Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon (36 page)

Read Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon Online

Authors: Stephan V. Beyer

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Religion & Spirituality, #Other Religions; Practices & Sacred Texts, #Tribal & Ethnic

Sweat Bath

The sahumerio, steam bath, is also used for removing sorcery from the skin

and, by its penetrating qualities, may drive out invasive pathogenic objects

as well. The steam bath is applied by having the patient sit in a chair, naked, wrapped in a blanket or poncho. Water with plants in it is heated almost to a

boil, the bucket of steaming hot water is placed beneath the chair and inside

the hanging blanket or poncho, and the steam is allowed to rise. Steam can

also be applied to the face and head the same way, with a towel or cloth draped

around the head, while the patient bends over a basin of steaming water.

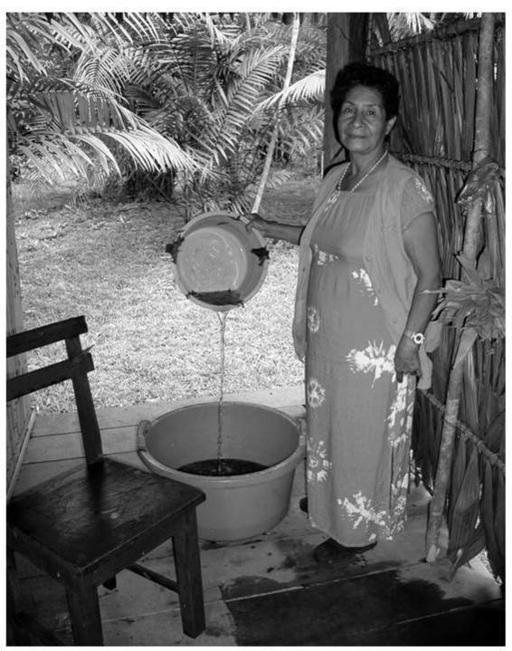

FIGURE 7. Dona Maria with her healing and cleansing bath.

Among indigenous peoples of the Upper Amazon-Shipibo, Anashinka,

Machiguenga-a practitioner called a vaporadora, almost always a woman,

makes use of a similar sort of herbal steam bath.,' Vaporadoras are not shamans but are rather like parteras, midwives, or hueseros, bonesetters-medical specialists who do not use sucking and blowing tobacco smoke in their

practice.

This steam therapy is practiced by putting red-hot rocks or axe heads into a

pot with water and herbs and then having the patient squat over the pot wearing a cushma, which keeps the steam inside, like a tent. Afterward, the vaporadora throws away the water, examines the herbs remaining in the pot, and

often finds some pathogenic object-a nail, a thorn, a piece of bone or charcoal-that was expelled from the patient.19 "With my medicine I soothe the

patients," says Susana Avenchani Faman, a vaporadora. "Through the spirit

of the leaves that are boiled for steam, the patient will be calmed.""

Dona Maria was something of a specialist in steam baths. The plants she

used were almost always plantas brujas, sorcerer plants, dark in color. Dona

Maria frequently called these plants morado, literally "purple" but generally

meaning dark-dark-skinned people in the Amazon are morado-although

some of these plants are, in fact, purplish in color. These sorcerer plants she

frequently paired with another plant she called verde, literally "green" but here

meaning generally lighter in color-for example, the plant called, variously,

pinon negro, pinon rojo, and pinon colorado, dark pinon, as opposed to pinon

blanco, light pinon, which she called pinon morado and pinon verde, respectively.

Similarly, patiquina plants have a wide variety of leaf colors and patternswhich makes them popular houseplants in North America-and these too

dona Maria generally grouped into morada and verde varieties. The dark plants

are among those used by sorcerers to inflict harm and are, therefore, most

powerful for healing and protection.

Dona Maria's antisorcery sweat bath contained the sorcery plants and catahua. Don Artidoro Aro Cardenas, a perfumero, a specialist in strong sweet

odors, says that, during a sweat bath with piiion Colorado, "you can actually see the phlegm, which is the bad magic, appear on the patient's skin as

it comes out of the body."" It is also possible to buy prepackaged sahumeria

bundles at the herb market in Belen in Iquitos.

Sometimes the expulsion of a pathogenic object during a sweat bath can

be quite dramatic. Dona Maria told me how, after she had studied with don

Roberto for about six months, she had treated a very sick woman, very thin

and pale, very debilitated. When dona Maria looked at the woman, she heard

a voice speak clearly in her ear: "This woman has an animal in her womb,

because of sorcery."

