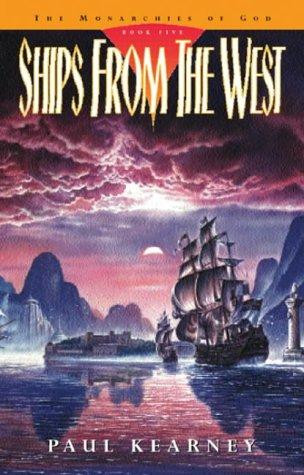

Ships from the West

Read Ships from the West Online

Authors: Paul Kearney

( Monarchies of God - 5 )

Paul Kearney

Ships From The West

PAUL KEARNEY

For Peter Talbot

Prologue

Year of the Saint 561

Richard Hawkwood hauled himself out of the gutter whence the crowds had deposited him, and viciously shoved his way through the cheering throng, stamping on feet, elbowing right and left and glaring wildly at all who met his eye. Cattle. God-damned cattle.

He found a backwater of sorts, an eddy of calm in the lee of a tall house, and there paused to catch his breath. The cheering was deafening, and en masse the humble folk of Abrusio were none too fragrant. He wiped sweat from his eyelids. The crowd erupted into a roar and now from the cobbled roadway there came the clatter of hooves. A blast of trumpets and the cadence of booted feet marching in time. Hawkwood ran his fingers through his beard. God’s blood, but he needed a drink.

Some enthusiastic fools were throwing rose petals from upper windows. Hawkwood could just glimpse the open barouche through the crowds, the glint of silver on the grey head within, and beside it a brief blaze of glorious russet hair shot through with amber beads. That was it. The soldiers tramped on in the raucous heat, the barouche trundled away, and the crowd’s frenzy winked out like a pinched candle flame.The broad street seemed to unclench itself as men and women dispersed, and the usual street cries of Abrusio’s Lower City began again. Hawkwood felt for his purse - still there, although as withered as an old woman’s dugs. A lonely pair of coins twisted and clinked under his fingers. Enough for a bottle of the Narboskim at any rate. He was due at the Helmsman soon. They knew him there. He wiped his mouth and set off, a spare, haggard figure in a longshoreman’s jerkin and sailor’s breeks, his face nut-brown above the grizzled beard. He was forty-eight years old.

‘Seventeen years,’ Milo, the innkeeper, said. ‘Who’d have thought he’d last so long? God bless him, I say.’

A rumble of slurred but cheerful assent from the men gathered about the Helmsman’s tables. Hawkwood sipped his brandy in silence. Was it really that long? The years winked past so quickly now, and yet this time he had on his hands here, in places like this - the present - it seemed to stretch out unendingly. Bleary voices, dust dancing in the sunlight. The glare of the day fettered in the burning heart of a wineglass.

Abeleyn IV, son of Bleyn, King of Hebrion by the Grace of God. Where had Hawkwood been the day the boy-king was crowned? Ah, of course. At sea. Those had been the years of the Macassar Run, when he and Julius Albak and Billerand and Haukal had made a tidy sum in the Malacars. He remembered sailing into Rovenan of the Corsairs as bold as brass, all the guns run out and the slow-match smoking about the deck. The tense haggling, giving way to a roaring good fellowship when the Corsairs had finally agreed upon their percentage. Honourable men, in their own way.

That, Hawkwood told himself, had been living, the only true life for a man. The heave and creak of a living ship under one’s feet - answerable to no one, with the whole wide world to roam.

Except that he no longer had that hankering to roam. The life of a mariner had lost much of its shine in the past decade, something he found hard to admit, even to himself, but which he knew to be true. Like an amputated limb which had finally ceased its phantom itching.

Which reminded him why he was here. He swallowed back the foul brandy and poured himself some more, wincing. Narboskim gut-rot. The first thing he would do after - after today would be to buy a bottle of Fimbrian.

What to do with the money? It could be a tidy sum. Maybe he’d ask Galliardo about investing it. Or maybe he’d just buy himself a brisk, well-found cutter, and take off to the Levangore. Or join the damned Corsairs, why not.

He knew he would do none of these things. It was a bitter gift of middle age, self-knowledge. It withered away the damn fool dreams and ambitions of youth leaving so-called wisdom in its wake. To a soul tired of making mistakes it sometimes seemed to close every door and shutter every window in the mind’s eye. Hawkwood gazed into his glass, and smiled. I am become a sodden philosopher, he thought, the brandy loosening up his brain at last.

