Sons (8 page)

Authors: Evan Hunter

“Would you like some milk?” she asked me now.

“Another air-raid drill today,” I said, going to the refrigerator.

“I gathered,” she answered.

There was some leftover icebox cake on the second shelf, and I cut a small slice of it. Then I poured myself a glass of cold milk, and took everything over to the round kitchen table under the Tiffany lamp. We generally took breakfast with the fork (one of my mother’s expressions, translated from the English to mean a breakfast including some kind of meat, usually sausage), and since I didn’t get to school each day until nine o’clock, I wasn’t hungry enough to cat very much of the school lunch at noon. But neither did I dare eat anything substantial when I got home in the afternoon because dinner was at six-fifteen sharp and my mother was a stickler for eating everything put before you. So I usually just took the edge off my appetite with a little milk and maybe a chocolate pudding, or a few cookies, and then went into the living room to do my homework. We had a new Philco floor-model radio there, complete with push buttons, and as I worked I would listen first to “Terry and the Pirates” and “The Adventures of Jimmy Allen” in breathless succession on WENR, then a quick flick of the dial at five-thirty for “Jack Armstrong” on W67C, and then back to WENR for “Captain Midnight” at five forty-five. At six on the button. I’d hear my father’s key in the latch, and the front door would open, and he would call his customary greeting, “Hello, anybody home?”

At dinner that night, I decided to reopen the Air Force issue.

My father seemed to be in a very good mood. He was talking about a recent War Production Board memo that eulogized the paper industry and made the printed word sound as important to the war effort as bullets. I always listened in fascination when my father talked about paper. I could never visualize him doing anything but work of a physical nature; his lumberjack background seemed entirely believable to me. When he came home from work each evening wearing a gray fedora and a gray topcoat and a pinstriped business suit, I was always a little surprised that he wasn’t wearing boots and a mackinaw and a turtleneck sweater. He was a big man, still very strong at forty-three, with penetrating blue eyes and a nose I liked to consider patrician (since I had inherited it). The table in the paneled formal dining room was eight feet long without additional leaves, and whereas my father always sat at the head of it, my mother did not sit at the opposite end but instead took a chair on his right, closest to the kitchen. She refused to keep a bell on the table (“Never count the number a bell tolls, for it’ll bring you that many years of bad luck”) and would more often than not rise and go into the kitchen herself if the maid didn’t respond to her first gentle call. My sister Linda always sat on my father’s left, and I sat alongside her, which was not the happiest of arrangements, since she was left-handed and invariably sticking her elbow in my dish.

“Well,” I said, subtly I thought, “it looks as if Michael Mallory will be leaving for the Air Force soon.”

“And here I thought we were actually going to get through a meal without hearing Will’s enlistment pitch,” my father said.

“The wheel that docs the squeaking is the wheel that gets the grease,” my mother said. “Don’t you know that, Bert?”

“If I wait till my eighteenth birthday,” I said, unrattled, “and then get drafted, I’ll end up in the Infantry.”

“Let’s wait till your eighteenth birthday and find out, shall we?” my father said.

“Sure, I’ll send you letters from Italy. Written in the mud or something.”

“You spent six summers at camp without writing a single letter,” my father said. “I have no reason to believe you’ll be changing your habits when and if you get to Italy.”

“That wasn’t my point,” I said.

“Your father knows your point,” my mother said.

“I’ll be eighteen in June,” I said.

“We know when you’ll be eighteen.”

“Well, for crying out loud, do you

want

me to go into the Infantry?”

want

me to go into the Infantry?”

“I don’t want you to go

anywhere,”

my father said flatly.

anywhere,”

my father said flatly.

“Well, that’s fine, Pop, but Uncle Sam has other ideas, you know? Whether you realize it or not, there

happens

to be a war going on.”

happens

to be a war going on.”

“Living in the same house with you, it’d be difficult not to realize that,” my father said, and picked up his napkin, and wiped his mouth, and then looked me in the eye and said, “What’s your hurry, Will? You anxious to get killed?”

“I’m not in any hurry,” I said.

“You sound like you’re in one

hell

of a hurry, son.”

hell

of a hurry, son.”

My sister glanced up at him quickly; it was rare to hear my father using profanity, even a word as mild as “hell.”

“I’m only trying to protect myself,” I said.

“Yes, by rushing over there to fly an airplane.”

“Yes, which is a lot safer than...”

“No one’s safe in war,” my father said. “Get that out of your head.”

“Look,” I said, “can we talk reasonably for a minute? Can we just for a minute look at this thing reasonably?”

“I’m listening,” my father said.

“It’s reasonable to expect that I have to register when I’m eighteen, and it’s reasonable to expect I’ll be put in 1-A, and it’s reasonable to expect I’ll be drafted.”

“Yes, that’s reasonable. Unless the war ends before then.”

“Oh, come on, Pop, you can’t believe the war’s going to end before June!”

“It may end before you’re trained and sent overseas.”

“Okay, then you should be very happy to let me join the Air Force. It takes longer to train a fighter pilot than it docs an infantryman.”

My father was silent. I felt I had made a point.

