Signor Marconi's Magic Box (32 page)

Read Signor Marconi's Magic Box Online

Authors: Gavin Weightman

The final scene of what the French newspapers called ‘Le Match Drew-Crippen’, in which Inspector Drew of Scotland Yard chased Hawley Harvey Crippen, wanted for the murder of his wife, across the Atlantic. The captain of the liner

Montrose

, on which Crippen hoped to escape with his lover Ethel Le Neve, saw through their disguises and alerted Inspector Drew by wireless.

Montrose

, on which Crippen hoped to escape with his lover Ethel Le Neve, saw through their disguises and alerted Inspector Drew by wireless.

When the

Titanic

began to sink in the early hours of 15 April 1912, the shocking news was relayed across the Atlantic by Marconi operators. Tragically, this message from the liner

Virginian

to the

Californian

, the ship nearest the

Titanic

when it went down, was to no avail. It was sent at 4 a.m., nearly two hours after the

Titanic

sank, but was not picked up by the

Californian

’s lone wireless operator, who was asleep.

Titanic

began to sink in the early hours of 15 April 1912, the shocking news was relayed across the Atlantic by Marconi operators. Tragically, this message from the liner

Virginian

to the

Californian

, the ship nearest the

Titanic

when it went down, was to no avail. It was sent at 4 a.m., nearly two hours after the

Titanic

sank, but was not picked up by the

Californian

’s lone wireless operator, who was asleep.

Marconi was acknowledged worldwide as the hero of the

Titanic

disaster, for without his invention on board, and the wireless distress signals sent out, the fate of the ship would have remained a mystery and nobody would have survived. Many perished because of a lack of lifeboats, a point made in this American cartoon, which has Marconi telling King Neptune he can ‘beat him anytime’ - once the shipping lines provide the rescue boats.

Titanic

disaster, for without his invention on board, and the wireless distress signals sent out, the fate of the ship would have remained a mystery and nobody would have survived. Many perished because of a lack of lifeboats, a point made in this American cartoon, which has Marconi telling King Neptune he can ‘beat him anytime’ - once the shipping lines provide the rescue boats.

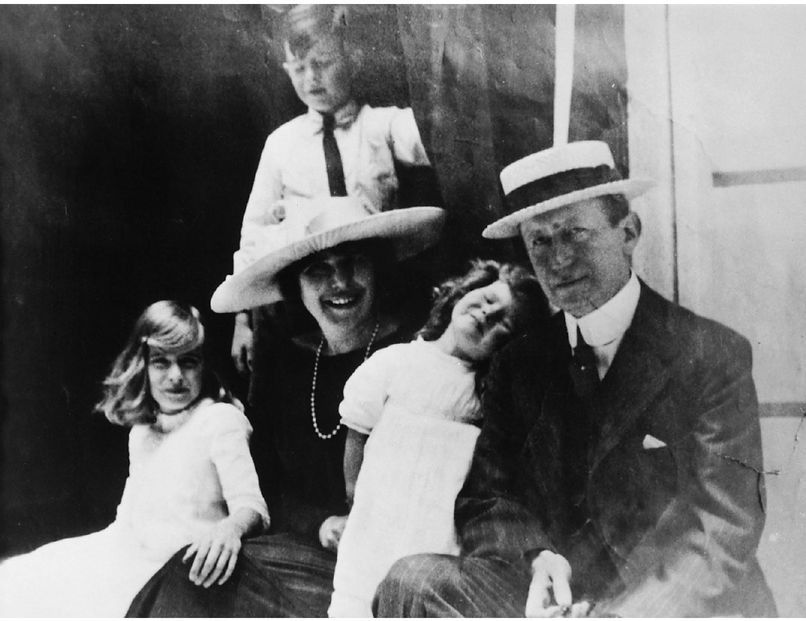

A family snapshot of Marconi with his wife Bea and their three children Degna (left), Giulio and Gioia. Taken around 1920, this was not a picture of domestic bliss, for Bea was not prepared to endure her husband’s long absences and infidelities for much longer; they were divorced three years later, when Bea herself had found a lover whom she wanted to marry.

