Shrinks (39 page)

Authors: Jeffrey A. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology / Mental Health, #Psychology / History, #Medical / Neuroscience

Today, psychiatrists are trained to evaluate their patients using the latest techniques of neuroscience

and

the most cogent psychodynamic principles of mental function. They use brain-imaging technology

and

carefully listen to patients’ accounts of their experiences, emotions, and desires. Ken Kendler, professor of psychiatry and human genetics at Virginia Commonwealth University and one of the most cited psychiatric researchers alive, has characterized this unified, open-minded approach to mental illness as “pluralistic psychiatry.”

In an insightful 2014 paper, Kendler cautions the newly dominant psychiatric neuroscientists against the “fervent monism” that characterized the psychoanalysts of the 1940s and ’50s and the social psychiatrists of the 1960s and ’70s, who saw mental illness through a narrow theoretical lens and proclaimed their approach the only valid one. Their exclusionary approach to psychiatry reflects what Kendler calls “epistemic hubris.” The best antidote for this hubris, observes Kendler, is an evidence-based pluralism.

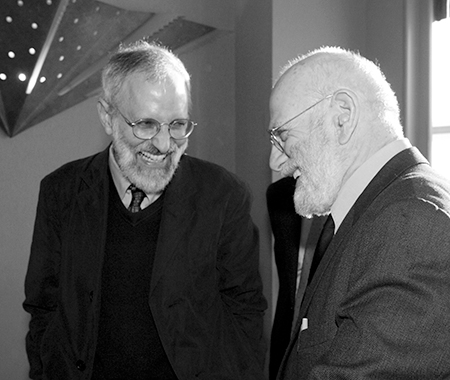

Ken Kendler (left) and Oliver Sacks at a reception in New York City in 2008. (Courtesy of Eve Vagg, New York State Psychiatric Institute)

Eric Kandel is justly famous for his role in launching the brain revolution in psychiatry; the full sweep of his career reflects a pluralistic vision of mental illness. While Kandel’s research focused on unraveling the neurobiology of memory, it was motivated and framed by his belief in the psychodynamic theories of Freud. He never relinquished his guiding faith that even if some of Freud’s specific ideas were wrong, the psychodynamic perspective on the mind was as necessary and valuable as the biological perspective. Kandel’s pluralism was reflected in a seminal paper he published in 1979 in the

New England Journal of Medicine

entitled “Psychotherapy and the Single Synapse.” In the paper, Kandel observed that psychiatrists tended to fall into two types—the “hard-nosed” psychiatrists who yearned for biological explanations of disorders, and the “soft-nosed” psychiatrists who believed that biology had delivered little of practical use and that the future of psychiatry lay in the development of new psychotherapies. Then Kandel observed that this apparent tension in perspectives could actually be a source of future progress, as the two sides were forced to contend and eventually reconcile with each other. Kandel still maintains his pluralistic perspective today, as seen in his 2013

New York Times

op-ed, written in response to David Brooks’s critique of the

DSM-5

:

This new science of the mind is based on the principle that our mind and our brain are inseparable. The brain is responsible not only for relatively simple motor behaviors like running and eating, but also for complex acts that we consider quintessentially human, like thinking, speaking, and creating works of art. Looked at from this perspective, our mind is a set of operations carried out by our brain. The same principle of unity applies to mental disorders.

So after all is said and done, what

is

mental illness? We know that mental disorders exhibit consistent clusters of symptoms. We know that many disorders feature distinctive neural signatures in the brain. We know that many disorders express distinctive patterns of brain activity. We have gained some insight into the genetic underpinnings of mental disorders. We can treat persons with mental disorders using medications and somatic therapies that act uniquely on their symptoms but exert no effects in healthy people. We know that specific types of psychotherapy lead to clear improvements in patients suffering from specific types of disorders. And we know that, left untreated, these disorders cause anguish, misery, disability, violence, even death. Thus, mental disorders are abnormal, enduring, harmful, treatable, feature a biological component, and can be reliably diagnosed. I believe this should satisfy anyone’s definition of medical illness.

At the same time, mental disorders represent a form of medical illness unlike any other. The brain is the only organ that can suffer what we might call “existential disease”—where its operation is disrupted not by physical injury but by impalpable experience. Every other organ in the body requires a physical stimulus to generate illness—toxins, infections, blunt force trauma, strangulation—but only the brain can become ill from such incorporeal stimuli as loneliness, humiliation, or fear. Getting fired from a job or being abandoned by a spouse can induce depression. Watching your child get run over by a car or losing your retirement savings in a financial crisis may cause PTSD. The brain is an interface between the ethereal and the organic, where the feelings and memories composing the ineffable fabric of experience are transmuted into molecular biochemistry. Mental illness is a medical condition—but it’s also an existential condition. Within this peculiar duality lies all the historic tumult and future promise of my profession—as well as our species’ consuming fascination with human behavior and mental illness.

No matter how advanced our biological assays, brain-imaging technologies, and genetic capabilities become, I doubt they will ever fully replace the psychodynamic element that is inherent in existential disease. Interpretation of the highly personal human element of mental illness by a compassionate physician will always be an essential part of psychiatry, even in the case of the most biological of mental illnesses, such as Autism Spectrum Disorders and Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time, a purely psychodynamic account of a patient’s disorder will never suffice to account for the underlying neural and physiological aberrations giving rise to the manifest symptoms. Only by combining a sensitive awareness of a patient’s experiential state with all the available biological data can psychiatrists hope to offer the most effective care.

