Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir (16 page)

Read Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir Online

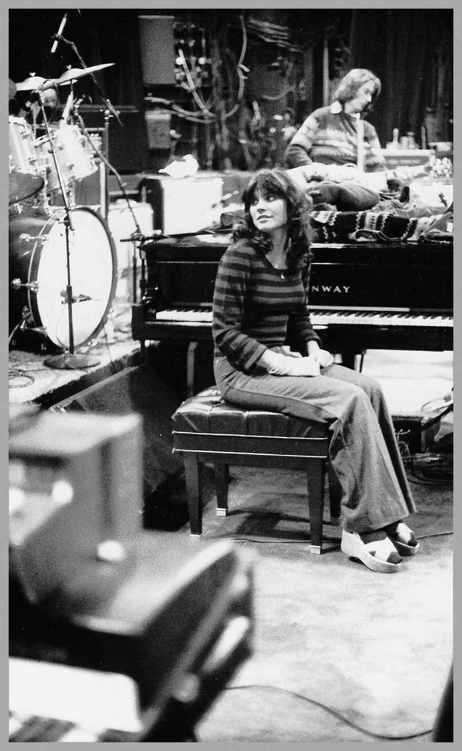

Authors: Linda Ronstadt

In American traditional music, there are lots of trio configurations for men but not so many for women. Bluegrass singing has been a man’s domain, and rightly so. It is the attempt to push the male harmonies so high—a wail one notch below a scream—that gives the vocal blend an edge and a tension creating what is called the “high, lonesome sound.”

Styles of harmonizing for women seem to me no less urgent and a great deal more reflective. Both men and women worked hard in the rural communities that gave us our rich treasury of Americana music. For men, it was the bone-crushing work of farming, mining, or building railroads and bridges. For women, it was seven days a week of laundering, cleaning, looking after children, and putting three meals on the table. When they did have some time to steal away and play music, I imagine them sitting in a tidy parlor, sharing their sorrows, joys, and disappointments with sisters or bosom friends. They would be playing whatever instruments and at whatever musical proficiency they were able to acquire; then they would scurry back to the unrelenting business of running a household.

The sound we were making wasn’t bluegrass and it wasn’t honky-tonk country music.

It wasn’t even restricted to what Dolly referred to as “old-timey music,” as we also wanted to explore more recently written material like the songs of Kate and Anna McGarrigle, or Linda Thompson, who was making remarkable records with her then husband, British musician Richard Thompson. We came to regard it as “parlor music”—something subtler and more genteel than bluegrass, honky-tonk, or the current pop music we heard on the radio.

We decided we would like to make a record together. While the merits of this idea seemed obvious to us, it was not immediately apparent to our respective managers or record companies.

There had been a number of attempts to forge and record “supergroups,” which were composed of hugely successful and easily recognizable names from various rock bands. Sometimes the music from these groups turned out well, and sometimes not. We weren’t trying to exploit the fact that we were three established names. We wanted to do it because at our deepest level of instinct, we suspected musical kinship.

Of course, trying to sort out the conflicts and demands of three different careers being represented by separate managers, agents, and record companies made singing together professionally almost impossible. We never did manage to align the planets for a concert tour, but we eventually carved enough time out of our schedules to make two albums over the years.

Musically, I found the experience very satisfying, with each of us bringing something different to the sound. Emmy usually found the best songs. Dolly’s Appalachian style, with its beautiful ribbon-bow embellishments, lent an authenticity to the more traditional songs. Dolly and Emmy are both natural harmony singers, but the process of sorting out the more difficult harmony

parts usually fell to me. We would try singing the songs in every vocal configuration, shifting around who sang high or low harmonies and who sang lead, and then choose what sounded best for that particular song. We also could duet successfully in any combination: Emmy and I, Dolly and I, or Dolly and Emmy. My favorite approach, which we used, for example, on “My Dear Companion,” was for Emmy to start the lead, me to join her with a harmony underneath, and then have Dolly soaring above, dipping and gliding like a beautiful kite. I found I was able to sing with them in ways that I was not able to do by myself. I am seldom happy listening to my own recordings because I will hear something I think I should have done better, but the sound that the three of us made together seemed altogether different from our individual sounds and could be listened to with a rare sense of objectivity.