Now, a woman having an animal in her womb is not that unusual a diagnosis among mestizos. Pablo Amaringo tells of a woman who had the larva

of a boa implanted in her womb.22 Anthropologist Jean-Pierre Chaumeil

kept a calendar of the healing activity of Yagua shaman Jose Murayari for two

months, during which time the shaman healed two cases of animals in the

womb, both involving mestizo women .23 Dona Maria asked the woman how

long she had been sick; three months, the woman replied. "We have to take

this animal out ofyour womb as soon as possible," Maria told her, "because it

comes from sorcery."

What the plant spirits reveal is not only a diagnosis but, perhaps even more

important, an etiology. In this case, the woman's husband had been having

an affair with another woman, had left his wife for his mistress, and wanted

nothing more to do with his wife or their children-not an uncommon story,

even outside the Amazon. Still, in this case the mistress was using sorcery to

get rid of her rival. What the woman needed, the spirits told Maria, speaking

clearly in her ear, was an arcana, protection, from the sorcery of her husband's

mistress, and they told her what plants she should use to heal the woman and

what icaros she should sing. So Maria prepared a sahumeria, sweat bath, for

the woman, containing green and purple patiquina to fight the sorcery, and

other powerful plants to drive out the animal-catahua, a laxative; guaba, a

diuretic; aji, hot chili pepper; and the commercial disinfectant Creolina.

While the plants and water came to a boil, dona Maria prayed, and she

blew tobacco smoke into the woman, for protection, through the crown of her

head. She had the woman strip, except for a skirt around her waist, and squat

over the steam, with her legs open as if having a baby, just for a few minutes,

because the woman was so weak. Dona Maria began to sing an icaro, and the

sorcery left the woman's womb through her vagina, like a cohete, a rocketwhoosh! pung! said dona Maria, illustrating. The sorcery looked like a white

rabbit-a flash of something like cotton and then a gush of blood. "What?

What?" the woman cried out, and then they began to pray together, thanking

God for the healing, while blood rushed from the woman's vagina.

Dona Maria blew more tobacco smoke into the woman's body, sealed her

hands and forehead with drops of camalonga, and made the woman a hot drink of oregano and arnica, to seal her womb. Six days later the woman returned; although the woman had no money, dona Maria continued to treat

her. "Don't think bad thoughts about your husband and his girlfriend," Maria

told the woman. "They will get paid back for what they did." And Maria allowed the woman to pay her with her prayers. A year and a half later, the woman came to Maria with some money, but Maria refused to accept it, telling the

woman to use the money to take care of her children.

POULTICES

Among dona Maria's plant healing practices was the application of poultices;

the word she used was patarashca, which is also the word used for a serving

of fish that has been wrapped in one of the large leaves of the bijao palm and

barbecued on a grill.14 Dona Maria's patarashca generally consisted of the

chopped up leaves or stems of plantas brujas, sorcerer plants, wrapped in a

leaf; the patient puts the poultice on the place where the pathogenic object

is located, leaves it on overnight, and then burns it in a fire the next day. This

weakens the sorcery. The used poultice is not to be thrown away; it has pulled

out the sorcery and is now dangerous to handle. Among the plants dona Maria

uses in her poultices are mapacho, patiquina, toe, catahua, and aji.

Poultices are also used for the healing of snakebite. Mestizos and indigenous peoples in the Upper Amazon use a wide variety of plants for this purpose: ethnobotanists James Duke and Rodolfo Vasquez list twelve genera used

to treat snakebite; Richard Evans Schultes and Robert Raffauf list twentynine. Shamans all have their own songs to drive out venom and heal snakebite, usually called, generically, icaro de vi'bora, pit viper song. Don Roberto

has his own snakebite icaros; he applies a patarashca made of a banana leaf,

wrapped around the site of envenomation, and filled with the finely chopped

tuber of jergon sacha, changed every few hours. He also uses ishanga blanca,

white nettle, and cocona, as well as chewed leaves of mapacho applied directly

to the wound. The patient may be given a cold-water infusion of jergon sacha

to drink or cocona fruit boiled with sugar.

