Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir (17 page)

Read Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir Online

Authors: Linda Ronstadt

Sound check in London, Dan Dugmore playing guitar.

12

Getting Restless

M

Y LIFE HAD SETTLED

into a fairly predictable routine. I’d make an album a year, which would take a few months to complete, and the rest of the time we would play one-night stands all over the country. By now my records were selling so well that instead of playing in intimate spaces like the Troubadour, I was being booked into hockey arenas and outdoor pavilions with huge audiences. The sound in those enormous places was kind of like being in a flushing toilet with the lid down. There was so much evil slapback ricocheting off the walls and ringing in the rafters, I’d swear I could still hear the lead guitar solo from the band that had played the week before. Those places were filled with zombie sound that simply refused to die; it just grew dimmer with time. In addition to that, people were milling about, passing joints, and drifting off in search of a hot dog or a cold beer at the concession stands that ringed the upper tiers.

Now, I was both delighted and deeply grateful that the records were selling and people were filling up those horrible-sounding arenas to hear me sing, but I couldn’t help feeling that somehow both the audiences and the performers were getting a raw deal. The audience was getting a sound mix that was so distorted by the acoustics of the building that any delicate passages or musical subtleties were lost. This had a sinister effect on the way we created the music. Since they couldn’t hear anything but loud, high-arching guitar parts and a cavernous backbeat, and because they didn’t want to hold still for anything they hadn’t heard on

one of the albums, we began to tailor our recordings, consciously or not, to that big arena sound. This meant that all the really well-crafted and more delicate material, like “Heart Like a Wheel” or “Hasten Down the Wind,” had to be slipped in between something that could survive the onstage acoustics.

I stubbornly hung on to those songs and layered them into the recordings like pills in hamburger. I knew that a melodic ballad was a better vehicle for my voice. It would allow me to mine a much richer emotional vein than what I could get from what I used to call a “short-note song.” By that I meant a kind of uptempo song that a rock band would write to fit over a catchy riff, giving it something to do until the lead guitar player got to play his Big Solo. This kind of approach produced some excellent music from bands like Cream and the Rolling Stones, but even the musicians from those bands would regularly complain that they missed the musical heat of their club days and wished they could play in more musically sympathetic settings. Those boomy arenas hammered all the subtleties out of rock and roll as well and then proceeded to play midwife to the birth of heavy metal.

Since there are always talented players in these emerging categories, no matter how grating they may be to the ear of the more traditionally inclined, I was not surprised when the heavy metal band Metallica achieved a style that was huge and orchestral in its guitar textures, showing itself to be perfectly capable of producing beautiful melodies with unusual, finely constructed harmonies. My son at twelve was a devoted metal shredder, and once, while I was listening to him break down a Metallica song and then reconstruct it on the neck of his own guitar, I mentioned that I thought their stadium-size guitar textures resembled a symphony orchestra. He gave me a look of withering teenage scorn. I was vindicated when Metallica brought out

an album it made with the San Francisco Symphony under the direction of Michael Tilson Thomas. All this is a long way to demonstrate that musicians reach for a rich acoustical setting like a plant reaches for light, and I was no exception.

Something else that made me sad about the action shifting out of the clubs and into the arenas was the fact that artists didn’t get to see one another perform as much as when the folk rock music scene was centered on L.A.’s Troubadour or New York’s Bitter End. The limited space of the Troubadour put the bathrooms in a back-hall area off the performance space. That meant everyone from the bar had to travel through the room where the stage was in order to visit the plumbing. Even if you were an up-and-coming hopeful hanging out in the bar but too broke to pay the admission fee, you could get a rich sampling of what was happening on the stage every time nature insisted. If you had been hired in the past by owner Doug Weston to play at the Troubadour, you got free admission, so when somebody interesting was playing, we veterans would crowd the staircase and the upstairs balcony night after night to see our favorites. I remember seeing artists like Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, the Flying Burrito Brothers, George Carlin, and Steve Martin play every night of a two-week engagement, two shows a night, and three on Friday and Saturday nights. This way, artists got to see a wider arc of another artist’s talent, and some vigorous cross-pollination of musical styles was the happy result.

Seeing each other’s shows in arenas didn’t happen so naturally. The tickets were way more expensive, which left out the newbies, there was no place to hang out and mix socially, like the Troubadour bar—unless one had rare and privileged access backstage—and parking was a hassle. And then there was lousy sound, so we couldn’t listen and dissect the music like we had been able to do in the smaller settings. In short, it became less

likely for the artists to trip over the influence and inspiration of one another than it had been before.

I felt some stagnation setting in, and the relentless touring and endless repetition of the same songs over and over again promoted a creeping awareness that my music had begun to sound like my washing machine.

A promotional tour that took us to Great Britain, Germany, and France in the late 1970s jolted us back into the forgotten reality of what it was like to play in smaller, dedicated music venues. I was not particularly well known in Europe, so we were playing in medium-size theaters with proscenium stages and lots of chubby-faced cherubs in bas-relief cavorting around the walls. The cherubs and other fussy design elements, in addition to delighting my Victorian sensibility, softened the parallel surfaces of the theater walls and sweetened the sound. Finally, the dream I held so dear as a child had materialized: I was singing on a real stage in a real theater with a curtain. I was inspired.

