Sophie and the Locust Curse (2 page)

The cattle market and the water tower flashed past and then the road came to an abrupt end. Chobbal galloped on eagerly into the sand. Looking back, Sophie saw the town’s enormous welcome sign written in French and Fulfulde:

BIENVENUE A GOROM-GOROM!

GOROM-GOROM WI’I BISMILLAHI!

Welcome to Gorom-Gorom, read Sophie, and she thought again of the

sauterelles

which were at that very moment on their way here.

What could they be

? Gigantic carnivorous plants, perhaps. That would give her Dad something to study. He was in his fourth year of research here and still had not found anything truly spectacular. But, thought Sophie, one of the

sauterelles

would probably eat Dad alive before he could even set up his microscope.

Gidaado’s voice in Sophie’s ear interrupted these morbid thoughts. ‘See that big white rock?’ he shouted, pointing with his staff.

‘Yes,’ yelled Sophie.

‘That’s Tondiakara, where the magicians go at night to sacrifice chickens.’

‘Lovely!’ said Sophie.

‘And you see that tree with the big round fruit hanging from it?’

‘Yes. It’s a calabash tree, isn’t it?’

‘Not just any old calabash tree,’ said Gidaado. ‘That’s the Sheik Amadou calabash tree. Sheik Amadou sits under that tree every day from sunrise to sunset, meditating on all the needless suffering in the world.’

‘So how come he isn’t sitting there now?’

‘He’s in hospital,’ said Gidaado. ‘A calabash fell on his head last Thursday.’

Sophie looked all around her at the desert. It was flat and featureless except for a few straggly thorn bushes. No

sauterelles

here yet, she thought. Unless they had excellent camouflage.

Chobbal let out a sudden snort of rage and began to buck up and down violently as he ran.

Sophie screamed. ‘What’s the matter with him?’ she shouted. She twisted round in the saddle and saw immediately what the matter was. A tall boy was riding close behind them on a bicycle, gripping the handlebars with one hand and Chobbal’s tail with the other.

‘Let go of him, Saman!’ Gidaado yelled.

‘

Salam alaykum

, skink-teeth,’ said the boy. ‘Did you wake in peace? Where are you and your white girlfriend going this morning?’

‘She’s not my -

let GO!

’ Gidaado leaned over and tried to prise the boy’s hand off Chobbal’s tail.

The boy hung on tight and laughed an idiotic high-pitched laugh. ‘What a freaky camel,’ he cried. ‘Does he always jump up and down when he runs?’

‘Gidaado,’ whispered Sophie. ‘Your staff.’

‘Ah yes,’ said Gidaado. He reached down as far as he could and inserted the end of his staff neatly between the spokes of the boy’s front wheel. Sophie winced and closed her eyes.

‘He’s okay,’ said Gidaado a moment later. ‘The sand makes a nice soft landing.’

‘Who is he?’ asked Sophie.

‘Sam Saman,’ said Gidaado. ‘He’s one of the Gorom-Gorom griots.’

‘He doesn’t like you much, does he?’

‘No,’ said Gidaado. ‘Saman and I go back a long way. We’d better watch our backs over the next few days, Sophie. Sam Saman is not the most forgiving griot in town.’

Sophie looked at her watch. ‘Talking of griots,’ she said, ‘do you think the Giriiji griots will start the

tarik

without you? We’re really late.’

Gidaado chuckled. ‘Start the

tarik

without me?’ he said. ‘Can you start to make bricks without earth? Can you start to make chobbal without milk?’

‘No.’

‘There you are then. My role in the performance of the

tarik

is essential. The Giriiji Griots would rather smash their

hoddus

over their own heads than start the

tarik

without me.’

A

hoddu

was a three-stringed guitar, used by griots to accompany their stories.

‘I don’t see why you are so indispensable,’ said Sophie. ‘I thought the

tarik

was just a list of names. Thig son of Thag, Thag son of Thog, and so on.’

