Stars of David (43 page)

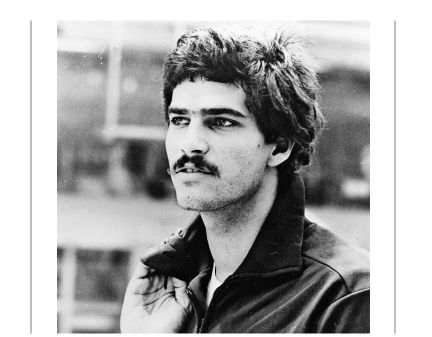

Mark Spitz

A. B. DUFFY/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

MARK SPITZ WAS THE FIRST, and remains the

only

, Olympic athlete to win seven gold medals in one yearâ1972âeach one breaking a world record. The fact that this champion swimmer was Jewish and triumphed in Munich, Germanyâforty-five minutes from Dachauâwas history-making enough. But tragic events made it even more poignant: The same night he won his seventh prize, nine Israeli athletes were taken hostage by Palestinian gunmen, who killed them the following day.

“I was a Jewish swimmer at the Munich Olympic Games,” Spitz recounts by phone from his Los Angeles home. “We were fifteen miles from Dachau, and here was this Jew at the games. It's important to remember that 1972 was the coming-out party for Germany; the nation was saying, âWe're here and we're not like the regimes of thirty years before. These games will be the perfect example that the German people have come full circle.' And then I go and win seven gold medals. And that night, the terrorists jump the fence and later kill eleven Israeli athletes. So there was simultaneously the triumph of my accomplishment and the tragedy of the Israelis; these two were inextricably linked.”

The day after Spitz's gold sweep was September 5, 1972, and Spitz, then twenty-two, was supposed to be at a press conference talking about his feat. Instead he was rushed out of the country because law enforcement feared he might be in danger. “I left that evening because of the ensuing uncertainty of what was going on,” says Spitz. “I woke up in LondonâI was with my swim coachâand read about the killings in the paper. It was unbelievable.”

He says the symbolism of these events only intensified the public focus on his religion. “My being a Jew was put into the limelight in a very big way,” says Spitz. “I had a calling of the guard to step up to the plate and recognize that I was Jewish.”

Not only were journalists and Jewish groups bombarding him; Spitz says even the president was preoccupied with his affiliation. Recently released tapes of Richard Nixon's conversations, publicized in December 2003, show that Nixon deliberated over whether to make a congratulatory call to Spitz. “There was a quote from Haldeman talking to Nixon,” says Spitz. “It was about how Nixon painstakingly vacillated about whether to call Mark Spitz after he won seven gold medals but elected not to do so. Do you know why? He assumed, because most Jews are Democrats, that I supported George McGovern. This was September of 1972âtwo months before the electionâand he didn't want to align himself with Democrats by congratulating a Jewish athlete because Spitz was probably a Democrat,” Spitz says with a chuckle. “The irony is that I've been a registered Republican since I've been able to vote.”

Spitz, fifty-five, grew up in California and Hawaiiâwhere his father, Arnold Spitz, put his son in the water at age two. “I was bar mitzvahed on December 7, 1963, the anniversary of Pearl Harbor,” says Spitz. “I was very nervous that day, but there were only two people who knew I made a mistake during the service. I remember that because I was embarrassed. In my haftarah portion, I chanted one line twice. Only my grandfather and the rabbi knew that.”

He started competitive swimming before he was ten and was named the world's best ten-and-under swimmer. At fifteen, in 1965, he went to Tel Aviv for the Maccabiah Gamesâan annual contest created to celebrate and encourage Jewish young people in sportsâand he won four gold medals. A year later, Spitz went to compete in Germany. I ask him if it felt strange to be there as a Jew. “In 1966 I was sixteen and the war had only been over for twenty years,” Spitz says. “The thought did occur to me that anyone I met in their forties could have been a Nazi at one time. It was weird to walk into a bakery and know that, twenty-odd years ago, I would have been pulled into the street and shot . . .” He pauses. “Of course your humor about that situation is a lot different when you're sixteen or seventeen because nothing happens to a seventeen-year-old.”

