Somebody's Heart Is Burning (19 page)

“Pencil, pencil!” they called, a chorus of high, plaintive voices.

“Paper!” called a single voice. It sounded like pay-pah. They all took up the cry.

“Pay-pah! Pay-pah!”

“Oh, God,” I said to Katie. “What have we done?” A cliché sprang to my mind, something about the road to hell.

“Look,” said Katie. “Some children are going through the rubbish.”

I looked. At the side of the house, a cluster of children was ripping apart the plastic bag that held our trash, grabbing frantically at the contents. Bits of paper were scattered about the ground. Baba and a slightly older boy had their hands on an empty insect repellent bottle and were pulling back and forth, shouting furiously at each other. Little Essi was on Baba’s back, and Kwesi sat on the ground, screaming. Then the boy Baba was struggling with saw a package of stale cookies and immediately let go of the bottle. He grabbed the package and ran, stuffing the cookies into his mouth. Several other children were examining some used sanitary pads.

Baba began rubbing the insect repellent onto her thin arms.

“Tell her that’s poisonous,” I said to Billy. “She shouldn’t get it near her eyes or mouth.”

Billy strode over and grabbed the bottle from Baba, speaking sharply to her.

“If you use this and something bites you it will have no effect on you?” he called to me.

“It’s supposed to keep bugs away,” I told him distractedly. “They don’t like the smell.”

He chuckled and shook his head, then rubbed a few drops onto his own knuckles.

“Goodbye, sistahs,” he said absently, examining the plastic bottle. “Come again.”

The children followed us down the hill to the dusty road. We threw our backpacks on the ground and sat on them while we waited for a taxi to arrive. We didn’t look at the children, or at each other. Their voices filled the air around us,

pencil, pencil,

paper, paper.

They were still keening half an hour later as we climbed into the taxi and rode out of sight.

11

Another American

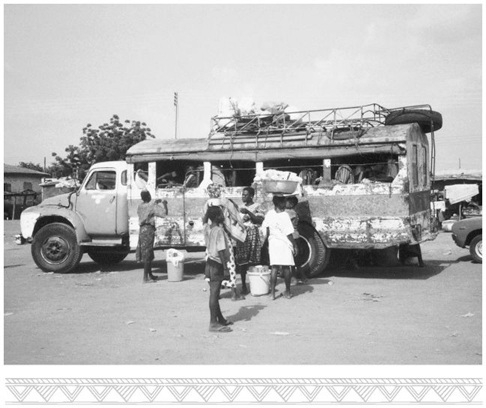

On each bus or

tro-tro,

there are two sta f people: the driver and his

assistant. The assistant acts as a barker, calling out the destination and

enticing passersby, then shepherding the passengers onto the vehicle,

collecting the money, and overseeing the baggage. These assistants are

efficiency incarnate. Without a moment’s hesitation, they assess your

baggage and proclaim a charge: 200 cedis, 400, 1,000. With a flick of the

finger they tell you it’s your turn to pay up. A glance at the driver says,

This van is full, let’s go; another glance says, Slow down, there’s a man

running to catch up. They glide on and off the moving

tro-tro,

collecting passengers, paying tolls, making room.

I admire these fluid men: the grace of their ascents and descents, their

willingness to hang halfway out the door to accommodate more passengers. In my imagination, they are not skinny, overworked youth in dangerous dead-end jobs, but high priests of the roadways, following a sacred

calling passed down from father to son. They’ve caught the rhythm of the tro-tro,

and like any good artist, they make it look easy, like laughter,

like rain.

The day began with a sharp 5 A.M. rap on the door. Katie moaned from beneath her mosquito net. I stumbled out of my sleeping bag and through the door, clutching my gut. When I returned from the latrine, she was still lying there.

“Rise and shine, girlfriend,” I said. “Bus leaves at five-thirty and look at this room.”

As a final detour before returning to Accra, we’d spent a single night in the lodge at the Mole Game Reserve. There we’d exercised our unique talent for demolishing a space. Clothing, books, water bottles, and packets of malaria pills were scattered haphazardly across the cement floor. Our backpacks sat in opposite corners of the spacious room, spread-eagled and overflowing. The room looked as if a giant had picked it up and shaken it to make it snow.

Katie moaned again. “My stomach feels squidgy.”

“You too? What’d we have last night?”

“Groundnut soup with rice balls.” She stared at me flatly. “Seemed fine at the time.”

