Smuggler Nation (33 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Most of this smuggling was about evading tariffs, whether on the part of tourists or professional illicit traders. But as we’ll see in the next chapter, smuggling during this time period also increasingly involved evading prohibitions. And unlike tariffs, the goal of prohibitions was to eradicate rather than tax and regulate. Prohibitions were not about commercial protectionism but moral protection and condemnation. Smuggling therefore became deeply entangled in the politics of sin, deviance, and vice in a rapidly changing American society.

11

Sex, Smugglers, and Purity Crusaders

THE POLICING OF SMUGGLING

in the post–Civil War era was first and foremost about revenue collecting, but it was also about purity crusading. Congress increasingly used its powers of regulating commerce to also suppress vice—providing another mechanism for enhanced policing powers. This began in midcentury with a federal prohibition on importing obscene material and then sharply escalated in the 1870s by extending the definition of obscenity to include contraceptives. Among other things, the import ban ironically helped protect and stimulate America’s nascent underground pornography business, while the expanded antiobscenity laws created a lucrative trade in contraband condoms.

The flourishing illicit trade in obscene pictures, publications, and devices fueled a decades-long moral crusade, with much of the enforcement outsourced to newly deputized antivice groups. But it was the alarm over sex trafficking—the so-called white slave trade—that sparked a full-blown moral panic. The nature and magnitude of this illicit sex trade in the first years of the new century turned out to be wildly exaggerated, in no small part due to hyped-up media accounts and national anxieties about rapid urbanization and an unprecedented influx of immigrants; yet it left a lasting legacy of more expansive federal anticrime laws and policing bureaucracies.

Smut Smuggling

Beginning with the Tariff of 1842, federal law banned the importation of “indecent and obscene” pictures; in 1857 obscene books were added to the list of prohibited items. Customs was empowered to seize these materials, adding more work for inspectors otherwise preoccupied with dutiable commerce. And as was the case with tariff enforcement, New York was also center stage in the effort to ban obscene materials. The first known case of enforcing the ban at the New York port involved the seizure of nine German snuffboxes containing indecent pictures.

1

But an ironic unintended consequence of attempting to eradicate smuggled smut was pornography protectionism—which jump-started a domestic porn industry.

2

Advances in printing technology enabled import substitution by making it possible to more rapidly and cheaply copy illicitly imported printed material. It was no longer necessary to smuggle in bulk quantities of foreign prints; a single smuggled copy would suffice. In the case of smuggled erotic literature, English publications were preferred since no translation was necessary.

3

It was standard practice for New York publishers to steal and copy English texts of all kinds, including illicit texts.

The trade in erotic photographs and other images, in contrast, faced no language barriers. Nude photographs were illicitly imported from the Netherlands and especially France. “Once smuggled into the United States,” historian Wayne Fuller notes, “they were reproduced again and again in small photography shops across the country.”

4

The invention and spread of photography made it possible to produce stunningly lifelike sexual images as never before, and their portability and low expense made them widely accessible. France had an especially notorious reputation as the world’s leading source of erotic photographs and began to inundate the U.S. market starting in the 1860s.

5

Further technological advances in cameras and photography equipment in the late nineteenth century made such photographs even cheaper and more available.

Meanwhile, an increasingly fast, affordable, and efficient U.S. mail service—made possible by the nation’s expanding railroad network—provided the ideal advertising and distribution mechanism for pornography peddlers.

6

And nowhere was this more evident than in mail deliveries to army camps during the Civil War, where Union soldiers

routinely received enticing flyers and catalogs from New York–based sellers detailing their sexually arousing offerings.

7

Erotic photographs were particularly easy to distribute via the mail. Using its powers to regulate trade, Congress responded by outlawing the mailing of any “publication of a vulgar and indecent character …” Violators could be fined up to $500 or imprisoned for up to one year.

8

Since mail was both foreign and domestic—and could include both obscene material and dutiable items—the missions of Customs and the Post Office increasingly overlapped. This created jurisdictional tension and competition but gave way to growing cooperation by the end of the nineteenth century.

9

The campaign against the trade in obscene materials really took off in March 1873 when Congress passed the Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use. The new law (which extended, expanded, and strengthened earlier bans) came to be known as the Comstock Act, named after the zealous antivice crusader Anthony Comstock. He made vice hunting his lifelong obsession, not only aggressively lobbying for a more expansive antiobscenity law but taking on the job of enforcing it as well. For the next four decades, no other person in America became more closely associated with stamping out the illicit trade in obscene materials, so much so that a new word, “Comstockery,” was coined.

