She Walks in Shadows (19 page)

Read She Walks in Shadows Online

Authors: Silvia Moreno-Garcia,Paula R. Stiles

“Unlock it,” I told him and pushed him, stumbling, ahead of me. I quickly turned and locked the door behind us, uncertain of who might otherwise come into the room. We had passed through several secured doors to reach this lab. Between Doctor Beatty’s identification and my own powers of persuasion, it was not terribly difficult. Nonetheless, I had been increasingly nervous as we walked along, forcing him to stop frequently to exchange lingering looks with me in the hall, as if we were young lovers.

By the time we reached the laboratory, my victim was flagging badly, his face gone from the rosy flush of pleasant arousal to a dark red flush of hypnotic ecstasy. His hands trembled and a light sweat had broken out over his face. He would go into shock soon, perhaps even die.

It took him nearly a full minute to fumble the key into the padlock and release the chain. By the time he was finished, I had begun to feel pity for him.

I walked up beside him, feeling an impulse of kindness. “Give me your handkerchief.”

He pulled the cotton square from his jacket pocket and gave it to me. I turned him toward me like a child, and gently dabbed his brow and cheeks. “I want you to sit down now, Louis.” I put a gloved hand to his cheek and sharpened my voice to issue a command. “You will sit down, close your eyes, and breathe deeply. Do you understand?”

He had already closed his eyes, turning his head to receive my caress like an affectionate pet. “Yes, Miss. I understand.”

I accompanied him to the desk in the corner of the room and settled him into the chair. He allowed me to fold his arms on the desk and lay his head across them like a tired schoolboy who has finished his exam. “So beautiful,” he murmured to himself quietly. “So beautiful.”

I turned away from him. The steel lid of the dissection table shone under the lights. Even from here, I could smell the funeral spices of her body: cassia and cinnamon, natron and myrrh.

I crossed the room and reached for both the handles, blinking back tears, and opened the double lid.

She lay on her left side, chin to her chest, knees bent in a fetal crouch. Her body had been desecrated, of course, for the sake of “Science.” The linen bandages were already cut away from her withered face, her right arm, and her right foot. In a specimen box, they had gathered her jewelry, and the amulets incorporated into her wrappings, to ward her in the Lands of the Dead.

Her arms were longer, her legs shorter, than those of a Human. Her hand was delicate, the thumb nearly the same length as the fingers. The robust bones of her face were beautiful and fierce: her powerful jaw, her withered lips pulled back over perfect ivory tusks. Her mane was well-preserved, still golden-blonde over her head, shoulders and neck. Normally, her eyes would have been closed with beeswax, but her Human consort had replaced the long-withered flesh orbs with two polished spheres of blue topaz.

I put my suitcase on the empty table beside her and opened it.

“Wait,” the old man said softly. He had risen from his bent position, but could not yet summon the will to rise to his feet. “What are you doing, Miss?”

“I am taking her.” I moved briskly, removing a white sheet from the case. I draped it over the mummy and quickly tucked her into the sheet. My strength was more than equal to the task: Centuries after her mummification, her remaining flesh and bones were light and crisp as autumn leaves. I winced as the old wrappings crumbled and flaked away at my touch ... but there was no time for delicacy.

“You ... you’re taking the Ape Princess?”

I whirled to face him. All of the anxiety I had been holding within me suddenly seemed to burst into rage and grief.

“She is not an APE!” I shrieked the words at him. He cringed away from me, whimpering submission, but I had lost control. I crossed the room again in a single inhuman bound, landing on the desk before him in a half-crouch.

“How DARE you call her an APE!” I lashed out with a fist, smashing a deep dent into the heavy metal file cabinet beside him. He urinated helplessly in the face of my fury, rank yellow liquid trickling into his shoes and pattering onto the lab floor.

The old man was making little feeble warding gestures of supplication. I caught his wrists in an angry grip and roared wordlessly into his face, the belling cry of a queen’s dominance.

“How DARE you touch her!?” I let him go and my fist thudded into the file cabinet again, driving the dent deeper. “How DARE you violate her tomb!?”

“It wasn’t me!” he wailed. His crossed his arms over his face protectively. “They only asked me to examine her! Please!” He burst into sobs. “I never meant any harm!”

A male of my own species would have responded with his own aggression, forcing me to prove my worthiness by crushing him. The swift capitulation of a Human male was like a sedative drug — it quenched my rage instantly, leaving me hollow. Grief filled my chest like rainwater in a blackened crater.

I retreated slowly from the desk, stepping backward onto the floor, resuming my bipedal stance.