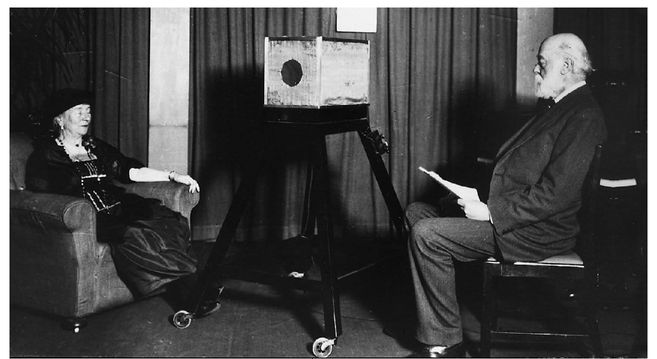

Oliver Lodge, an eminent English physicist and wireless pioneer, making a broadcast in one of the first radio studios in the early 1920s. Though Lodge was sometimes bitter about Marconi’s commercial success, he showed a greater interest himself in spiritualist séances and discovering a proof of life after death than in developing a workable wireless system.

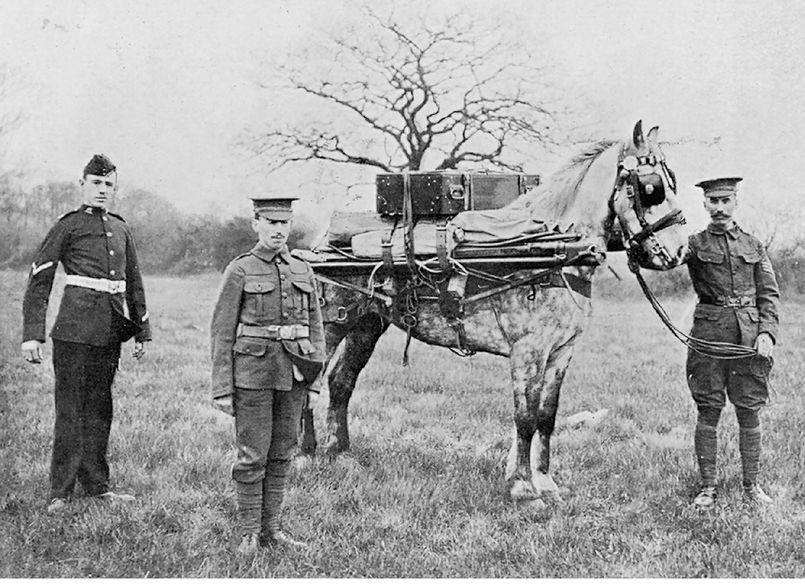

The mobile Marconi wireless kit proudly displayed by British soldiers in the First World War. Wireless was used in the trenches, where a Marconi engineer developed direction-finding techniques, but it had its greatest impact in the decoding of German naval messages picked up by listening stations on the English coast.

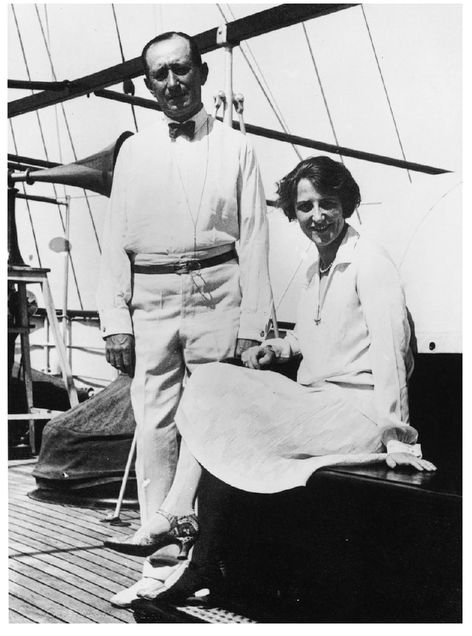

Marconi with his second wife Cristina Bezzi-Scali enjoying the sunshine of his fame on the yacht

Elettra

, which he bought and had fitted out as a floating home and laboratory in 1920.

Elettra

, which he bought and had fitted out as a floating home and laboratory in 1920.