The inspiration was short lived. We were soon back in the USA, pounding the same old circuit in the same distinctly uninspiring arenas. Add to this the gnawing loneliness of life lived perpetually in motion, with not enough time in any one place to nurture relationships or build trust. I was beginning to feel miserable. And trapped.

One night we were playing in Atlanta. We had spent the afternoon fooling around in the little shops that had been established in what is called Underground Atlanta, the recently excavated, fire-charred remains of the pre–Civil War city. Big, smudgy, black-ringed eyes were in style then, and I found what seemed like a particularly exotic way to achieve it in one of the little shops. It was an ancient cosmetic called kohl—new to my experience—which

was some kind of black mineral ground into a fine powder, and recently shipped in from India. There was also a blue one, which was a departure for me, but I figured if I couldn’t change my life so easily, I could at least change the color of my eye makeup, so I bought that too. It was packaged in a little clay pot with a pointed wooden stick screwed into the lid to use as an applicator.

I was hot to try it out and went immediately to the dressing room of the place we were playing (another arena) and started to smear the stuff around my eyes. The applicator stick and powdered medium were unfamiliar and clumsy for me to use, and I had accidentally dotted my cheeks with what looked like the blue measles. I finished the job of cleaning off all the little stray blue blobs and wondered what I was going to do for the forty-five minutes until I had to sing. I had finished the book I kept in my purse and was scowling at the concrete floor—wishing we were still in a European theater with cherubs and that I didn’t have to face an all-night drive in the bus after the show—when someone knocked on the door, bringing me out of my little sulk. It was one of the security guards, who handed me a book that someone had sent backstage with a note attached saying that it was something he or she thought I might like. “Oh goody!” I thought. “Now I won’t have to be bored.”

I looked at the cover:

The Vagabond

, by Colette. “Never heard of this book,” I thought. Never heard of Colette, either. She had just one name. Like Cher.

I opened the book and began to read. The story is set in France in 1910. La Belle Époque! My favorite era! There is a woman about my age who performs in music halls sitting backstage in her dressing room. She is applying blue greasepaint circles around her eyes, and some of it has run down her face. Blue for her too? She also uses kohl. Kohl again! I just heard of the stuff that afternoon.

What else? She is kind of bored. She has already read the book she has with her. She is waiting to go onstage and do her act. She has lost the inspiration to continue in her career as “a woman of letters” and is trying to establish herself as “a woman on the stage.” Things are not going as well as they could, and she knows that she is “in for a bad fit of the blues.” She is thinking about her dog and her kind-of-awkward boyfriend whom she misses somewhat. There is a knock on her door . . .

I have a beloved Akita dog and an awkward boyfriend somewhere. I feel that I’m “in for a bad fit of the blues.” I can relate!

I finished the book that night on the long bus ride. I started to ponder: How can I work in a more theatrical setting, in smaller theaters, and not a different place every night?

13

Meeting Joe Papp

Photo by Martha Swope.

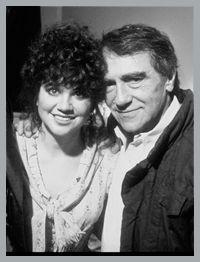

With Joe Papp backstage at the New York Public Theater during

La Bohème.

I

PICKED UP THE

next available phone and called my pal John Rockwell in New York to whine about my predicament. John wrote about music for

The New York Times

for more than thirty years and is one of the rare critics who can write with equal authority about both classical music and contemporary pop music. We met in 1973, when he came to my apartment on Beachwood Drive in the Hollywood Hills to interview me. He noticed that I had a book on my shelf called

Before the Deluge: A Portrait of Berlin in the 1920s

, by Otto Friedrich. (Yes, I lent the book to Jackson Browne, who wrote a good song with the same title. This is done frequently and is legal.

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress

, the title of a 1966 science-fiction novel by Robert Heinlein, comes immediately

to mind. The great songwriter Jimmy Webb loved the title and appropriated it for a song that I later sang on my album

Get Closer

.)

Before the Deluge

was about the Weimar Republic in Germany, just as Hitler was coming to power, and all the missed opportunities that might have stopped him. I had become fascinated with the tragedy of this era, as well as the glamour of prewar Berlin, the architectural innovation, the declining importance of virgin brides (no dowries in a bad economy), the gender-bending clothing styles, the hair and makeup styles, and the wonderful music (Kurt Weill, the Comedian Harmonists). David Bowie was beginning to experiment with one exotic image after another, and in the mid-1970s his look seemed eerily similar to that earlier time. I wondered then if we were heading into our own little version of the Weimar Republic here in the United States, to be followed by the harsh realities of fascism and aggressive imperialism.

Rockwell, who lived in Germany as a child, earned his PhD in German cultural history, and wrote his thesis on the Weimar Republic, is a fountain of information, and we bonded. The day I called him to complain so bitterly about my stagnant state of mind and need for angels in the architecture of my place of employment, he suggested that the next time I came to New York, he would like to take me to meet a fellow named Joe Papp. “Who is Joe Papp?” I asked. Joe Papp, intoned Rockwell, was a brilliant theater man who had revolutionized the interpretation of Shakespeare by insisting it be made accessible across cultural, economic, and social lines, using racially diverse casts and presenting it to the public at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park for free. He also was not afraid to bring in people from other areas of show business. Maybe he had some ideas about what to do with me.