“No,” I admitted. “It wasn’t you. Not you, personally.” I turned away from him. “It is the way of your people. You are all grave robbers and thieves. This place is a testament to that, if nothing else.”

I bent and gathered up the body of my ancestress, folding her with reverence into the suitcase, and emptied the box of her ornaments onto her shroud — heavy rings, chains and bracelets of electrum, all marked with the hieroglyphic script of Leng.

“Your mistake was to stray outside your own species, Doctor Beatty. Violate the tombs of your own people, rob each other blind, steal each other’s corpses and make puppets for all I care! But a woman of my race is no Truganini.”

As I locked the case closed, he spoke again. “She isn’t Human.”

I turned again. He had collected himself, although the storm of terror had left him red and puffy. “I don’t know why you’re stealing her,” he said hoarsely. “But you speak as if you’re related to her, somehow.” He swallowed, his eyes owlishly wide beneath his spectacles. “That isn’t possible, Miss.”

I pulled my lips back over my teeth. “She is my thrice-great grandmother. My people live longer lives than yours, Louis Beatty.”

“She isn’t Human.” He spoke more firmly now. In this, if nothing else, he was confident. “Her limbs, her skull, her hands ... she’s a hominid, yes, not

Homo sapiens

.”

“No,” I agreed. “Our species split apart over three hundred thousand years ago, at the dawn of a great Cold Age. We are still close enough cousins to interbreed, but the results ... are unpredictable.”

He pushed the glasses further up his nose with a palsied hand. “Was she really ... a surviving

Homo erectus

? In 1755?”

I huffed soft laughter at him, pursing my lips. “Has your own species not changed in the last 300,000 years? You can call us

Homo jermynus

, if you like. We do not care. Perhaps the name would comfort poor Arthur, in the Lands of the Dead. Things are always hard for mixed children.”

He stubbornly insisted, even though he was still shaking like a leaf. “You cannot be related to her, Miss.”

I moved toward him. “You think not? Why is that, Doctor Beatty?” I pulled the lips back over my teeth in a dangerous, aggressive leer. “Because you see a beautiful woman when you look at me?”

He looked up as I loomed over him. “Yes. You are the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen.”

“Your mind lies so that you can see the truth.” I laughed at him again. “Yes, I am beautiful, Louis Beatty. The women of a superior race are always ‘beautiful.’ You want to mate with me and make strong children. Offspring who will inherit my superior genes and survive the winds of the Great Plateau.”

His brow creased in confusion. “I don’t understand.”

“You will.” I caressed his face with a gloved hand. “My people walk the Wastes that span the world, Louis Beatty. Our ancient gates let us venture forth into many lands; the Congo was only one. Wherever we step forth into the world of Man, we are worshipped as gods and take mates as we please. Our children pass on the traits for golden hair, for blue eyes, or stronger bones. Wherever you see those features, you are seeing our descendants among you.”

I bent and kissed his tiny mouth in parting, then removed one glove to reveal the pale ivory flesh and golden fur beneath. I looked directly into his eyes and spoke a final command.

“You no longer have my permission to see what you wish to see, Louis Beatty. I command you to see me as I am.”

He gave a strangled scream at the sight of my true face, eyes wide in shock, and threw himself away from me with such violence that both he and his chair toppled over onto the hard stone floor.

I left him lying on his side, clutching his chest, as I patiently pulled the gray leather glove back over my strange hand, re-arranged the shawl to cover my mane, and picked up my suitcase.

“Rest easy, Great Mother,” I told her, speaking the language of the Plateau. “I am taking you home.”

CHOSEN

Lyndsey Holder

“

KEZIAH,” I WHISPERED

and my body vibrated with the thrill of saying her name in the space where she once lived, in the grounds that were still permeated with the thick miasma of her power.