Years later, in 1985, Spitz was asked to return to the Maccabiah Games to carry the torch. “There were three little girls, thirteen years old, who ran behind me,” he recalls. “Each of those little girls' mothers was pregnant when I was in Munich. Each of their fathers was killed as one of the Israeli athletes. That was pretty emotional.” Spitz is quiet for a moment. “That was the best time for being a Jew.”

But Spitz says his status as a Jewish role model never fueled his athleticism. “I embraced the fact that I'm Jewish. Did that have an influence on me athletically? Zero. Does it influence younger people? Yes. Because it says that being a Jew is not something that limits you physically and athletically.”

I ask him why he thinks there are so few Jewish sports stars. “There are fewer sports stars only because there are fewer Jews,” he scoffs. “We have the same number of Jewish athletes proportionately as non-Jews have. Does that mean that Catholics are better than us? Hell no. It's just sheer numbers.”

What about the stereotype that Jews go on to be doctors and lawyers, that they favor more intellectual pursuits? “That's not because we're smarter,” says Spitz. “If you keep telling your kids to hit the books, even a dummy can get smarter.”

Spitz himself was preparing to go to dental school before he abandoned that plan after the 1972 Olympics. These days, Spitz works as a stock broker and financial analyst and gives inspirational speeches. He's been married to “a Jewish girl,” as he puts itâSuzy Weinerâfor thirty-two years. “Early on, before I even got married, I thought about how I would raise children if I were to marry outside the religion. How would they identify with who they are and would it be good to have a split situation, where they were raised with both religions involved? I realized that that wasn't something I would be comfortable doing. So perhaps it's prejudiced, but I focused on marrying someone Jewish.”

Both his sonsâMatthew, twenty-four, and Justin, fourteenâwent to Stephen Wise religious school starting from kindergarten and became bar mitzvah. “The funny thing is that it becomes kind of contagious,” says Spitz. “When you're around a community that embraces religion, you embrace it more, too. I've been participating in this in a big way. I'm a big proponent now. I used to hate going to High Holy Days services; as soon as I got there, I was counting the minutes till I could leave. Now I look forward to going. Maybe I'm older and not as fast paced as before. Also, I'm an example for my kids. I enjoy it.”

Though he never experienced any overt anti-Semitism, he's still bothered by the fact that he was not asked to participate in the opening Olympic ceremonies in either 1984 or 1996. “Look, one of the greatest honors bestowed upon someone in the Olympic games is that at the opening ceremonies they honor past notable Olympians and their accomplishmentsânot just the medals they won but the way they've represented their sport. These athletes would participate in the opening ceremonies, either running the torch, lighting the cauldron, or carrying in the Olympic flag. In the Olympic games in L.A. in 1984, I was thirty-four. They had two people involved in carrying the torchâboth of them deserving as far as their credibility and athletic accomplishments. But Mark Spitz wasn't there.

“In the 1996 Olympic games, there were three people involved in the opening ceremonies and the lighting of the torch. And in no cases were any of them Jewish. I guess Mark Spitz didn't win enough medals to be included in that fraternity. I leave it to you to figure out why. Does it bother me? Would I have liked to? Sure. I didn't compete in the Olympic games just to win medals, become known as a Jew, and then be asked to run in the Olympic flame; I did it because I love the sport. But I noticed.

“But hey, I'm still not dead,” he adds. “There's still a chance.”