It was 1987 by the time we sorted out the logistics of synchronizing three busy careers and released

Trio

. Our earlier attempt to make a record when we first started trying to sing together in the mid-1970s was disappointing and never released. We each chose favorite tracks from those sessions and incorporated them into our individual projects. Still, we wanted very much to release an entire album of the three of us singing together. With Dolly between recording contracts, and Emmy and I each signed to labels that belonged to the Warner Bros. conglomerate, it seemed like an ideal time to resurrect the idea. We decided to have George Massenburg produce, as he had shown extraordinary sensitivity to the recording requirements of acoustic instruments when he worked with John Starling and the Seldom Scene. We called Starling right away and asked him to come out to play guitar. Emmy and I had great trust in John’s musical sensibility, so we also asked him to help us shape our vision of what the trio should sound like.

As usual, Emmylou came in with an armload of beautiful songs. Mostly traditional in style, they also included the unlikely choice “To Know Him Is to Love Him,” the Teddy Bears’ 1958 classic written by Phil Spector. We recorded it with a band that we had assembled from the community of virtuoso acoustic string band instrumentalists that Emmy and I had long admired and played with. They included Mark O’Connor playing mandolin and guitarist Ry Cooder playing a seductively indolent, sleepwalking electric sound that only he can coax out of his equipment. We also had British guitarist Albert Lee and my cousin David Lindley. My old Stone Poneys bandmate Kenny Edwards played a Ferrington acoustic bass guitar. With Emmy’s angelic, soaring lead, “To Know Him Is to Love Him” was a number one country hit for us. Emmy also suggested Linda Thompson’s withering, sorrowful ballad “Telling Me Lies.” It, too, succeeded as a single, and both songs won awards.

Dolly, Emmy, and I had a lot of fun recording together, and we even managed to squeeze a few television appearances and one later album into our three already overbooked schedules, but finding time to tour together was impossible, so we felt lucky to have such a musically satisfying experience and let the rest of it go.

In 1987, with artists like the Beastie Boys and Bon Jovi topping the charts, it was easy to understand why the record companies were scratching their heads trying to figure out how to sell such an eclectic stew. Dolly was no longer with her longtime label, RCA Records, so that left my company, Elektra/Asylum, and Emmy’s company, Warner Bros., to figure out which one would release it. I suspect the negotiations more closely resembled a game of hot potato than it did a determined competition for a desired product. It was eventually decided that since Warner had a country division, it would take our record and construct an ad campaign aimed at the country music market.

To make matters more difficult, the marketing geniuses on the corporate side of the country music labels had decided to start using focus groups to test their products before they were developed or released. An example of this would be to ask the focus group whether they liked sad songs or happy songs. “We like happy songs!” the focus group would chirp, and the word would go back to the writers and producers to come up with “happy” songs to record. This made it especially hard on the songwriters, who rarely feel a need to write when they are happy, as then they are busy luxuriating in the pleasure of happiness. When something bad happens, they want to find a way to transcend it, so they write a song about it. When Hank Williams, one of the greatest and most successful country artists of all time, wrote a song like “Your Cheatin’ Heart” or “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” he wasn’t writing “happy” songs, yet they made the listener feel better. The listener could feel that someone else had gone through an experience similar to the listener’s own, and then went to the trouble and effort to write it down accurately and share the experience like a compassionate friend might do. In this way, hearing a song like “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” could make the listener feel better, or “happy.” Our record, with songs like the traditional “Rosewood Casket,” which told a story of a dying and heartbroken sister’s last request, didn’t meet the focus group’s requirements.