While it was being towed in, the badly damaged

Republic

sank, with the captain and first officer still aboard. They were rescued after a search, and Jack Binns finally steamed back to New York. It was then that his real nightmare began. At the White Star pier a group of sailors and stewards hoisted Binns and Captain Sealby onto their shoulders and carried them through the cheering crowd, amidst a fanfare of trumpets. The

New York Times

and all the other newspapers and magazines had followed the drama, and Jack Binns was treated like a modern pop star. He did his best to shun this unwanted publicity, but the press would not leave him alone. The Marconi Company exploited his celebrity to the full, producing publicity cards with a photograph of Binns, captioned ‘Wireless hero’ and decorated with their own ‘CQD’.

Republic

sank, with the captain and first officer still aboard. They were rescued after a search, and Jack Binns finally steamed back to New York. It was then that his real nightmare began. At the White Star pier a group of sailors and stewards hoisted Binns and Captain Sealby onto their shoulders and carried them through the cheering crowd, amidst a fanfare of trumpets. The

New York Times

and all the other newspapers and magazines had followed the drama, and Jack Binns was treated like a modern pop star. He did his best to shun this unwanted publicity, but the press would not leave him alone. The Marconi Company exploited his celebrity to the full, producing publicity cards with a photograph of Binns, captioned ‘Wireless hero’ and decorated with their own ‘CQD’.

On their way into New York from Nantucket the passengers on the

Baltic

made a collection, the money from which was used to strike commemorative coins of the event. All the crew members of the

Baltic

,

Republic

and

Florida

received medals, but four were struck in gold, one each for the three captains and Jack Binns. On one side of the medal was the distress call ‘CQD’ above a picture of a ship with ‘SS

Republic

’ below, and on the reverse was a citation commemorating the rescue.

Baltic

made a collection, the money from which was used to strike commemorative coins of the event. All the crew members of the

Baltic

,

Republic

and

Florida

received medals, but four were struck in gold, one each for the three captains and Jack Binns. On one side of the medal was the distress call ‘CQD’ above a picture of a ship with ‘SS

Republic

’ below, and on the reverse was a citation commemorating the rescue.

Binns was a reluctant hero, but Guglielmo Marconi basked more happily in the reflected glory of the story: it was his invention that had saved nearly four thousand lives. The only casualties had been three passengers on the

Republic

, who were killed when the

Florida

rammed into their cabins. The magazine

Harper’s

wrote up the drama of the rescue as if wireless had only just been invented: ‘What a wonder-tale it is and how deeply moving - the cry for help thrown out into the air from a mast-tip, and caught, a hundred miles or more away . . . It is a new story; there never was one quite like it before.’

Republic

, who were killed when the

Florida

rammed into their cabins. The magazine

Harper’s

wrote up the drama of the rescue as if wireless had only just been invented: ‘What a wonder-tale it is and how deeply moving - the cry for help thrown out into the air from a mast-tip, and caught, a hundred miles or more away . . . It is a new story; there never was one quite like it before.’

Jack Binns could not wait to get away from New York and back to work. But when he arrived back in Liverpool on the

Baltic

there were again huge crowds, who saw him reunited with his girlfriend. In his home in Peterborough he had to endure a mayoral reception. Finally, Marconi himself presented him with a commemorative watch.

Baltic

there were again huge crowds, who saw him reunited with his girlfriend. In his home in Peterborough he had to endure a mayoral reception. Finally, Marconi himself presented him with a commemorative watch.

From then onwards the Marconi wireless operator was no longer

an intriguing but minor figure who tapped out inconsequential messages for first-class passengers: he was the saviour on the high seas. With his horror of publicity and entirely genuine puzzlement at the adulation he received, Jack Binns proved himself a true heir to the young Marconi, modestly brushing aside the plaudits, insisting that he was only doing his job. None of the boasts of Marconi’s rivals could compare with the triumph of this rescue at sea: it was not long before he would be awarded the highest of international honours for his achievements, and it was probably the rescue of the

Republic

which tipped the balance in his favour.

an intriguing but minor figure who tapped out inconsequential messages for first-class passengers: he was the saviour on the high seas. With his horror of publicity and entirely genuine puzzlement at the adulation he received, Jack Binns proved himself a true heir to the young Marconi, modestly brushing aside the plaudits, insisting that he was only doing his job. None of the boasts of Marconi’s rivals could compare with the triumph of this rescue at sea: it was not long before he would be awarded the highest of international honours for his achievements, and it was probably the rescue of the

Republic

which tipped the balance in his favour.