‘Hawkwood? It is Captain Hawkwood, is it not?’ A plump, sweaty hand thrust itself into Hawkwood’s vision. He shook it automatically, grimacing at the slimy perspiration which sucked at his palm.

‘That’s me. You, I take it, are Grobus.’

A fat man sat down opposite him. He reeked of perfume, and gold rings dragged down his earlobes. A yard behind him stood another, this one broad-shouldered and thuggish, watchful.

‘You’ve no need of a bodyguard here, Grobus. No one who asks for me has any trouble.’

‘One cannot be too careful.’ The fat man clicked his fingers at the frowning innkeeper. ‘A bottle of Candelarian, my man, and two glasses - clean ones, mind.’ He dabbed his temples with a lace handkerchief.

‘Well, Captain, I believe we may come to an arrangement. I have spoken to my partner and we have hit upon a suitable sum.’ A coil of paper was produced from Grobus’s sleeve. ‘I trust you will find it satisfactory.’

Hawkwood looked at the number written thereon, and his face did not change.

‘You’re in jest, of course.’

‘Oh no, I assure you. This is a fair price. After all—’ ‘It might be a fair price for a worm-eaten rowboat, not for a high-seas carrack.’

‘If you will allow me, Captain, I must point out that the

Osprey

has been nowhere near the high seas for some eight years now. Her entire hull is bored through and through with teredo, and most of her masts and yards are long since gone. We are talking of a harbour hulk here, a mere shell of a ship.’

‘What do you intend to do with her?’ Hawkwood asked, staring into his glass again. He sounded tired. The coil of paper he left untouched on the table between them.

‘There is nothing for it but the breaker’s yard. Her interior timbers are still whole, her ribs, knees and suchlike sound as a bell. But she is not worth refitting. The navy yard has already expressed an interest.’

Hawkwood raised his head, but his eyes were blank and sightless. The innkeeper arrived with the Candelarian, popped the cork and poured two goblets of the fine wine. The Wine of Ships, as it was known. Grobus sipped at his, watching Hawkwood with a mixture of wariness and puzzlement.

‘That ship has sailed beyond the knowledge of geographers’, Hawkwood said at last. ‘She has dropped anchor in lands hitherto unknown to man. I will not have her broken up.’

Grobus pinched wine from his upper lip. ‘If you will forgive me, Captain, you do not have any choice. A multitude of heroic myths may surround the

Osprey

and yourself, but myth does not plump out a flaccid purse - or fill a wine glass for that matter. You already owe a fortune in harbour fees. Even Galliardo di Ponera cannot help you with them any more. If you accept my offer you will clear your debts and have a little left over for your - for your retirement. It is a fair offer I am making, and—’

‘Your offer is refused’, Hawkwood said abruptly, rising. ‘I am sorry to have wasted your time, Grobus. As of this moment, the

Osprey

is no longer for sale.’

‘Captain, you must see sense—’

But Hawkwood was already striding out of the inn, the bottle of Candelarian swinging from one hand.

A multitude of heroic myths.

Is that what they were? For Hawkwood they were the stuff of shrieking nightmare, images which the passing of ten years had hardly dulled.

A slug from the neck of the bottle. He closed his eyes gratefully for the warmth of it. My, how the world had changed - some things, anyway.

His

Osprey

was moored fore and aft to anchored buoys in the Outer Roads. It was a fair pull in a skiff, but at least here he was alone, and the motion of the swell was like a lullaby. Those familiar stinks of tar and salt and wood and seawater. But his ship was a mastless hulk, her yards sold off one by one and year by year to pay for her mooring rent. A stake in a freighting venture some five years before had swallowed up what savings Hawkwood had possessed, and Murad had done the rest.

He thought of the times on that terrible journey in the west when he had stood guard over Murad in the night. How easy murder would have been back then. But now the scarred nobleman moved in a different world, one of the great of the land, and Hawkwood was nothing but dust at his feet.

Seagulls scrabbling on the deck above his head. They had covered it with guano too hard and deep to be cleared away. Hawkwood looked out of the wide windows of the stern cabin within which he sat - these at least he had not sold -and stared landwards at Abrusio rising up out of the sea, shrouded in her own smog, garlanded with the masts of ships, crowned by fortresses and palaces. He raised the bottle to her, the old whore, and drank some more, setting his feet on the heavy fixed table and clinking aside the rusted, broad-bladed hangar thereon. He kept it here for the rats— they grew fractious and impertinent sometimes - and also for the odd ship-stripper who might have the stamina to scull out this far. Not that there was much left to strip.

