Silverbeach Manor (6 page)

Authors: Margaret S. Haycraft

Tags: #romance, #romance historical, #orphan girl, #romance 1800s, #romance 1890s, #christian fiction christian romance heartwarming

What

have the three years brought within Polesheaton, Miss Temperance

Piper, and the little general shop? It would be useless to ask

Pansy, for she knows not. Whether she

cares

or not only her secret heart can tell. The life in the

village shop seems to her now like a long-past dream, and though

her aunt, in reply to her letter, sent a few tender lines of love

and blessing, Pansy dared not offend Mrs. Adair by continuing the

correspondence, so that aunt and niece have drifted apart surely

and utterly now.

Pansy is very

much in love -- how could she fail to be, after the long teaching

and training of overdrawn and sensational love-stories upon Miss

Piper's counter? She was prepared to fall in love from the hour she

left the home of her childhood, and Cyril Langdale has continued

ever since her hero, her prince, her ideal.

"I

know

he cares about me," she

tells herself sometimes, blushing even at the thought. "He has

never spoken plainly, but his eyes have a language of their own. He

has sketched and painted me again and again, and did he not once

call me 'darling' when we were rowing in the moonlight? And does he

not hold my hand, and did he not ask me to take care of myself,

when my throat was sore, for

his

sake? I

only just caught the whisper, but I am sure those were the words he

said.

"He is so

good, so clever, so tender, so handsome -- what a happy, happy girl

I am! Mrs. Adair is fond of him, and she encourages his visits. I

know she would let us be engaged. The course of true love will run

smooth in our case. I do think I am the most fortunate girl in all

the world."

It would

seem far less romantic to Pansy if her hero proposed to her

otherwise than with his impressive dark eyes. Her heart relies

absolutely upon his devotion, and if she prays at all in these

glittering days, the name of "

Cyril"

is

that which fills her petitions.

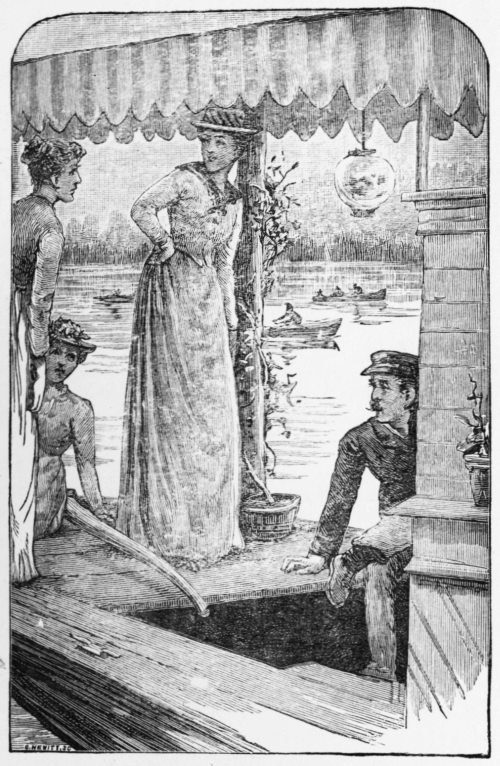

Never while

she lives will she forget the day that scatters her fairy dream for

evermore. She is at her brightest and happiest in Mrs. Adair's

houseboat, witnessing a festive regatta on the river, when May

Damarel, a girl with whom she is very friendly, accosts her with

the exclamation, "Why, there you are, Pansy. I have wanted to get

you to myself ever so long. I have something marvellous to tell

you. Wonders will never cease. A regular old bachelor is going to

be married."

"Old Mr.

Henry?

"

asks Pansy, looking with

amusement at the endeavour of a young-looking spinster in the

company to get an elderly bachelor to explain the regatta for her

benefit. "Well, perseverance deserves success."

"No, no;

somebody we know much better, Pansy. Guess again."

"We do

not know many

old

bachelors. Do you mean

the vicar?"

"Why,

child, he is nearly ninety. The one I mean is not really

old,

but people have expected him to marry for

years, and have grown accustomed to looking upon him now as a

confirmed bachelor."

