Smuggler Nation (37 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

The federal government had no stand-alone immigration control apparatus when the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, so the job of implementing it was handed to customs agents within the Treasury Department. It was an awkward fit, especially at first. Customs was created to oversee the entry of goods, but it was now suddenly expected to also monitor and police the entry of people. Customs, in turn, sometimes treated people as if they were actually goods, often calling Chinese “contraband”; on one inspection list, “Chinese laborers” was even entered as a line item between “castor oil” and “cauliflower in salt.”

24

A Bureau of Immigration was created in 1891 (later moved into the newly established Department of Commerce and Labor in 1903), but Customs remained in charge of enforcing the exclusion law until the turn of the century. A “Chinese Bureau” within Customs was set up in San Francisco in the mid-1890s, headed by the collector of customs and staffed by “Chinese inspectors.”

Opening the Northern Back Door

As front-door entry through San Francisco and other seaports became more regulated in the late nineteenth century, more and more Chinese immigrants turned to entry though the back door: America’s vast and minimally policed northern and southern land borders.

25

Canada became the favored transit country for smuggling Chinese immigrants into the United States in the late 1880s and 1890s.

26

Chinese arrivals in Canada increased sharply during this period. Regular steamship service connected China and Canada, and Chinese immigrants had no problem entering Canada so long as they paid a head tax. The Canadian Pacific Steamship Company and Canadian officials generally had a lax attitude, knowing full well that most of the Chinese were just passing through. As one Canadian official bluntly told an American journalist in 1891, “They come here to enter your country, you can’t stop it, and

we don’t care.”

27

With Canada collecting a head tax on every Chinese entry, the Canadian government was even making money from it. One Canadian official joked, “We get the cash and you get the Chinamen.”

28

From 1887 to 1891 alone, Canada collected $95,500 in head taxes.

29

In 1885 the head tax was $50 on Chinese laborers, and this was raised to $100 in 1900 and to $500 in 1903.

30

U.S. officials bitterly complained that Canada’s virtually open door policy “practically nullified … the effective work done by the border officers.”

31

In 1902, U.S. immigrant inspector Robert Watchorn reported, “Much that appears menacing to us is regarded with comparative indifference by the Canadian government.” As he described it, “those which Canada receives but fails to hold … come unhindered into the United States.”

32

The westernmost stretch of the Canadian border was initially the favored illicit entry point. An unintended consequence of the Exclusion Act was to create a law enforcement problem far from San Francisco and the nation’s capital. As Special Agent Herbert Beecher wrote in 1887, the U.S. exclusion law was “created without practical knowledge of what was required of it. A law created apparently more for California, with no thought or knowledge of its workings in Washington Territory, situated as we are, so closely to British Columbia, commanding as it does such natural advantages of evasion of the Restriction Act.”

33

Customs agents long preoccupied with the smuggling of goods through the ports of entry now had to also deal with the smuggling of people through the vast areas between the ports of entry. In the 1890s, the cost of hiring a smuggler to cross the Northwest border was anywhere between twenty-three and sixty dollars.

34

The waterways of the Puget Sound were especially difficult to police and therefore conducive to smuggling Chinese migrants in by boat at night. Local Chinese served as agents and intermediaries for those being smuggled, but white men reportedly handled the actual transportation given that they enjoyed greater freedom of movement across the border.

35

Smuggling operations involved not only close business collaborations between Chinese and white merchants but sometimes also paying off U.S. border agents.

36

Smuggling gradually shifted eastward along the northern border (greatly facilitated by the establishment of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885) in response to intensified U.S. enforcement in the west. Eastern

states such as New York and Vermont consequently also turned into entry points for smuggled Chinese.

37

These geographical shifts in smuggling in turn stimulated a geographic expansion of immigration law enforcement.

38

The growth of human smuggling in defiance of the exclusion laws also fueled alarmist political rhetoric in Washington. In the words of one journalist covering the issue, this included “amazing utterances in Congress, in which, among others, one speaker had likened the influx of contraband Chinese to nothing less than the swarming of the Huns in early European history.”

39

The influx of smuggled Chinese across the northern border was ultimately curbed not by tighter U.S. border controls but by changes in Canadian policy that were partly induced by U.S. pressure. This included imposing a prohibitively expensive head tax,

40

turning away Chinese who had previously been denied entry to the United States, allowing U.S. inspectors to enforce U.S. immigration laws on Canadian-bound steamships and at Canadian ports of entry, and agreements with Canadian steamship and railroad companies to pre-screen passengers and curtail the transport of U.S.-bound migrants.

41

And in 1923 Canada imposed its own Exclusion Act (admitting only merchants and students), dramatically reducing the use of Canada as a conduit for smuggling Chinese into the United States.

42

Opening the Southern Back Door

As the back door through Canada began to close, the back door through Mexico started to swing wide open in the first decade of the twentieth century. Rather than ending Chinese smuggling, U.S. pressure on Canada simply redirected it to Mexico—and Mexico was far less inclined to cooperate with the United States, given the still-festering wounds from having lost so much of its territory after the Mexican-American War. U.S. State Department efforts to negotiate agreements with the Porfirio Díaz regime to curb Chinese entries went nowhere.