DONA MARIA'S LOVE MEDICINE

Dona Maria was known particularly for her pusangueria, love medicine, her

ability to make pusangas, love spells and potions. Pusangueria is widely

distributed in the Upper Amazon. A love potion is called pusdgki among the

Aguaruna, pusanga among the Campa, and posanga among the Machiguenga;25 a Machiguenga song says, in part, "My brother is going to smear her with a

posanga, and she is going to cry, my sister-in-law."" In Guyana and the Venezuelan Amazon, plant remedies called pusanas are used to gain sympathy or

love or to gain success in hunting or fishing.27 The Baniwa of Brazil use the

term pusanga to refer to a charm made from a thin, crawling vine called munutchi that produces a powerful perfume. Girls use the leaf of this vine to cause

boys to have terrible headaches .21

Snakebite

There are two families of venomous snakes in the Upper Amazon-the Crotalidae or pit vipers and the Elapidae or coral snakes. The Crotalidae are called pit

vipers because they have a pit or depression between the eye and the nostril on

each side of the head, which functions as an extremely sensitive infrared heatdetecting organ. In the United States, there are three genera of the Crotalidae

family-the copperhead, the cottonmouth or water moccasin, and fifteen species of rattlesnake.,

In the Amazon, the medically important coral snakes consist of fifty-three

species in the genus Micruris. Like the northern species, they have various

combinations of black and brightly colored rings. They are secretive and rarely

encountered; envenomation by these snakes appears to be rare. In the whole

of Brazil, only 0.65 percent of all snakebites reported from 2001 to 2004 were

attributed to coral snakes, and, in those 486 cases, there were no fatalities .3

The snakes of most medical concern are therefore the thirty-one species

of pit viper somewhat indiscriminately referred to by the name fer-de-lance or

lance head, all in the genus Bothrops and all very similar looking, with long bodies and large triangular heads. The lance heads live in the lowland jungle and

average four to six feet in length, although they may grow as long as eight feet.

They are generally tan with dark brown diamond-like markings along their sides

and are very well camouflaged. Amazonian pit vipers-as opposed to the colorful coral snakes-have clearly chosen crypsis over warning; it is easy to pass

very close to a fer-de-lance without noticing it.4 Species of Bothrops account for

9o percent of the snakebites in South America .5

Mestizos in the Upper Amazon generally refer to the various Bothrops species as vibora, the usual Spanish term for a pit viper, or as jergon. The Spanish

term cascabe!, rattler, usually refers to the genus Crota(us, which is not found

in neotropical environments but, rather, in dry habitats such as the savannas in

Guyana.6 In the Upper Amazon, the term cascabe( refers instead to juveniles of

the genus Bothrops, probably because the young have yellow tails?

The Amazonian bushmaster or Lachesis muta-the Latin name means silent

fate-is the largest pit viper in the world, reaching lengths up to twelve feet. Usually called by the Quechua term shushupi, the bushmaster is found in the lowland rain forest throughout the Amazon. It is generally a coppery tan with dark

brown diamond-shaped marks on its back, rather than on its side. It is active at

twilight and night and coils up in the buttresses of large trees or under roots and

logs. After having fed, a bushmaster will remain in place until it has digested its

prey, a period of two to four weeks.

Because of its length, a bushmaster can strike over a long distance; because

of its large fangs, it can deliver a large dose of venom-probably the largest

venom dose of any pit viper. However, bushmasters are very reclusive and therefore rarely encountered; many experienced tropical herpetologists have yet to

see their first wild specimen. As a result, few envenomations actually occur, although the fatality rate is reportedly high .8 I have been unable to find information about the age, physical condition, or treatment of reported fatalities.

Pit viper venom is a complex mixture of enzymes, which varies from species to

species and which is designed to immobilize, kill, and digest the snake's prey.9

The venom works by destroying tissue, and is capable of causing significant, sometimes disfiguring local tissue damage; but deaths-at least in the United

States, where records are available-are very rare and limited almost entirely to

children and the elderly.

Indeed, many pit viper strikes are dry and inject no venom, even when there

are fang marks; and the amount of venom discharged can vary from little or none

to almost the entire contents of the glands. Additionally, Crotalids can differ significantly in the toxicity of their venom, even within a single litter. With that said,

pit viper envenomation can be excruciatingly painful-one expert has said that

on a pain scale of i to io, rattlesnake bites are an ii-and the discomfort can

last for several days. The envenomated extremity can also become frighteningly

ugly, leading to panic in both the patient and the caregiver. Greater or smaller

areas of the extremity can turn blue or black, swell alarmingly, and develop large

blood blisters. It is altogether an unpleasant experience.