Sir Francis Walsingham

Read Sir Francis Walsingham Online

Authors: Derek Wilson

FRANCIS

WALSINGHAM

Also by Derek Wilson

Out of The Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007)

Hans Holbein: Portrait of an Unknown Man (2006)

Charlemagne: The Great Adventure (2005)

Uncrowned Kings of England: The Black Legend of the Dudleys (2005)

All The King’s Women: Love, Sex and Politics in the Reign of Charles II (2003)

A Brief History of the Circumnavigators (2003)

In The Lion’s Court: Power, Ambition and Sudden Death in the Reign of Henry VIII (2002)

The King and the Gentleman: Charles Stuart and Oliver Cromwell 1599–1649 (2000)

The World Encompassed: Drake’s Great Voyage 1577–1580 (2000)

Dark and Light: The Guinness Story (1998)

The Tower of London: A Thousand Years (1998)

Sweet Robin: Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (1997)

FRANCIS

WALSINGHAM

A Courtier in an Age of Terror

DEREK WILSON

CONSTABLE • LONDON

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

First published in the UK by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2007

Copyright © Derek Wilson 2007

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The right of Derek Wilson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in

Publication Data is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84529-138-9

eISBN: 978-1-47211-248-4

Printed and bound in the EU

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

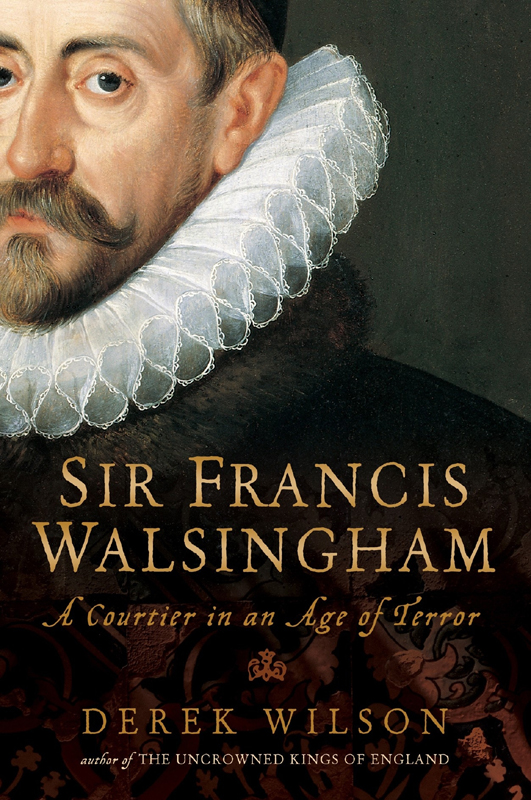

Jacket image: Sir Francis Walsingham (detail), John de Critz, National Portrait Gallery London; Design: Bob Eames

Introduction: August 1572, Death in Paris

1 Background and Beginnings, 1532–53

3 ‘The Malice of This Present Time’, 1558–69

4 ‘In Truth a Very Wise Person’, 1569–73

5 ‘To Govern that Noble Ship’, England, 1574–80

6 ‘God Open Her Majesty’s Eyes’: Foreign Affairs, 1578–80

7 ‘She Seemeth to be Very Earnestly Bent to Proceed’, 1581–4

8 ‘Be You All Stout and Resolute’, 1584–8

[2]

The Rainbow Portrait

by Isaac Oliver. Courtesy of the Marquess of Salisbury.

[6] Francis duc d’Anjou. Courtesy of the author.

[8] The assassination of William the Silent, 1584. Mary Evans Picture Library. 10157890.

[12] The Trial of Mary Queen of Scots. By permission of the British Library. Add. 48027.

State-sponsored terrorism, hit men paid to eliminate heads of state, mobs fired up by hate-shrieking ‘holy’ men, fanatics ready to espouse martyrdom in the hope of heavenly reward, asylum-seekers, internment camps, the clash of totally irreconcilable ideologies. The list is familiar to us but as well as highlighting some of the problems of twenty-first-century Britain, it also offers an accurate picture of England 1570–90. The middle years of Elizabeth I’s reign were years of crisis, uncertainty and anxiety. A cultural rift had sundered Europe. In the eyes of the major continental powers – France, Spain, the Empire and the Papacy – Henry VIII had committed the unforgivable sin of rending the seamless robe of medieval Christendom. What had emerged (certainly not what Henry had intended) was the first major independent Protestant state. For decades Catholic Europe, in disarray until the conclusion of the Council of Trent in 1563, was unable to address the problem of the dissident nation but thereafter the forces of Counter-Reformation returned to the offensive, determined to recover lost territories. Top of their agenda was the conquest of heretic England. In 1570, Pope Pius V solemnly declared Elizabeth deposed and her subjects released from their allegiance. France came under the domination of the fanatical leaders of the Guise family, who were determined to avenge the treatment of their kinswoman, Mary Queen of Scots. Philip II of Spain, no less committed to the Catholic cause, commanded the awesome power and wealth of a great trans-oceanic empire and spent years maturing what he referred to as the ‘Enterprise of England’.