‘You know nothing about the

tarik

,’ said Gidaado, piqued. ‘The

tarik

is not just a list of names. The

tarik

is like the spine of a man, the roots of a tree, the water in which a fish swims. When we are born we find it, when we die we become part of it. The

tarik

is the fabric of our life, a dazzling light shining down the well of History.’

‘The well of History,’ said Sophie. ‘Ooooh,

deep

.’

‘Mock all you like,’ said Gidaado. ‘You white people know nothing about History. Even if History was to fall on your head like Sheik Amadou’s calabash, you would not feel it. Even if History was bellowed in your ear by Furki Baa Turki, you would not hear it.’

Sophie had heard Furki Baa Turki bellow and she was certain that Gidaado was wrong. Furki Baa Turki was a town-crier and he had the loudest voice of all the criers in Oudalan. When he made announcements in Gorom-Gorom market, stallholders would plug their ears with sand and beg for mercy. Besides, thought Sophie, how dare Gidaado talk like that, as if she and her dad didn’t know anything about anything. She sat and fumed silently.

Perched behind her, Gidaado was singing under his breath. He’s practising the tarik, thought Sophie. I hope he forgets his lines in the middle of the ceremony.

Chobbal pounded onwards, rocking the children backwards and forwards on his hump. The sun climbed higher and higher in the sky until the sand of the desert glared like an overexposed photograph. After a long while Sophie reached into her shoulder bag and took out her water bottle and a small tub of sun-cream. Gidaado reached round her and took Chobbal’s reins from Sophie so that she could smear the cream on her face and arms.

‘Are you still mad at me?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ she replied, hiding a smile.

It was eleven o’clock by the time the children reached the fields of Giriiji, Gidaado’s village. Here the villagers’ crops stood tall and proud, thousands of millet plants, each plant bearing its precious cargo of crisp golden grains. Harvest time was not far away.

At last they arrived at a small group of mud-brick huts. Next to one of these huts the men and women of Giriiji were sitting on straw mats in the shade of a large acacia tree. Sophie heard the clacking of calabashes.

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Gidaado.

‘What?’

‘They’ve started the

tarik

without me,’ said Gidaado.

Chapter 3

‘

BAHAAT-UGH!

’ cried Sophie, camel-language for

stop

.

Chobbal skidded to a halt and Gidaado sprang off the hump backwards. He landed in a heap on the ground, got up, brushed himself down and ran over to the musicians’ mat where his three-stringed guitar was waiting for him. Sophie dismounted more carefully and went to join the spectators.

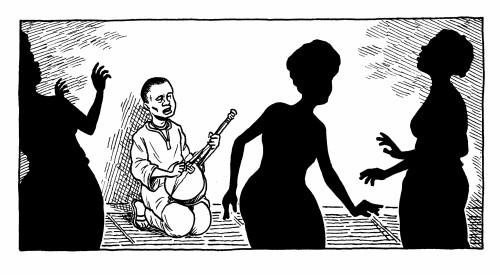

‘Amidou my brother, same father, same mother, flesh of my own flesh,’ sang the lead musician. Sophie recognized him as Gidaado’s Uncle Ibrahiim, the leader of the Giriiji Griots. He was flanked by Gidaado’s cousins Hassan and Hussein, who were bashing away happily on a pair of calabashes. Gidaado sat down behind them and began to pluck his

hoddu

.

‘Amidou, husband of Bintu the Beautiful, brother of Alu the Fearless,’ sang Uncle Ibrahiim. ‘Alu the Fearless who wrestled a lion and did lots of other brave and brainless things.’

‘That’s right!’ shouted Gidaado.

Sophie noticed Gidaado’s grandmother sitting on one of the women’s mats. She had great long earlobes and her skin was as wrinkly as a walnut. Her eyes were half-closed and she nodded to the calabash beat.

‘Amidou and Alu, sons of Hamadou, son of Yero the son of Tijani,’ sang Ibrahiim.

‘That’s right!’ shouted Gidaado.