“Isn’t that reasonable?” I asked.

“It’s only reasonable for my son to stay alive until he becomes a man,” my father said.

“You

stayed alive, didn’t you?” I said.

stayed alive, didn’t you?” I said.

“I was lucky,” he answered.

AprilI didn’t know what I was doing on a troopship in Brooklyn. I wanted to be with Nancy. Instead, I was sitting in the blacked-out hold of a British vessel, on the edge of a bunk which was the bottom one in a tier of four, waiting to sail for Brest. I couldn’t believe it. Nor could I even understand how I had got here.

My father was fond of saying that all of America’s troubles had started with the assassination, a premise I couldn’t very well argue, since I was only a year old when McKinley got shot. And even though the shock of the murder seemed to sift down through the next ten years or more, as if the idea of something so primitive happening in a nation as sophisticated as America took that long to get used to, it was never more than a historical event to me, vague and somehow unbelievable. I was, frankly, more moved when the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife got killed. Not shaken to the roots, mind you (I was fourteen, going on fifteen, too old to be carrying on like an idiot) but frightened and excited by everything that happened in the month that followed: Austria-Hungary declaring war on Servia; Russia moving 80,000 troops to the border; Germany declaring war on Russia; Germany declaring war on France; Germany invading Belgium; England declaring war on Germany; everybody declaring war on everybody else — except the United States.

We were neutral.

We were sane.

To me, in Eau Fraiche, Wisconsin, the war was something that erupted only in newspaper headlines — I didn’t know where Servia was, and I couldn’t even pronounce Sarajevo. England was the only country with which I felt any real sympathy, but that was because both my parents were of English stock; my father, in fact, had been born and raised in Liverpool. But even then, I think my own attitude about the war in those early days was a reflection of what the rest of America was thinking and feeling, or at least the rest of America as represented by the state of Wisconsin. It wasn’t our battle. We were determined to stay out of it. We had headaches enough of our own — all that mess down there in Mexico which we

still

hadn’t resolved, and people out of work everywhere you looked, and southern Negroes causing even bigger job problems by moving in batches to the north and the midwest — we didn’t need any war. And anyway, even though Germany’s march into Belgium had caused us to sympathize momentarily with the underdog, it was really pretty hard to believe that people related to gentle Karl Moenke, who ran a dry-goods store in Eau Fraiche, could be even remotely capable of sacking Louvain, and shooting priests and helpless women there. The war for us was fascinating but remote. We didn’t want involvement. We said we’d remain neutral, and that was our honest intention.

still

hadn’t resolved, and people out of work everywhere you looked, and southern Negroes causing even bigger job problems by moving in batches to the north and the midwest — we didn’t need any war. And anyway, even though Germany’s march into Belgium had caused us to sympathize momentarily with the underdog, it was really pretty hard to believe that people related to gentle Karl Moenke, who ran a dry-goods store in Eau Fraiche, could be even remotely capable of sacking Louvain, and shooting priests and helpless women there. The war for us was fascinating but remote. We didn’t want involvement. We said we’d remain neutral, and that was our honest intention.

And yet — there was something. There’s always something about war, a contagious excitement that leaps oceans.

I couldn’t look at the battle maps printed in the Eau Fraiche

Record

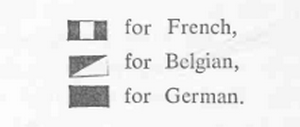

without visualizing gallant armies massed beneath those tiny flags:

Record

without visualizing gallant armies massed beneath those tiny flags:

By the nineteenth of August, the line stretched from Antwerp in the north to Mulhausen in the south, passing through towns with names like Charleroi and Bastogne and Bitsch (which gave me a laugh), but it was a fluid front that changed from day to day; you could follow it like a general yourself and discuss it with other generals — here’s where I’d break through, here’s where I’d try to outflank them. In addition, you could be a general for whichever side you chose, because in the months that followed each side certainly gave us reason to believe

it

was right and the other was wrong. If the Germans were cutting off the breasts of Belgian women and the hands of Belgian babies, then the French were firing on ambulances and killing doctors; if the English served coffee laced with strychnine to German prisoners, then the Huns were shipping corpses back home to be made into soap. We suspected both sides were lying, of course, but the Allies’ stories were more inventive and entertaining in a horrible way than the ones the Germans concocted, so I guess even then we were beginning to lean in their direction — though we had no real quarrel with Germany and, if anything, distrusted the French who, we’d been told, “fought with their feet and fucked with their face.” Wilson said in his address to Congress that year that this was “a war with which we have nothing to do,” and we believed him, I suppose, even though we were already singing “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary” in the streets of Eau Fraiche, Red Reynolds’ orchestra having introduced the song in November — “the favorite of the first British Expeditionary Force,” he had proudly announced.

it

was right and the other was wrong. If the Germans were cutting off the breasts of Belgian women and the hands of Belgian babies, then the French were firing on ambulances and killing doctors; if the English served coffee laced with strychnine to German prisoners, then the Huns were shipping corpses back home to be made into soap. We suspected both sides were lying, of course, but the Allies’ stories were more inventive and entertaining in a horrible way than the ones the Germans concocted, so I guess even then we were beginning to lean in their direction — though we had no real quarrel with Germany and, if anything, distrusted the French who, we’d been told, “fought with their feet and fucked with their face.” Wilson said in his address to Congress that year that this was “a war with which we have nothing to do,” and we believed him, I suppose, even though we were already singing “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary” in the streets of Eau Fraiche, Red Reynolds’ orchestra having introduced the song in November — “the favorite of the first British Expeditionary Force,” he had proudly announced.