While I am deeply sympathetic to Tom Insel’s position—I, too, certainly want to see an improved neurobiological understanding of mental illnesses—I believe that psychiatry is served best when we resist the lure of epistemic hubris and remain open to evidence and ideas from multiple perspectives. The

DSM-5

is neither a botched attempt at a biological psychiatry nor a throwback to psychodynamic constructs, but rather an unbridled triumph of pluralism. After Insel posted his incendiary blog, I called him to discuss the situation, and together we ultimately agreed to issue a joint statement from the APA and the NIMH to reassure patients, providers, and payers that the

DSM-5

was still the accepted standard for clinical care—at least until additional scientific progress justified its upgrade or replacement.

Since the

DSM-5

’s launch in May 2013, an amazing thing has occurred. There has been a deafening silence from critics and the media. It now appears that the controversy and uproar before its release was focused on the perceived

process

of creating the

DSM-5

as well as on an effort to influence the actual content that made it into the published version. And in the aftermath, while many critics in and out of psychiatry have expressed understandable disappointment about “what might have been”—what if the APA had appointed different leadership, what if the process had been managed differently, and what if other criteria than those officially adopted define a given disorder—it has been gratifyingly clear that health care providers and consumers have been well served by the

DSM-5.

But the far-ranging and heated conflict that played out online and in the media did make one thing salient: Psychiatry has become deeply ingrained within the fabric of our culture, winding through our most prominent social institutions and coloring our most mundane daily encounters. For better or worse, the

DSM

is not merely a compendium of medical diagnoses. It has become a public document that helps define how we understand ourselves and how we live our lives.

The End of Stigma: The Future of Psychiatry

We need our families and friends to understand that the 100 million Americans suffering with mental illness are not lost souls or lost causes. We’re fully capable of getting better, being happy, and building rewarding relationships.

—C

ONGRESSMAN

P

ATRICK

J. K

ENNEDY, ON HIS DIAGNOSIS OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

How come every other organ in your body can get sick and you get sympathy, except the brain?

—R

UBY

W

AX

Hidden in the Attic

I’ve been fortunate to live through the most dramatic and positive sea change in the history of my medical specialty, as it matured from a psychoanalytic cult of shrinks into a scientific medicine of the brain.

Four decades ago, when my cousin Catherine needed treatment for her mental illness, I steered her away from the most prominent and well-established psychiatric facilities of the time, fearing they might only make things worse. Today, I wouldn’t hesitate to send her to the psychiatric department of any major medical center. As someone who has worked in the front-line trenches of clinical care and at the top echelons of psychiatric research, I’ve seen firsthand the sweeping progress that has transformed psychiatry… but, sadly, not everyone has been able to benefit from this progress.

Shortly after I became chair of psychiatry at Columbia University, I was asked to consult on a sixty-six-year-old woman named Mrs. Kim. She had been admitted to our hospital with a very severe skin infection that seemed to have gone untreated for a long time. This was puzzling, because Mrs. Kim was both educated and affluent. She had graduated from medical school and as the wife of a prominent Asian industrialist she had access to the very best health care.

As I spoke with Mrs. Kim, I quickly discovered why a psychiatrist had been called to see a patient with a skin infection. When I tried to ask how she was feeling, she began to shout incoherently and make bizarre, angry gestures. When I remained silent and unobtrusively observed her, she talked to herself—or, more accurately, she talked to nonexistent people. Since I could not engage her in conversation, I decided to speak with her family. The next day, her husband and adult son and daughter reluctantly came to my office. After a great deal of cajoling, they revealed that shortly after Mrs. Kim graduated from medical school, she had developed symptoms of schizophrenia.

Her family was ashamed of her condition. Despite their wealth and resources, neither Mrs. Kim’s parents nor her husband sought any kind of treatment for her illness; instead, they decided to do whatever they could to prevent anyone from discovering her ignominious diagnosis. They sectioned off her living quarters in a wing of their spacious home and kept her isolated whenever they had guests. Despite her having received a medical degree, practicing medicine was completely out of the question. Mrs. Kim rarely left the property and never for any extended period of time—until she developed the skin rash. Her family tried all kinds of over-the-counter remedies hoping that they would take care of the problem. But when it became infected and rapidly began to spread, they became frightened and called the family doctor. When he saw her torso dotted with purulent abscesses, he implored the family to take her to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with a severe staph infection.

Stunned, I repeated back to them what they had just told me—that for the past thirty-some years, they had conspired together to keep their wife and mother shut off from the world to avoid public embarrassment. They unabashedly nodded their heads in unison. I was incredulous—this was something out of a Charlotte Brontë novel rather than twenty-first-century New York City. I told them quite bluntly that their decision to withhold treatment was both cruel and immoral—though, tragically, not illegal—and I urged them to let us transfer her to the psychiatric unit of the hospital so that she could be treated. After some skeptical discussion, they refused.

They informed me that even if Mrs. Kim could be successfully treated, at this point the resulting changes would be too disruptive to their lives and their position in the community. They would have to explain to friends and acquaintances the reason Mrs. Kim suddenly began to appear in public after such a long absence—and who knows what Mrs. Kim herself might say or how she would behave in such circumstances? The Kims perceived the stigma of mental illness as so daunting that they would rather have this once intelligent, otherwise physically healthy woman remain psychotic and incapacitated, her brain irreversibly deteriorating, than face the social consequences of acknowledging her mental illness.