussion of social trends, including delayed marriage, delayed childbearing, and increasing educational attainment.

7

. Mamo (2007).

8

. On the history of insemination, see Sherman (1964), Daniels (2006), and Moore (2007). Sperm that is placed directly into a woman’s uterus must be “washed” of all seminal fluid to prevent the uterus from expelling it. Sperm donation programs do this at the time of the donation, and they sell “washed” samples for slightly higher prices than regular samples.

9

. In the 1930s, researchers John Rock and Miriam Menkin began to purposely schedule ovary removal surgeries when the patient would be ovulating. For six years, Menkin took each ovary back to the lab and looked for ripe eggs to mix with sperm. In 1944, they reported the first successful fertilization of sperm and egg in the lab (Duka and DeCherney 1994, 83). On the history of IVF, see Duka and DeCherney (1994) and Thompson (2005).

10

. An increasing awareness of the problems associated with gestating multiple fetuses have led to calls for physicians to reduce the number of embryos transferred to the uterus (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006). Yet, American physicians retain wide latitude in how they practice, as is evident in the case of Nadya Suleman. In 2008, her physician transferred far more embryos than was standard practice, and she gave birth to eight children, which led to a media firestorm during which she was dubbed “Octomom” in headline after headline.

11

. On surrogacy, see Ragoné (1994), Markens (2007), and Teman (2010). When surrogacy was first offered through commercial agencies in the early 1980s, the surrogate mother (the woman gestating the fetus) also provided the egg. This was the situation in the controversial “Baby M” case in 1987, in which Mary Beth Whitehead provided the egg and gestational services for William and Mary Stern before reneging on the contract and seeking custody of the child. With the development of egg donation, it is now the case that most surrogate mothers are not genetically related to the fetuses they gestate (Ragoné 1998).

12

. Practice Committee of ASRM (2008b). Empirical studies have been conducted by Sauer (2001) and Maxwell, Cholst, and Rosenwaks (2008). According to ASRM, ovarian hyperstimulation occurs when “the ovaries become swollen and painful. Fluid may accumulate in the abdominal cavity and chest, and the patient may feel bloated, nauseated, and experience vomiting or lack of appetite.” ASRM estimates that about a third of all women who take fertility medications will experience mild hyperstimulation, which is treated with over-the-counter painkillers and a reduction in activity. It estimates that around 1% will experience severe hyperstimulation, which can require hospitalization.

13

. Schneider (2008) and Elton (2009).

14

. See Haimes (1993) for a discussion of how gendered understandings of gamete donation shaped the initial regulatory deliberations in Britain.

15

. In 1984, ASRM created an ethics committee to investigate the ramifications of IVF. Committee members included physicians, lawyers, ethicists, biologists, and a priest. The first ethics report was issued in 1986, and follow-up reports have been generated every few years (Duka and Decherney 1994, 188).

16

. See, for example, Landes and Posner (1978) on adoption markets and Becker and Elias (2007) on organ markets.

17

. Titmuss (1971, 158).

18

. Murray (1996, 62).

19

. Nussbaum (1998, 695).

20

. Titmuss (1971, 245–6).

21

. Zelizer (1979), Zelizer (1985), and Zelizer (2005).

22

. Zelizer (1988, 618). As Zelizer’s theoretical project is most developed in the commodification of intimate relationships, such as those between husband and wife or parent and child, this analysis of the medical market for sex cells builds on her work by examining the intimate processes of bodily commodification among those who did not previously know each other. My research also differs from Zelizer’s in its focus on particular bodily goods as opposed to the commodification of whole persons.

23

. Radin (1996, xiii).

24

. Healy (2006, 120). Emphasis in original. Healy’s research is part of a trend in economic sociology toward empirical studies of markets (e.g., Baker [1984], Abolafia [1996], and Velthuis [2005]), but it is one of the few empirical studies of markets for bodily goods.

25

. See De Beauvoir (1989), Ortner (1974), and Rubin (1975).

26

. Yanagisako and Collier (1990, 132).

27

. Butler (1993). See also Fausto-Sterling (2000).

28

. Martin (1991, 500).

29

. For a review, see England and Folbre (2005).

30

. Nelson and England (2002, 1). On /files/02/13/03/f021303/public/private as a fractal distinction, see Gal and Kligman (2000). On gendered norms of parenthood, see Chodorow (1978), Connell (1987), Hays (1996), Coltrane (1996), Blair-Loy (2003), and Kimmel (2006).

31

. Appadurai (1986, 11–12). See Marx (1936) and Mauss (1967). On the distinction between commodities and gifts, see Rubin (1975), Gregory (1982), and Carrier (1995).

32

. Sharp (2000, 292).

33

. Radin differentiates “market rhetoric” from actual buying and selling and discusses the power of such rhetoric (1996, 104).

34

. Scheper-Hughes (2001b, 2). Emphasis added.

35

. Hochschild (1983). See, for example, Kanter (1977), Acker (1990), Pierce (1995), Williams (1995), Hondagneu-Sotelo (2001), Sherman (2007), and Otis (2008).

36

. Lopez (2006, 137).

37

. The bioethical literature often provides examples of individual experiences, commonly drawn from newspaper reports, but this does not constitute systematic research on the experience of commodification. Radin (1996) points to the possibility of variation in how payment is experienced, but she did not collect empirical data. Waldby and Mitchell (2006) did not collect data from donors. Titmuss (1971) and Healy (2006) did analyze data from blood and/or organ donors but in the form of surveys and not qualitative interviews and observation. Bernstein (2007) includes an analysis of the embodied experience of commodification, but it is a study of sex workers.

38

. See, for example, Jordan (1983), Gordon (1976), Luker (1984), Katz Rothman (1986), Ragoné (1994), Ginsburg and Rapp (1995), Browner and Press (1995), Franklin (1997), Roberts (1997), Kligman (1998), Beisel and Kay (2004), Markens (2007), and Teman (2010).

39

. Sharp (2000).

40

. This sample of six donation programs is limited in three ways. First, it is not a random sample of all donation programs in the United States, a selection strategy that, although ideal, would be difficult to enact because there is no comprehensive list of all such programs. Second, this sample does not capture data about “private” donation, which takes place within family and friendship networks or through contacts made on the Internet. Systematic recruitment of these subjects would be difficult, but more importantly for the theoretical project of analyzing variation in commodification, donors to family and friends are rarely paid, and the influence of personal relationships would be difficult to analyze separately from the experience of providing genetic material. In terms of Internet donation, few men participate, which makes a gendered comparison difficult. Thus, I limited my project to analyzing variation in bodily commodification within the formalized structure of organized donation programs. Third, in focusing on the staff and donors at organized donation programs, I did not collect data about recipients, who, as consumers of reproductive technologies, create demand for eggs and sperm. Instead, I draw on existing research about how recipients make decisions about donors and how those decisions are influenced by staff at organized donation programs (e.g. Becker 2000; Becker, Butler, and Nachtigall 2005).