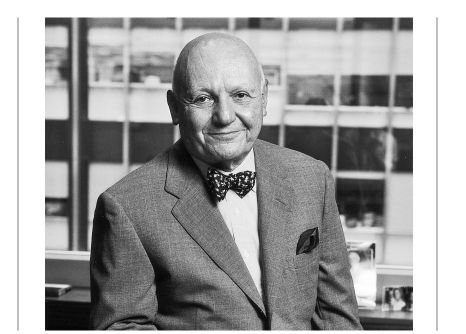

Alan (Ace) Greenberg

ACE GREENBERG PHOTOGRAPHED BY WAGNER INTERNATIONAL

JOHN H. GUTFREUND, the former CEO of Solomon Brothers, once described Alan (“Ace”) Greenberg, the former CEO of Bear Stearns, this way: “Ace is by the numbers, very black and white . . . He sees prices, he's not clouded by emotionalism.”

You can say that again. My interview with him is a dramatic confirmation of that characterization. This highly respected titan of Wall Street, who made $16.2 million in 1994 and who built Bear Stearns from 1,200 employees (and $46 million in capital) into the fifth-largest investment bankâ with 10,300 employees and $1.4 billionâtalks in bullet points instead of paragraphs, without a wasted word or a trace of sentiment.

From his seat on the bustling trading floor (he prefers sitting amid the din to staying in his office), his strong bald head stares straight aheadâ military style. He doesn't even glance at me sitting next to him when he answers my questions. Jacketless, in a monogrammed blue shirt that strains against his former football player's frame, Greenberg holds a lit cigar in his meaty grip. Its smoke fills the air and probably violates company policy.

Greenberg isn't rude; just abrupt. It's difficult to describe the staccato exchange, so perhaps an excerpt is the best illustration:

Q. Did you go to synagogue and Hebrew school growing up?

A. The whole works.

Q. Was that important to your parents?

A. If I had my choice, I wouldn't have done it. I would rather have played football.

Q. The fact that you excelled at footballâwas that something other Jewish boys were doing?

A. No. I was the only one. For years, in fact. Obviously it helped me a lot socially. In high school. There was anti-Semitism, no question about it, in Oklahoma City.

Q. Can you describe that a little more specifically?

A. Well, the high school fraternities didn't allow Jews in them. That wasn't easy for me. But I played football, so that kind of made up for it.

Q. Was there some sense that people gave you special treatment despite your religion because you were an athlete?

A. Yeah, I think the girls did.

Greenberg attended the University of Oklahoma on a football scholarship, and after a back injury transferred to the University of Missouri, where he received a bachelor's degree in business in 1949. When he was applying for entry-level jobs on Wall Street, he was shut out of the white-shoe firms because he was Jewish. Only Bear Stearns would take him. “In those days, it was pretty tough,” Greenberg says. “But that's changed.” Was the prejudice explicit? “Well, there was a certain amount of anti-Semitism even among Jews then. Some of the investment banks in New York that were prominent were Jewishâthey were basically run by German Jews. But they weren't exactly looking for me either.”

The war had recently ended when he began his professional life, so I ask him if the Holocaust had a strong impact on him at the time. His response is trademark efficient and unrevealing. “No, I don't think so. I obviously felt very bad about it.”

Over the fifty years that Greenberg has spent advising prominent investors such as Henry Kravis and Donald Trump, he's garnered respect for his prudent, unvarnished counsel and his quirky pursuits. He is a nationally ranked bridge player and an ardent devotee of archery, pool, whittling, dog-training, and the yo-yo. Not to mention magic tricks. He's spent many Saturday mornings in Reuben's Delicatessen honing his sleight-of-hand before other “expert” amateurs. “That has nothing to do with being Jewish,” he says with a chuckle. “The rabbi didn't encourage it.”