The thought

flashed across Pansy's mind that Cyril Langdale may have hinted to

his friends that he has some hope and idea of marrying. She blushes

deeply, and tells May she is no good at guessing, while little

throbs of trembling joy awake new sweetness within her heart.

"Well, I

mean Cyril Langdale. Who would have thought of

his

getting engaged? Can you guess the lady, I

wonder? "

Pansy thinks

she can, but only leans against the flower-wreathed pillar of the

boat, and looks smilingly out to the sunny waters.

"Of

course it is that American widow, Mrs. Tredder. I suppose she is

the handsomest woman on the river today, and you know he worships

beauty. Then they say her husband was almost a millionaire. Mother

says she has never seen more valuable diamonds than Mrs. Tredder's.

It is a fortunate marriage for

him,

for

people say his tastes are very expensive. You have seen Mrs.

Tredder, have you not, Pansy?"

"Yes ... we

saw her at his studio one Sunday," answers Pansy slowly, who was

deeply struck at the time by the widow's wonderful beauty, but had

not the slightest notion that Cyril Langdale was paying his homage

in that direction. "I think he would have told us," she says, with

a face that has lost its roses. "He never mentioned Mrs. Tredder

much. I believe you are making a mistake."

"Am I? Why,

they are always together in London, and she is ever so proud of his

genius. He is painting her for next year's Royal Academy. Why,

speak of an angel -- there they are, both of them, in Sir Patrick

Wynn's gondola! How lovely she looks, leaning back against the

crimson cushions! Isn't the gondolier handsome, Pansy -- an ideal

Venetian? I do wish we had a gondola."

"How hot it

is! The sun makes my head ache," says Pansy, moving away from her

friend and shading her eyes with her hand.

***

It is true that

the beautiful widow, with her diamonds and dividends, has been

successfully sought by the beauty-loving artist, and that he is

complacently conscious of victory where many another has met with

repulse. At the same time, his conscience is not wholly easy

concerning Pansy Adair, with whom he has undoubtedly flirted, and

whom he might have seriously fancied if he could be certain her

patroness would endow her with Silverbeach Manor and her wealth. He

glances at Mrs. Adair's houseboat, and is rather relieved to notice

the smiling nod with which Pansy responds to his salutation, and to

hear her laughter ring across to the gondola as she eats

strawberries and cream in the midst of a light-hearted throng.

"Permit

me to congratulate you, Mr. Langdale, and to wish you happiness,"

Pansy says, looking into his face when, later on, he brings

his

fiancée

on board the

houseboat.

Mrs. Tredder

dazzles all around by her perfect costume and bewitching face, and

is very friendly to Pansy and invites her to visit her in Hyde

Park. Langdale becomes quite at his ease, so successful a curtain

is Pansy's pride; but the girl feels today that her very heart is

broken.

For a time her

health and spirits suffer considerably from the shock of this first

sharp sorrow. She cannot accuse Cyril Langdale of desertion, for he

never belonged to her openly, and has always enjoyed the character

of being quite a "lady's man", but subtle looks and tones, only

known to the two of them, undoubtedly gave her reason to believe he

cared for her in sincerity. It takes her a long, long, bitter time

to realize that he is about to become the husband of one who, till

almost recently, was a stranger. She is realizing that even with

money to spend and spare, and amid lives that fare sumptuously

every day, trouble, and heart-sickness, and disappointment may not

be shut out.

"I will find

rest in music," she decides, struggling against the lethargy that

steals over her, and that no tonic seems to dispel. "I have read

that there is nothing like a hobby to banish sad thoughts and make

troubled hearts content. I will live for my violin. I will put

aside my poor, lost dream of love, and be satisfied with fame. Mrs.

Adair would never let me perform professionally, but I will be the

best-known amateur violinist in society. It must be sweet, it must

be glorious to be famous. I will work hard, I will strive hard to

be great."