That scrabbling again on the deck above. Hawkwood glared at it irritably but another swallow of the good wine eased his nerves. The sun was going down, turning the swell into a saffron blaze. He watched the slow progress of a merchant caravel, square-rigged, as it sailed close-hauled into the Inner Roads with the breeze - what there was of it - hard on the starboard bow. They’d be half the night putting into port at that rate. Why hadn’t the fool sent up his lateen yards?

Steps on the companionway. Hawkwood started, set down the bottle, reached clumsily for the sword, but by then the cabin door was already open, and a cloaked figure in a broad-brimmed hat was stepping over the storm sill.

‘Hello, Captain.’

‘Who in the hell are you?’

‘We met a few times, years ago now.’ The hat was doffed, revealing an entirely bald head, two dark, humane eyes set in an ivory-pale face. ‘And you came to my tower once, to help a mutual friend.’

Hawkwood sank back in his chair. ‘Golophin, of course. I know you now. The years have been kind. You look younger than when I last saw you.’

One beetling eyebrow raised fractionally. ‘Indeed. Ah, Candelarian. May I?’

‘If you don’t mind sharing the neck of a bottle with a commoner.’

Golophin took a practised swig. ‘Excellent. I am glad to see your circumstances are not reduced in every respect, Captain.’

‘You sailed out here? I heard no boat hook on.’

‘I got here under my own power, you might say.’

‘Well, there’s a stool by the bulkhead behind you. You’ll get a crick in your neck if you stoop like that much longer.’

‘My thanks. The bowels of ships were never built with gangling wretches like myself in mind.’

They sat passing the bottle back and forth companionably enough, staring out at the death of the day and the caravel’s slow progress towards the Inner Roads. Abrusio came to twinkling life before them, until at last it was a looming shadow lit by half a million yellow lights, and the stars were shamed into insignificance.

The lees of the wine at last. Hawkwood kissed the side of the bottle and tossed it in a corner to clink with its empty fellows. Golophin had lit a pale clay pipe and was puffing it with evident enjoyment. Finally he thumbed down the bowl and broke the silence.

‘You seem a remarkably incurious man, Captain, if I may say so.’

Hawkwood stared out the stern windows as before. ‘Curiosity as a quality is overrated.’

‘I agree, though it can lead to the uncovering of useful knowledge, on occasion. You are bankrupt I hear, or within a stone’s cast of it.’

‘Port gossip travels far.’

‘This ship is something of a maritime curiosity.’ ‘As am I.’

‘Yes. I had no idea of the hatred Lord Murad bears for you, though you may not believe that. He has been busy, these last few years.’

Hawkwood turned. He was a black silhouette against the brighter water shifting behind him, and the last red rays of the sun had touched the waves with blood.

‘Remarkably busy.’

‘You should not have refused the reward the King offered. Had you taken it, Murad’s malignance would have been hampered at least. But instead he has had free rein these last ten years to make sure that your every venture fails. If one must have powerful enemies, Captain, one should not spurn powerful friends.’

‘Golophin, you did not come here to offer me half-baked truisms or old wives’ wisdom. What do you want?’

The wizard laughed and studied the blackened leaf in his pipe. ‘Fair enough. I want you to enter the King’s service.’

Taken aback, Hawkwood asked, ‘Why?’

‘Because kings need friends too, and you are too valuable a man to let crawl into the neck of a bottle.’

‘How very altruistic of you’, Hawkwood snarled, but his anger seemed somehow hollow.

‘Not at all. Hebrion, whether you choose to admit it or no, is in your debt, as is the King. And you helped a friend of mine at one time, which sets me in your debt also.’

‘The world would be a better place if I had not bothered.’

‘Perhaps.’ There was a pause. Then Hawkwood said quietly, ‘He was my friend too.’

The light had gone, and now the cabin was in darkness save for a slight phosphorescence from the water beyond the stern windows.

‘I am not the man I was, Golophin’, Hawkwood whispered. ‘I am become afraid of the sea.’

‘We are none of us what we were, but you are still the master mariner who brought his ship back from the greatest voyage in recorded history. It is not the sea you fear, Richard, but the things you found dwelling on the other side of it. Those things are here, now. You are one of a select few who have encountered them and lived. Hebrion has need of you.’