‘Tijani, whose camel Mad Mariama ran faster than the harmattan wind.’

‘That’s right!’

It seemed to Sophie that Gidaado’s role in the

tarik

was slightly less glamorous than he had made out. Perhaps the best was yet to come.

‘Tijani son of Haroun.’

‘That’s right!’

‘Husband of Halimatu the Horrible, who could make music with her armpits.’

‘That’s right!’

‘Son of Salif, son of Ali, son of Gorko Bobo.’

‘That’s ri- ‘

‘STOP!’ shouted the chief.

Uncle Ibrahiim stopped singing and blinked rapidly as if waking from a trance. The twins’ calabashes ceased their clicking and clacking. Gidaado laid down his

hoddu

and stared at the chief in amazement. A woman emerged from the nearest mud-brick hut, holding a tiny baby at her breast. She quivered with rage and pointed a long thin forefinger at the chief.

‘How dare you interrupt the

tarik

, you son of a skink!’ she cried.

The villagers gasped. A skink was a large lizard and not a nice thing to call anybody, let alone a village chief.

‘Bintu,’ hissed a nervous-looking man in the front row of the audience. ‘Bintu, don’t talk like that.’

‘How am I supposed to talk? He has shattered the

tarik

and brought shame on the memory of all our ancestors.’

The villagers gasped again. This was a serious accusation. All eyes now were on Al Hajji Diallo, chief of Giriiji.

Slowly the chief raised his eyes to heaven. ‘Look!’ he cried.

Everyone looked. Far away in the west, a pink cloud was gathering in the sky, thickening and getting closer, like a dust cloud. Here in the desert a dust cloud was usually good news, indicating the arrival of rain.

‘

Zorki

,’ said Uncle Ibrahiim.

This was no dust cloud. As it approached, Sophie could see that the cloud was made up of millions of tiny dots, pink and flickering and strangely beautiful.

‘

Zorki

,’ said the woman with the baby.

‘What is it?’ asked Gidaado’s grandmother loudly. ‘Why has the

tarik

stopped? What is going on?’

‘The pink death,’ said the chief. ‘The pink death is coming!’

‘

Zorki!

’ shrieked Gidaado’s grandmother.

The dots swarmed towards the fields and began to dive. They fell like rain, no longer dots but living creatures now. The air was thick with legs and wings and mandibles. So these are the

sauterelles

, thought Sophie.

Locusts

.

*

In no time at all Sophie found herself sprinting through the millet plants alongside Gidaado. She glanced down guiltily at the long curved scythe in her hand.

Never mess with knives

, her dad was always saying. If he could see her now his glasses would steam up and he would no doubt give her that lecture about Hibata Zan running to school holding a pair of scissors. She wore an eye-patch to this day, poor girl.

‘Gidaado,’ said Sophie as they ran. ‘Why do they call it “pink death”?’

‘Well,’ said Gidaado. ‘The locusts are pink. And by eating the harvest they bring - you know.’

‘I see.’

Arriving at Gidaado’s field, Sophie handed Gidaado one of the scythes and he quickly showed her how to harvest the millet. Stalk in your left hand, scythe in your right hand and

slice

. ‘Now you try,’ he said.

Slice, slice, slice

, went the two scythes, and the millet stalks fell this way and that. On every side Sophie heard the slice and crunch of other harvesters. All the people of Giriiji, young and old, were working together to save the millet. After all, this was their food for the coming year.

A locust landed on a stalk right in front of Sophie, hugged the millet with its jointed legs and started munching. Another flew in Sophie’s face; she screamed and batted it away. She sliced the stalk with her scythe but immediately two more locusts landed on it. Sophie dropped the stalk and stamped on them.

Crunch. Crunch

.

The insects were all around her now, chomping and chattering. They were on her clothes and in her hair. There was not a single head of millet that did not have two, three, four locusts clinging to it, even the harvested millet lying on the ground. Sophie watched the locusts devour Giriiji’s millet crop and she blinked hard to stop herself bursting into tears.