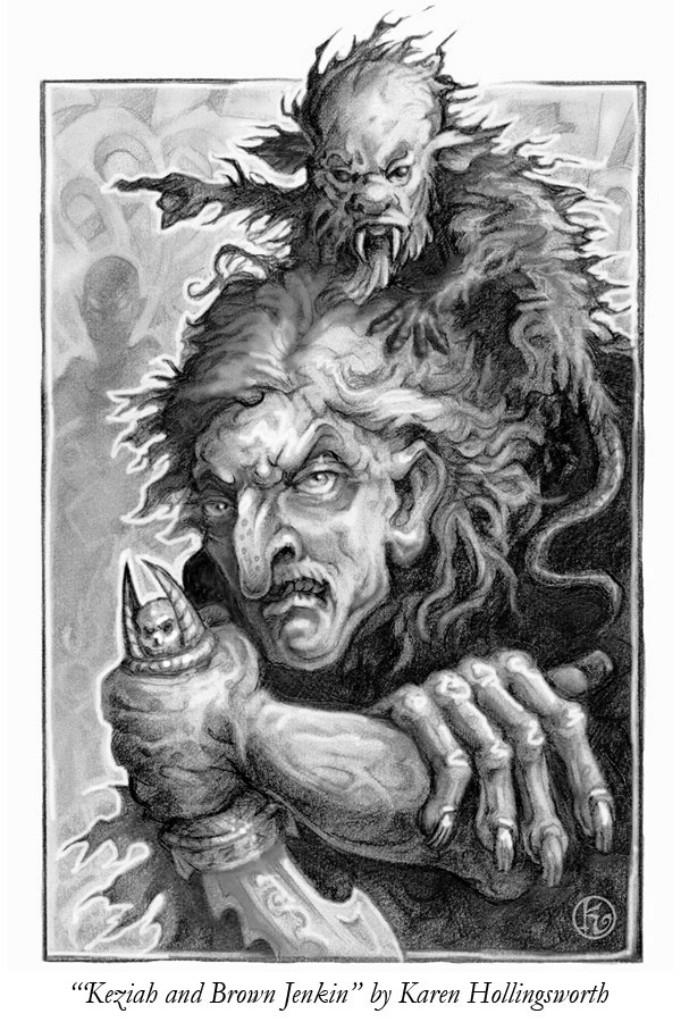

I’d dreamed of her since I was small, though “dream” seems too insignificant a word to describe what we shared. She visited me at least one night a month, she and her strange familiar, always when I was asleep, but our time together wasn’t disjointed and vague like the dreams I was used to having. I was scared of her, at first — what child wouldn’t be? A haggard crone, and a rat with a monstrous face and menacing teeth, should have no place in the dreams of the innocent, yet here they were in mine.

I was afraid at first, but my fear dissipated quickly and I began to look forward to our visits with excitement. She told me all sorts of stories about gods and dark things and creatures that sounded more terrifying than any monsters I’d read about. I’d never heard of those creatures, or the places they came from, but I believed in them with all my heart.

Ancient, important-looking books covered every available surface of the room we met in and a ghostly, violet light whose source I was never able to determine cast an unearthly glow throughout the space. Everything looked wrong and weird in that light — I wondered, sometimes, if the books scattered around were innocuously pedestrian, and it was only the ethereal glow that made them seem as though they contained instructions for dark rituals. I could easily have looked over at one of the many that lay open and read from it, but doing so seemed as though it would be a horrible breach of etiquette for some reason I couldn’t quite explain. I was terrified of upsetting Keziah -- initially, because she was such a frightening figure, but later, because I worried that angering her might cause her to stop visiting me.

At first, I was distracted by the strange geometry of the space. I lived with my parents in a rectangular room inside a rectangular apartment inside a rectangular building full of rectangles. I had never seen the kinds of angles and curves and half-walls that outlined the space in which Keziah lived. I made up my mind that I would have a room like hers one day.

It must have made for a bizarre picture: a gnarled old woman in a shapeless brown robe with wispy grey hair; a rat-bodied creature with a distorted face, grizzled beard, and murderously sharp teeth perched on her shoulder; and a dark-haired and bright eyed girl in cheerful, pink pyjamas.

Often, I wondered if she was lonely. Was she spending time with me because she didn’t have family, because she didn’t have her own daughter to teach these things to? I think I always knew that she was dead, though at that age, I didn’t really understand what death meant. I understand it even less now that I’m older.

I drew pictures of her and Brown Jenkin in school, as well as some of the creatures from her stories: the Black Man, Shub-Niggurath, Azathoth. What began as concerned looks grew to worried questions and culminated in a visit to a child psychiatrist. I was, he decided, a lonely child who wanted to feel special, so I had created a world for myself where I was the Chosen One. My parents needed to spend more time with me, he concluded. If they could make me feel important, I wouldn’t need to make up stories.

I mulled over what my parents told me of his assessment in the car ride home. At first, I was angry. If I were going to dream up a fairy godmother, I’d have made her plump and soft, and smelling of cookie dough and brown sugar and full of love and laughter. She’d tell me stories about knights and princesses and happy things. If there were an animal following her around, it would be an energetic puppy.

I hadn’t thought of myself as a “chosen one” before he’d said so, but I realized afterwards that it was true. Every child reads stories about how one day, a normal boy or girl finds out that they are different than every other child in the world in the best way possible and every child waits for the day when they, too, find their golden ticket. Most of them are disappointed. Not me. Keziah’s presence in my life proved how very important I was. I had a big, amazing story ahead of me.