Greenberg keeps glancing at his telephone, as if willing it to ring so he can get back to work. Suddenly it obliges and Greenberg seizes the receiver. “Hello?” Apparently that's standard procedure at his company: Greenberg believes no phone should ring twice before it's answered. There are other Greenberg tenets that have become Wall Street lore: his announcement that paper clips would no longer be purchased by the companyâemployees should reuse the ones from incoming mail; interoffice envelopes should be conserved by licking the flap alternatively left and right. Employees must pay the difference if they upgrade to first class, and there are no corporate jets or limousines. Greenberg used to distribute half-kidding memos with tips on frugality, penned by an “advisor and mentor” he invented named Haimchinkel Malintz Anaynikal. For example: “The time to stop stupidity and be tough on costs is when times are good. Any schlemiel and most schlamozels try to cut costs when times are bad.” Or Anaynikal's guidance on the envelope-licking strategy: “If one has a small tongue and good coordination, an envelope could be opened and resealed ten times.”

On a more sober note, Greenberg has for decades required that his top managers donate a portion of their income to charity. “Four percent,” Greenberg says. “All senior managing directors. There are about six hundred of them.” Has any employee ever balked at that? “One person. In the whole time we've done it.” What happened to him? Greenberg grins. “Well, he's not a senior managing director anymore.”

Greenberg believes there's an obligation to give back. “I think it's called a Jewish tax,” he says. He has contributed generously to many college scholarships and charities such as the United Jewish Appeal-Federation. He's also established a school and a health center in Israel. “I used to joke, âWhen I grow up I want to be a philanthropist because it seems to me they always have a lot of money.' So that was my goal: to be a philanthropist.” Some of his causes are not exactly mainstream: for instance, his support of a dwarfism program at Johns Hopkins Hospital, or his one-million-dollar donation to New York's Hospital for Special Surgery to offer Viagra to the poor. Greenberg laughs when I inquire about that one. “At that time, Viagra wasn't covered by any of the insurance companies, and I felt it was just something that I could do for people who couldn't afford it.”

The phone rings again and the boss seizes it. “Hello? Hi, Gail . . . So what can I do?” Greenberg is famous for cutting to the chase:

What's the

bottom line?

He discourages small talk, and doesn't seem to engage in it himself. He's even alert to distractions: When I try to rummage unobtrusively in my bag for my last page of questions (he's running through them like water), Greenberg notices and barks, “What do you need?”

Q. Once you had your own family, I wonder to what extent you maintained the childhood traditions with which you were raisedâ?

A. Maintained them.

Q. How important was it to you that your two children feel Jewish?

A. Very.

Q. How did you pass that on?

A. Oh, just in conversations with them, trying to explain the culture and how important I felt it was.

Q. Was it important to you to marry a Jewish woman?

A. My first wife was, my second wife is not.

Q. And your childrenâ?

A. My daughter married a Jew; my son did not and they got a divorce. I don't think religion played any part in it whatsoever.

Q. Did you care if they married outside their religion?

A. No. I wanted them to just be happy. Sometimes Jews marry Jews and they're unhappy, right?

A former bachelor-about-town, escorting the likes of Barbara Walters or Lyn Revson, Greenberg has been married since 1987 to Kathryn A. Olson, nineteen years his junior, who was until recently a supervising attorney at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University in New York, specializing in the legal rights of the elderly poor. Press accounts say Olson has softened Greenberg.

A trader named Mitch stops by Greenberg's work station. “Can I get you to do a quick meet-and-greet?” he asks.

Greenberg replies: “Sure; what time?” Mitch: “Say, two-thirtyish?” Greenberg seems delighted: “The guy from John Hancock? That's fine. Shake-and-bake, right? Okay, Mitch; that's fine.”

I see that my sliver of Greenberg's attention span is thinning, but I want to finish by asking one mushy question: Where does being Jewish fit into his sense of self? I'm surprised by his instantaneous response: “Well, it's first and foremost. Everybody knows I'm a Jewâthere isn't anybody I do business with who doesn't know it. If my name was O'Reilly, I might be embarrassed by somebody saying something against Jews, but it doesn't happen with a name like Greenberg. They may think it, but they don't say it.” He laughs and stamps out his cigar. I thank him for the interview. “That's it?” He looks genuinely surprised. “If you have any questions, call me.”