35

Dynamite for Marconi

O

n 10 December 1896, just two days before Guglielmo Marconi’s demonstration of his magic boxes at Toynbee Hall in London, an inventor with more than three hundred patents to his name died in San Remo, Italy. Alfred Nobel was both an immensely wealthy and an immensely cultured man, a poet who was fluent in Russian, French, English and German as well as his native Swedish. He was born in Stockholm in 1833, the son of Immanuel Nobel, an enterprising builder. The family were bankrupted by an unfortunate accident in which a consignment of construction materials was lost, and Immanuel took them first to Finland and then to Russia, where his wife supported them by running a grocery store. Immanuel had been experimenting with explosives to blast rock for his construction work, and in time he was awarded a contract to provide the Russian army with equipment, including explosives for a crude form of naval mine. The family settled in St Petersburg, where Immanuel prospered and arranged for his children to be educated by private tutors.

n 10 December 1896, just two days before Guglielmo Marconi’s demonstration of his magic boxes at Toynbee Hall in London, an inventor with more than three hundred patents to his name died in San Remo, Italy. Alfred Nobel was both an immensely wealthy and an immensely cultured man, a poet who was fluent in Russian, French, English and German as well as his native Swedish. He was born in Stockholm in 1833, the son of Immanuel Nobel, an enterprising builder. The family were bankrupted by an unfortunate accident in which a consignment of construction materials was lost, and Immanuel took them first to Finland and then to Russia, where his wife supported them by running a grocery store. Immanuel had been experimenting with explosives to blast rock for his construction work, and in time he was awarded a contract to provide the Russian army with equipment, including explosives for a crude form of naval mine. The family settled in St Petersburg, where Immanuel prospered and arranged for his children to be educated by private tutors.

The young Alfred Nobel, whose fondness for literature was regarded by his father as unfortunate, was despatched to various parts of the world to work with chemical firms and academics, and finally settled in Paris. There he learned about the highly volatile explosive nitro-glycerine, and began to experiment with ways of making it serviceable. Meanwhile his father’s Russian business

collapsed and the family fortune was once again in jeopardy until two of Alfred’s brothers revived it by developing the Russian oil industry. Alfred returned to Sweden, where he continued to experiment with nitro-glycerine. It was a very dangerous substance: one of his brothers was killed along with other workers in an explosion before Alfred had found a way of making it safe, producing nitro-glycerine in solid sticks which could only be detonated with a blasting cap. He called it ‘dynamite’, and patented it in 1867. Dynamite made him his fortune.

collapsed and the family fortune was once again in jeopardy until two of Alfred’s brothers revived it by developing the Russian oil industry. Alfred returned to Sweden, where he continued to experiment with nitro-glycerine. It was a very dangerous substance: one of his brothers was killed along with other workers in an explosion before Alfred had found a way of making it safe, producing nitro-glycerine in solid sticks which could only be detonated with a blasting cap. He called it ‘dynamite’, and patented it in 1867. Dynamite made him his fortune.

At the age of forty-three, Alfred Nobel was still single. The French novelist Victor Hugo described him as ‘Europe’s richest vagabond’. Desperate for a relationship, he put a lonely hearts advertisement in a newspaper: ‘Wealthy, highly educated gentleman seeks lady of mature age, versed in languages, as secretary and supervisor of household.’ The post went to Countess Bertha Kinsky, an Austrian aristocrat who stayed with Nobel for only two months but remained a friend for the rest of his life. She married a fellow Austrian, Count Arthur von Sutter, and became an activist in the European peace movement towards the end of the nineteenth century. Nobel, though famous for his invention of dynamite, became a supporter of the peace movement - explosives were more widely used for blasting rock for roads and mines than in warfare. He always retained his interest in literature and poetry.

Other books

Eppie by Robertson, Janice

The Universe Maker by A. E. van Vogt

In the Shadow of Swords by Val Gunn

Moonlight Becomes You: a short story by Jones, Linda Winstead

What She's Looking For by Evans, Trent

The Reunion: Emma's Vacation (The Starting Over Series) by Rose, Angelina

Ruthless by Sara Shepard

Orpheus and the Pearl & Nevermore by Kim Paffenroth

Summer of the Gypsy Moths by Sara Pennypacker