But if we identified (and I think we did) with the Tommies who were marching into France, we sure as hell did

not

appreciate what the British Navy was doing: seizing American ships and removing from their holds contraband items such as flour, wheat, copper, cotton, and oil; mining the North Sea; blacklisting dozens of American firms suspected of doing business with the Germans (none of

England’s

damn business, since we were, after all, neutrals); or even — and this really galled — raising the American flag on her own ships whenever German submarines were in hot pursuit. A lot of the German-American people in Eau Fraiche felt, and probably rightfully, that our diplomatic restraint in dealing with British violations of our neutrality merely indicated we weren’t neutral at all; we had, in effect, cast our lot with the Allies as early as the beginning of 1915. Well, maybe so. I myself was pretty confused, though I have to admit that by February, I began to lean toward the Allies again; that was when the Germans said they’d sink any enemy ship in the waters around the British Isles, and maybe a few neutral ships, too, if they couldn’t determine their national origin, which was sometimes difficult to do through the periscope of a submarine. Not only did they

say

they’d do it, but they actually

did

do it. and whereas searching ships and seizing merchandise was one thing, sinking them was quite another. I don’t think anybody in Eau Fraiche, not even those whose sympathies were with the Germans, condoned the actions of the U-boat commanders, who were already being pilloried in the press for their “wanton disregard of American life.”

not

appreciate what the British Navy was doing: seizing American ships and removing from their holds contraband items such as flour, wheat, copper, cotton, and oil; mining the North Sea; blacklisting dozens of American firms suspected of doing business with the Germans (none of

England’s

damn business, since we were, after all, neutrals); or even — and this really galled — raising the American flag on her own ships whenever German submarines were in hot pursuit. A lot of the German-American people in Eau Fraiche felt, and probably rightfully, that our diplomatic restraint in dealing with British violations of our neutrality merely indicated we weren’t neutral at all; we had, in effect, cast our lot with the Allies as early as the beginning of 1915. Well, maybe so. I myself was pretty confused, though I have to admit that by February, I began to lean toward the Allies again; that was when the Germans said they’d sink any enemy ship in the waters around the British Isles, and maybe a few neutral ships, too, if they couldn’t determine their national origin, which was sometimes difficult to do through the periscope of a submarine. Not only did they

say

they’d do it, but they actually

did

do it. and whereas searching ships and seizing merchandise was one thing, sinking them was quite another. I don’t think anybody in Eau Fraiche, not even those whose sympathies were with the Germans, condoned the actions of the U-boat commanders, who were already being pilloried in the press for their “wanton disregard of American life.”

I guess the sinking of the

Lusitania

could have been the last straw if President Wilson hadn’t kept his head. For me, it

was

the last straw; I was ready to go downtown with some of the other kids and smash Mr. Moenke’s store window (we had begun calling him “Monkey the Hun-kee” by then), but my father got wind of the scheme and told me if I left the house he’d beat me black and blue when I returned. I don’t know if it was my father’s warning or Mr. Wilson’s restraint that changed my mood of black rage to one of patience. In a speech on May 10, three days after the sinking, the President said, “The example of America must be a special example. The example of America must be the example not merely of peace because it will not fight, but of peace because peace is the healing and elevating influence of the world and strife is not. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right. There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight.”

Lusitania

could have been the last straw if President Wilson hadn’t kept his head. For me, it

was

the last straw; I was ready to go downtown with some of the other kids and smash Mr. Moenke’s store window (we had begun calling him “Monkey the Hun-kee” by then), but my father got wind of the scheme and told me if I left the house he’d beat me black and blue when I returned. I don’t know if it was my father’s warning or Mr. Wilson’s restraint that changed my mood of black rage to one of patience. In a speech on May 10, three days after the sinking, the President said, “The example of America must be a special example. The example of America must be the example not merely of peace because it will not fight, but of peace because peace is the healing and elevating influence of the world and strife is not. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right. There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight.”

Other books

Conquered: She Who Dares Book Two by LP Lovell

Sophie Morgan (Book 1): Relative Strangers (A Modern Vampire Story) by Treharne, Helen

Mary Coin by Silver, Marisa

The Wedding Affair (Rebel Hearts series Book 1) by Heather Boyd

Moth to a Flame by K Webster

The Coronation by Boris Akunin

Vanguard (Ark Royal Book 7) by Christopher Nuttall

SEALed Bride: A Bad Boy Romance (Includes bonus novel Jerked!) by Hamel, B. B.

His Need by Ann King

Post Grid: An Arizona EMP Adventure by Tony Martineau