If we fail to appreciate the tensions and fears of those years it is

because historical hindsight plays us false. We see the failure of Philip II’s Armada, the exploits of Francis Drake and other pioneer mariners, the Elizabethan renaissance of drama and verse and the era assumes a roseate hue. We are ready to take at face value the idealized image created by Elizabeth’s PR machine in the last decade of the reign: the legend of the Virgin Queen, Astraea, Gloriana.

Even supposedly serious historians colluded in the myth-making. William Camden, Elizabeth’s first biographer (his

History of the most renowned and victorious Princess Elizabeth, late Queen of England

first appeared in complete form in 1630), was quite open about the amount of veneration he mingled with objectivity.

That Licenciousness accompanied with Malignity and Backbiting, which is cloaked under the counterfeit Shew of Freedom, and is every-where entertained with a plausible Acceptance, I do from my Heart detest. Things manifest and evident I have not concealed; Things doubtfull I have interpreted favourably; Things secret and abstruse I have not pried into. ‘The hidden Meanings of Princes (saith that great Master of History [Polybius]) and what they secretly design to search out, it is unlawfull, it is doubtfull and dangerous: pursue not therefore the Search thereof.’

1

By the time the Civil War had intervened Elizabeth’s reign had assumed the glow of a golden age.

A Tudor! A Tudor! We’ve had Stuarts enough.

None ever ruled like Old Bess in the ruff.

2

So enthused Andrew Marvell in the 1670s.

His great-grandsire would not have endorsed such a eulogy. There was widespread discontent in late-Tudor England. Queen Elizabeth herself was in part responsible for the insecurity her people suffered. Despite urgent and repeated pleas from courtiers, councillors, parliamentarians and diplomats, she staunchly refused to fulfil what most people regarded as her first obligation: she would not provide the nation with an heir. She rejected the role of wife and mother and she declined to nominate a successor. Worse than that, she tolerated within the borders

of her realm a claimant to the crown in the person of Mary Stuart. For more than twenty years the ex-queen of Scotland lived as a virtual prisoner in England and became the focus for plots against the Tudor regime. Mary was the great hope of Catholics at home and abroad. If she could be placed on the throne by a native rising of people loyal to the old faith and aided by a foreign army, the clock could be turned back. England could be restored to that blissful age before Henry VIII had waged war on the pope – or so Catholic romantics fondly believed.

In English government circles perceptions of the international situation varied. Some believed in the existence of a Catholic conspiracy choreographed in Rome. Others remained convinced that the traditional policy of playing Habsburg and Valois interests off against each other was the best way of ensuring England’s security. Elizabeth, insofar as she can be credited with a consistent policy, adhered to the latter opinion. Francis Walsingham, her ‘foreign minister’, was convinced that the upholders of Protestant truth were locked in a cosmic struggle with the dark powers of papal Antichrist. The relationship between monarch and minister flavoured English politics throughout these crucial years. An understanding of Walsingham is, therefore, of first importance for an understanding of the dynamic of Elizabethan politics.

Francis Walsingham is a man about whom we know too little and too much. Copious official correspondence survives in the State papers and other deposits but these only relate to the last eighteen years of his life when he was ambassador to France and principal secretary of state. They tell us little about the forty years leading up to his achievement of high office, nor of his private life. Conyers Read’s monumental three-volume biography, written over eighty years ago, helps us very little in this regard, as its title suggests:

Mr Secretary Walsingham and the Policy of Queen Elizabeth.

In recent years Walsingham’s activities as head of the Elizabethan ‘secret service’ (a somewhat anachronistic expression) have fascinated several writers but his role as ‘spymaster’ covered an even shorter span of time (c.1580–90).

There was, of course, much more to the man that that. He was, for example, an enthusiastic backer of overseas exploration and merchant venturing. He was a cultured scholar so generous with his patronage that Edmund Spenser called him ‘the great Maecenas of this age’. But

his most powerful motivation came from his religion – that Protestantism that he had absorbed in family and Edwardian court circles and which further developed in his years of exile during Mary Tudor’s reign. Some biographers, disinclined to explore Walsingham’s beliefs or considering the evidence too scanty, have been content to apply to him the catch-all name ‘Puritan’. The term does him a disservice, suggesting as it does to modern minds a joyless, bigoted sobersides. Add to that his role as Elizabeth’s spymaster and the identification of Walsingham is complete as a sinister, narrow-minded, Machiavellian power behind the throne.

If, as I have suggested, the war on terror creates similarities between Elizabeth’s England and our own, there remains, of course, one fundamental difference between the two ages. Religion was central to all aspects of national and international life four and a half centuries ago. Political debate was shot through with it. Walsingham and the queen were both conviction politicians. Both believed that the security of the nation lay in making right religious choices. They simply could not agree what those choices should be. To Walsingham it was axiomatic that England should stand shoulder-to-shoulder with its persecuted brethren in France and the Netherlands and oppose the insidious spread of Catholicism with a programme of sound Protestant preaching and teaching. He was supported in this view by a sizeable portion of the political nation. Elizabeth was hesitant about encouraging foreign nationals to rebel against their divinely appointed rulers and was highly nervous of religious radicalism in all its forms. Her understanding of national stability was of all her subjects supporting

her

church, the Church of England, neither Catholic nor Puritan.