“Should we stay another day?” We’d planned to arrive in Accra tonight, a journey that would require a host of bus and truck connections.

“Nooooo,” she said, heaving herself into a sitting position. “Let’s take this bus, anyway. Later we can decide if we want to keep going. This place is too dear.”

Bleary-eyed, we picked our way toward the bus in the predawn darkness. We’d spent the previous day tromping through the dense undergrowth of the Game Reserve with a guide, looking for animals. It had rained a lot over the past week, and we inhaled the restorative scent of clean, wet earth. Our guide, Kwame, was a polite, self-effacing young man barely out of his teens. He had a round, dimpled face, large soft eyes, and a voice so quiet you had to lean close to hear his words. He seemed to feel personally responsible, both for the dearth of animal appearances and for the fact that an hour or so into our trek the sky saw fit to douse us with another downpour. Although we assured him that no one blamed him, he continued to apologize, disarming us with his dimpled grin. We withstood the rain as long as we could, then retreated to the lodge for tea, having seen exactly three long-legged antelope, two elephants (from so far away they look like rocks in my photos), and a plethora of colorful birds.

The bus out of Mole turned out to be one of the nicest buses I’d seen in Ghana. Its interior was shiny and clean, with cushioned vinyl seats. It was empty except for a few Ghanaians and another white woman sitting toward the back. Katie and I took separate seats and lay down to nap the trip away, roads permitting.

The bus began to roll silently, as though a handbrake had been released. Just as I began to wonder when they would fire the motor, I heard a man’s voice shouting from outside the bus. The driver braked sharply, nearly throwing me off the seat. The driver opened the door, and Kwame boarded the bus, dressed in his Game Reserve uniform. He whispered something to the driver, who simply shrugged.

“Hi there,” I said, smiling sleepily as Kwame walked past my seat. He nodded to me in a perfunctory, distracted way. Continuing to the back of the bus, he stopped at the second to last row, where the other white woman sat slumped in her seat.

“Miss,” he said softly.

She remained motionless. He lightly placed a hand on her shoulder, to rouse her.

“Miss,” he said again, slightly louder. Abruptly, she jumped back, knocking his hand away.

“Hey!” She let out a startled sound, somewhere between a shout and a snarl.

“I’m sorry to disturb you, miss,” Kwame said gently.

“Then don’t,” she said, turning toward the window. Her accent was distinctly American, hard and flat.

“I don’t wish to disturb you,” he began again, “but I’m afraid you have not yet paid for your last night’s room.”

“I paid for it,” she said, without looking at him. “Ask the guy at the desk.”

“It is he who requested that I speak to you, miss,” said Kwame.

“Why didn’t he come himself?”

“He is still bathing.”

“Well, he’s a goddamn liar. I already paid for my fucking room.”

Our small community of passengers, which had hitherto been too sleepy to take much of an interest in these goings-on, perked right up when it heard that. The five or six Ghanaian passengers scattered throughout the bus swiveled in their seats, sliding toward the aisle for a better view. The driver shifted uneasily. Even Katie, who’d seemed dead to the world, hoisted herself to a sitting position and shot me an anxious look.

Back in the U.S., I’d rarely dwelt on the fact that I was American. I might rail against the government and the emptiness of popular culture or ruminate with guilty gratitude on the freedoms and privileges I enjoyed, but I seldom reflected on the fact of my citizenship as a central part of who I was. Instead, I drew my identity from the things that made me other: Jewish, female, artist, etc. Traveling in Africa brought my Americanness acutely into focus. Everyone I met had such strong ideas about the U.S. that I found myself adjusting my descriptions to counter each individual’s perceptions. Since most Ghanaians imagined a promised land, I was quick to paint for them a troubled nation, rife with injustice. For the Europeans who believed all Americans were fervid imperialists, gung ho to impose our brand of corporate capitalism on the world, I hastened to explain that the American people aren’t the government—that there is, in fact, a vibrant counterculture within the U.S. that rejects our role as global bully.

With the exception of Nadhiri, I experienced an easy kinship with other American travelers. In addition to sharing a native language, Americans were friendly, gregarious in a way that European travelers often were not. My European friends found American mannerisms superficial, even phony. They mocked the cheery

Have-a-Nice-Day

attitude with vapid smiles and puppet-like bobbing of the head. I, on the other hand, found it reassuring. In my view, encounters that happened during travel were often brief and superficial. If I was going to have a superficial encounter anyway, I’d just as soon it be a friendly one.