***

Pansy did

indeed strive hard, and became as an honoured guest in the drawing

rooms of ladies of title. Mrs. Adair is filled with pride with the

eloquent praises (and silences even more complimentary) that follow

Pansy's performances, while the society papers bestow upon her such

glowing tributes as this:

Among the brilliant throng at Lady ----'s or the Duchess of

So-and-So's, might have been seen one of the queens of London

society -- Miss Adair, of Silverbeach Manor, the talented amateur

violinist. This beautiful and gifted young lady was, as usual,

attired in the perfection of taste, and elicited the most

enthusiastic applause by her rendering alike of classical studies

and lighter

pieces

on the exquisite instrument which has been presented to her

by Mrs. Adair. We understand that this lady objects to Miss Adair's

photographs being publicly sold; otherwise the fair face and form

of one so universally admired would before this have been seen amid

the portraits of society leaders and types of beauty.

Pansy used to

read such words long ago, about ladies moving in a world that

seemed further from her then than Paradise itself. How she envied

the fashionable beauties of whom such descriptions were penned. But

now the homage is so customary that it only wearies her, and she

begins to understand that society, once the acme of her ambition,

is apt to prove, to those who have too much of it, a little

monotonous and tiresome.

Surely the

zenith of Pansy's musical glory is reached when a special request

reaches Silverbeach that she will play before Royalty, and Mrs.

Adair in her excitement sends to Paris for a dress for her adopted

child, who is robed for the occasion in white and silver brocade,

draped with rare old lace, the flowers at her shoulder being the

choicest orchids.

Looking at

herself in the tall mirror before her departure, Pansy gives no

thought to the elderly figure of her aunt, baking, washing, sewing

hour by hour in a dingy village shop, tireless, often sleepless,

that a little orphan girl might be comfortably fed and clad. She

shines resplendent before Royalty, and excels herself as to her

playing, till the aristocratic hearers are enraptured, and a

certain gracious Princess speaks to her kindly and admiringly, and

gives her a photograph of herself with her autograph in a charming

frame.

But the

excitement has proved too much for Pansy. To be famous at the cost

of one's health is glory dearly bought, and whether her musical

triumphs or her heart-trouble assist in the breaking down, she

falls ill, and many weeks elapse before the Silverbeach doctor, a

specialist as to nerves, will permit her to leave her bed for the

couch in Mrs. Adair's snuggery.

It is while

lying on her couch that vague, tender yearnings begin to stir

within her for the love that wrapped her childhood. The face that

comforted her early sorrows, smiled brighter sunlight into her

joys. She cannot forget the little gabled roof of the village shop,

the humble, old-fashioned garden, the homely, cosy kitchen. The

scene comes back before her, and instead of the cushioned lounge,

the artistic curtains about the mantel-board, the musical clock and

bronze Tunisian figures in the room where she is resting, she sees

once more Aunt Temperance putting on her glasses to sort the

letters, Deb weighing sweets and cheese with attentive face and

careful hand, and her pretty canary, once her pride and care. A

great longing seizes her to receive a letter from her aunt again,

to send them a little help, to let Aunt Temperance know and

understand she is not unforgetful, ungrateful.

"She may be

ill -- in need," says Pansy, brokenly, venturing in her privileged

convalescence to breach the long-avoided subject to Mrs. Adair.

"Aunt Temperance denied herself so much to provide for me. I have

money. May I not send her a little?"

"You may send

her a five pound note anonymously," says Mrs. Adair, yielding this

point because of the low state of Pansy's nerves; "but the

correspondence between you has ceased once and for all. Miss Piper

is no longer your aunt. You seem to forget that your name is Adair

and your home is Silverbeach Manor. You have made your choice, and

it is wrong to look back discontentedly. You have nothing more to

do with your past as long as you live. You must understand this,

Pansy, if you mean to continue my charge, my comfort, my child. I

will accept no divided affection."

So the five

pound note goes anonymously to Miss Temperance Piper, Polesheaton

Post office; and none at Silverbeach is aware that it is returned

to the Dead Letter Office with the inscription, "Gone away --

address not known."

6

Pansy's Predicament.

THE months that

follow are full of what Pansy Adair once looked upon in vision as

pursuits most delightful and bewitching. Mrs. Adair has some secret

notion that Cyril Langdale's marriage may have had something to do

with Pansy's indisposition, and she resolves to divert the mind of

her adopted child who has become very dear to her, by a round of

pleasure in its most brilliant aspects.