10

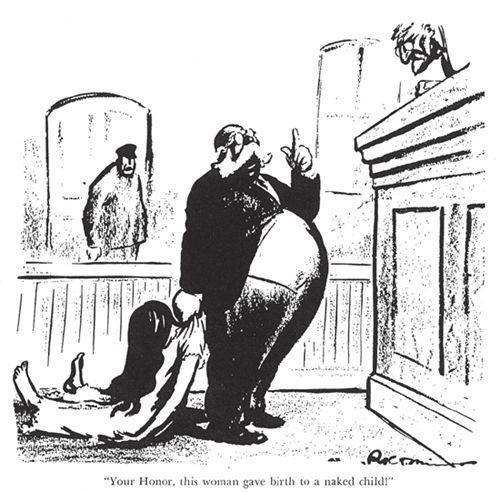

Although he was ridiculed in cartoons as fanatically prudish, his crusade was also cheered on in Victorian America and bankrolled by prominent wealthy New Yorkers.

Nassau Street in lower Manhattan was not only the hub of the pornography publishing business but also the headquarters for Comstock’s campaign to eradicate it. Comstock was the secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, backed by the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and influential donors. Empowered by federal law and appointed as a special agent of the U.S. Mail, Comstock and his collaborators kept long, detailed lists of arrests, convictions, and seizures as a running tally of their successes.

11

Many arrests were made through elaborate “buy and bust” sting operations, with Comstock often posing as a would-be customer. Penalties for violators included one to ten years in prison and fines up to $5,000. By the time he died in 1915, he had made 3,873 arrests (with more than 2,900 convictions) for Comstock law violations.

12

Painting the obscenity threat as largely of

foreign origin, he disproportionately targeted immigrants. Highlighting statistics on the high number of nonnative citizens arrested, Comstock reported, “It will be seen at a glance that we owe much of this demoralization to the importation of criminals from other lands.”

13

Figure 11.1 “Your Honor, this woman gave birth to a naked child!” One of many political cartoons that ridiculed Anthony Comstock and his antivice crusade.

The Masses

, 1915 (Granger Collection).

In addition to arrest numbers, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice also meticulously compiled seizure statistics. The society’s 1900 annual report summed up its work to date: “Books and Sheet Stock seized and destroyed—78,608 lbs; Obscene Pictures and Photos [seized and destroyed]—877,412; Negative Plates for making Obscene Photos [seized and destroyed]—8,495; Engraved Steel and Copper Plates [seized and destroyed]—425; Stereotype Plates for Printing Books,

etc.

[seized and destroyed]—28,050 lbs; Indecent Playing Cards destroyed—6,436; Circulars, Catalogues, Songs, Poems,

etc.

[destroyed]—1,672,050.”

14

By the end of Comstock’s four-decade

mission to suppress smut, he had confiscated fifty tons of books and four million pictures and made some four thousand arrests. Comstock even pointed to more than fifteen suicides as an indicator of his success.

15

Figure 11.2 Seal of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, founded in 1873. On the left, an illicit purveyor of obscene materials is taken into a cell; on the right, seized obscene materials are burned (Granger Collection).

One prominent suicide case was the Irish immigrant William Haines, who made a fortune selling hundreds of thousands of copies of obscene books from the 1840s to the early 1870s. He played a pioneering role in the emergence of the U.S. pornography trade, entering it the same year as the first federal ban on imports and becoming “the nation’s largest and most notorious publisher of erotic print.”

16

The night before he committed suicide he received a message: “Get out of the way. Comstock is after you. Damn fool won’t look at money.”

17

But far from eradicating the illicit trade, Comstock’s crusade instead transformed it, pushing it more into the shadows and out of sight. The

trade was also increasingly pushed out of New York, unintentionally spreading it to other towns and cities across the country.

18

Pornographers creatively adjusted to the new prohibitionist climate, using aliases and false addresses and increasing their bribes and payoffs to the authorities;

some even posed as religious publishers.

19

Pornography traders also shifted to more portable and lightweight products—away from bulky books and toward more concealable items such as photographs and playing cards.

20

Similarly, as it became riskier to use the U.S. mail system, illicit traders increasingly turned to private express companies to reach their customers.

21

Comstock’s targeting of the most established publishers also created openings for new market entrants attracted by the unusually high profits of the trade (with expected profit margins as high as 500 percent).

22

The illicit import side of the trade also survived Comstock’s crackdown. As domestic publishing became a much riskier business, a high-end niche import trade also flourished in the late nineteenth century aimed at wealthy clientele willing to pay a premium for “luxury erotica” smuggled in from Europe.

23