Jim Ed Norman, who had been the keyboard player in Shiloh, the band Don Henley played in before the Eagles, had very recently been made head of the Warner Bros. Records’ country music division in Nashville. I suspect he had as little patience for the focus group approach to marketing music as we did. He seemed happy that the project had bounced into his lap and did his best to promote it.

When

Trio

was released, it went to number one on the country

chart and remained there for five weeks. It rose to the Top Ten on the pop album chart and won a Grammy and an Academy of Country Music Award. It had four country hits, including the number one “To Know Him Is to Love Him.” Within a year, it was certified platinum.

In the winter of 1979, the West Coast was hit with one ferocious rainstorm after another. The Pacific Coast Highway collapsed in a series of spectacular mudslides, making it impossible for me to drive home for weeks at a time. I found that I could take a long detour through Las Virgenes Canyon, but it also was subject to mudslides. This went on for three months, as the overburdened California Department of Transportation tried to fix a road that, due to inherent geological instability, never should have been built in the first place.

Trapped in Malibu, I watched the high waves strip the sand off the beach in front of my house, which was built with no foundation. Most of the houses in Malibu Colony have a glass-enclosed room, called a teahouse, which extends from the house proper out onto the beach. One night the waves were so high that they swept away the last of the sand from under my teahouse. With no support beneath, it splintered off the main house, my sofa cushions churning in the seawater as though they were in a giant washing machine. I realized I had broken the first rule of the desert: never buy a house in a flood plain.

I was keeping company with then-governor Jerry Brown, and he came out to look at the damage. By this time, the newspapers had begun to speculate on whether the governor was going to spend state money to protect his girlfriend’s house. Precisely because of such speculation, Jerry had already decided not to, so I loaded my furniture and belongings into a moving van and

sent them to storage, as I knew my house would surely collapse with the next surge of waves. Meanwhile, the other Malibu residents had heard that he wasn’t going to spend money to protect the Colony because I lived there and felt they were being treated unfairly. After all,

they

weren’t his girlfriend. I was expecting people to show up with torches and pitchforks, demanding his hide. Poor Jerry was being cornered in a situation he didn’t cause and for which he couldn’t offer a permanent solution.

Eventually, after Jerry talked at length to residents up and down the beach, the National Guard was called in to sandbag, and the houses were saved. I decided to look for a house in town, far from the recurring menace of the waves. I left Malibu believing that the California Coastal Commission was correct in insisting there be no new building on the beach, as the houses are too vulnerable, and development can disrupt the natural distribution of sand, resulting in precisely the situation I experienced. I also believe that the beach should not be owned as private property and the public should have unrestricted access to it.

I found a pretty house on Rockingham Drive in Brentwood that was designed by the architect Paul Williams, whose work I have long admired. It had a blue slate roof, lots of bedrooms for guests, and a pretty garden for my two Akita dogs to run. Adam’s songwriting career had begun to heat up, and he moved to Santa Monica. Nicolette eventually moved into the Rockingham house with me. So did our pal Danny Ferrington, a luthier from rural Louisiana who built beautiful guitars entirely by hand. He made them at the behest of various musicians who sought him out to build their dream guitars. They included Johnny Cash, Keith Richards, George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Richard Thompson, and Ry Cooder, to name a very few. He would customize them by incorporating design suggestions from the musicians, accommodating both their visual and musical requirements. The guitars

always sounded wonderful, with the acoustics tweaked for the particular playing style of the individual, whose technique and sound he knew in intimate detail. His brilliance lies in the fact that he can make the musician’s wildest decorative fantasy seem tasteful. He made a tiny guitar for me that I could play while riding on our tour bus. Constructed of rosewood, ebony, spruce, abalone, and mother-of-pearl, it had a normal width neck and a small body for fitting in cramped spaces. The finished piece was elegant, even though I insisted the design elements include bunnies and tweeting birds. To each her own.