43

The U.S.-Mexico border, long a gateway for smuggling goods, was now also becoming a gateway for smuggling people. As was the case in Canada, new steamship, railway, and road networks greatly aided migrant smuggling through Mexico. But unlike in Canada, Mexican transport companies showed little willingness to cooperate with the

United States. An agent for one steamship company reportedly told U.S. authorities that his next scheduled ship was expected to carry some three hundred Chinese passengers to the northern Mexican port of Guaymas. “For all I know they may smuggle themselves into the United States and if they do I do not give a d-n, for I am doing a legitimate business.”

44

Guaymas was connected by railway to the border town of Nogales.

The development of new transportation networks linking the United States and Mexico was hailed as a boon for cross-border commerce. As President Benjamin Harrison commented in his annual message to Congress at the end of 1890: “The intercourse of the two countries, by rail, already great, is making constant growth. The established lines and those recently projected add to the intimacy of traffic and open new channels of access to fresh areas of supply and demand.”

45

Left unstated was that these very same channels also facilitated illicit traffic.

46

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce signed by China and Mexico in 1899, and the establishment of direct steamship travel between Hong Kong and Mexico in 1902, opened the door for a surge in Chinese migration to Mexico. And this, in turn, provided a convenient stepping-stone for clandestine migration to the United States.

47

In 1900 there were just a few thousand Chinese in Mexico, but less than a decade later nearly 60,000 Chinese migrants had departed to Mexico. Some stayed, but the United States was a far more attractive destination.

48

A banker in Guaymas, the Mexican port in the border state of Sonora, told U.S. Immigration Inspector Marcus Braun in 1906 that about twenty thousand Chinese had come to the state in recent years, but fewer than four thousand remained.

49

In his investigations, Braun witnessed Chinese arriving in Mexico and reported that “On their arrival in Mexico, I found them to be provided with United States money, not Mexican coins; they had in their possession Chinese-English dictionaries; I found them in possession of Chinese-American newspapers and of American railroad maps.”

50

In 1907, a U.S. government investigator observed that between twenty and fifty Chinese arrived daily in the Mexican border town of Juarez by train, but that the Chinese community in the town never grew. As he put it, “Chinamen coming to Ciudad Juarez either vanish into thin air or cross the border line.”

51

Foreshadowing future developments,

a January 1904 editorial in the El Paso

Herald-Post

warned that “If this Chinese immigration to Mexico continues it will be necessary to run a barb wire fence along our side of the Rio Grande.”

52

The El Paso immigration inspector stated in his 1905 annual report that nearly two-thirds of the Chinese arriving in Juarez are smuggled into the country in the vicinity of El Paso, and that migrant smuggling is the sole business of “perhaps one-third of the Chinese population of El Paso.”

53

With Mexico becoming the most popular back door to the United States, some smugglers relocated their operations from the U.S.-Canada border to the U.S.-Mexico border. One smuggler who made this move, Curley Roberts, reported to a potential partner: “I have just brought seven yellow boys over and got $225 for that so you can see I am doing very well here.”

54

Some historians note that border smuggling operations involved cross-racial business collaborations, with white male smugglers often working with Chinese organizers and Mexicans serving as local border guides.

55

A 1906 law enforcement report on Chinese smuggling noted, “All through northern Mexico, along the lines of the railroad, are located so-called boarding houses and restaurants, which

are the rendezvous of the Chinese and their smugglers, and the small towns and villages throughout this section are filled with Chinese coolies, whose only occupation seems to be lying in wait until arrangement can be perfected for carrying them across the border.”

56

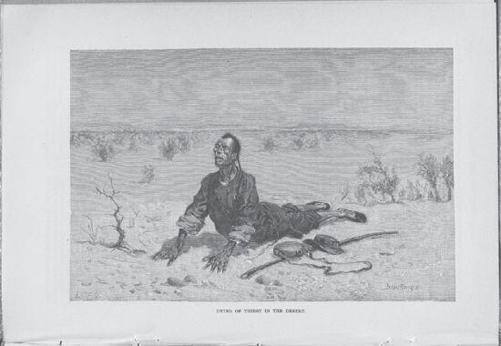

Figure 12.3 “Dying of Thirst in the Desert.” Drawing depicts the serious risks and dangers for those attempting to cross the border in remote areas.

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

, March 1891 (John Hay Library, Brown University).

As U.S. authorities tightened enforcement at urban entry points along the Mexico-California border, smugglers shifted to more remote parts of the border further east in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

57

And following the earlier pattern on the U.S.-Canada border, this provided a rationale for the deployment of more agents to these border areas. In addition to hiring more port inspectors, a force of mounted inspectors was set up to patrol the borderline by horseback. As smugglers in later years turned to new technologies such as automobiles, officials also pushed for the use of the same technologies for border control.

58

With the tightening of border controls, smugglers sometimes opted to simply buy off rather than try to bypass U.S. authorities in their efforts to move their human cargo across the line. This was the case in Nogales, Arizona, where border inspectors, including the collector of customs, reportedly charged smugglers between $50 and $200 per head until their arrest by special agents of the Treasury Department and Secret Service operatives in August 1901. Covering the case, the

Washington Post

reported that “with two or three exceptions, the whole customs and immigration administration at Nogales are involved” in the smuggling scheme.

59