But the sense of connection with American travelers went beyond that. I felt implicated by their behavior, even responsible for it. So when Katie whispered, “What’s going on?” on the bus that morning, I felt oddly defensive.

“How should I know?” I mouthed.

“I’m afraid you are mistaken, Miss,” Kwame said to the young woman, hovering above her seat. “The records show that you have not paid.”

At that, she launched into a furious stream of invective:

“I

paid 5,500 cedis to stay in this fucking pisspot shithole; I paid that

motherfucking cocksucker at the desk yesterday, but he didn’t write it

down in your shitass books . . .”

Kwame stood impassively as the foul torrent continued, toxic as an oil spill. My stomach turned over uneasily.

“Katie,” I whispered, “I feel sick,” but she didn’t hear me. She was transfixed. The entire population of the bus was watching the scene with the avid curiosity of accident-mongers at the site of a mangled truck.

It was impossible to tell what the young woman’s face looked like in repose. It was a mask of rage, her features scrunched and contorted, pale skin splotched with red, puffy eyes leaking tears. Her voice, too, was barely human, shrill as the call of a ravening bird. Watching her, I felt first numb, then horrified, then acutely, violently ashamed.

“You’re gonna have to drag me off this fucking

tro-tro

. . .”

Kwame flinched, barely perceptibly. The bus was the pride of the Game Reserve. For her to call it a

tro-tro

was a patent affront. Amid the sea of generic obscenities, the word jumped out, sharp and specific. The whole bus reacted subtly, as if drawing in its breath.

“That’s right, you cunt-lickers are gonna have to drag me off this

fucking thing . . .”

Kwame turned his head and made eye contact with the driver, who gave a slight shrug. Adjusting his round hat on his balding head, the driver began to rise, a grim expression on his face.

The young woman’s eyes darted sharply from one man to the other. Then the outburst stopped, midsentence, as abruptly as it had begun.

“All right, all right!” she shouted. She reached down beneath her seat and pulled out a small woven purse. Thrusting her hand into it, she extracted a wad of bills.

“One thousand, two thousand,” she counted in a taunting voice. When she reached 5,500 she threw the handful of bills at Kwame. A couple landed in his hands, while several others fluttered to the floor. Keeping his eyes on her, he crouched slowly to pick them up. She made a sudden motion, causing him to start slightly. She laughed harshly. Kwame silently recounted the money. Then he nodded, folded the bills neatly and put them in his pocket.

“Thank you. Safe journey,” he said. He walked down the aisle and off the bus. The doors swung closed, the engine purred gently to life, and the bus glided out through the trees into the graying dawn. Ten minutes later I was at the side of the road, expelling the contents of my stomach in a patch of coarse grass.

In the weeks to come, our story spread through the ranks of volunteers like a flu in a kindergarten. At each telling the American woman became more hideous and the Ghanaian man more saintly.

“He was the absolute picture of dignity,” Katie said. “He just let her rave.”

“I felt ashamed to be American,” I told a Danish friend. “Ashamed to be white. I wanted to cover my body, to hide.”

Soon the story joined the ranks of volunteer legend, forming a cautionary trilogy with the tales of the Swede who nearly drowned in a toilet pit and the Brit who visited a fetish priest and subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown, growing paranoid and delusional, hiding from the Africans, eating only prepackaged foods after inspecting the packaging for holes. These weren’t moralistic tales, exactly. They were more like ghost stories—nightmarish anecdotes traded for shock value. They inspired personal rituals of self-protection: wood-knocking, fingercrossing, whispered prayers.

“Please don’t let me fall into a toilet pit,”

I’d whispered over and over when I first arrived.

“If I get out of here without falling into a

toilet pit, I won’t kill bugs, I’ll call my parents regularly, I’ll never complain about anything ever again for the rest of my life.”

In much the same way, I tried to immunize myself against the American woman’s fate by telling her story in as distancing a manner as possible. Secretly, she terrified me. Her condition seemed contagious, something that could happen to you, as random and inexplicable as the Swede’s fall to earth. You could catch malaria. You could get a sunburn. An Ugly American could move into your body and inhabit it. You could be Ugly without knowing you were Ugly. You could be Ugly to everyone around you, all the while thinking you were Right.