Stars of David (39 page)

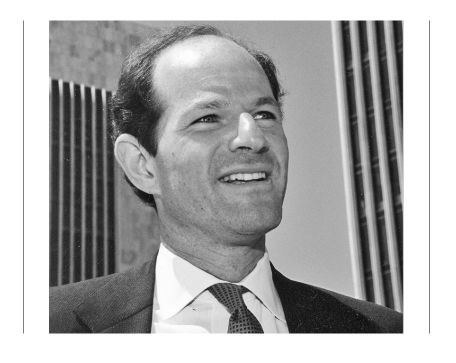

Eliot Spitzer

ELIOT SPITZER, whom the

New York Times

has called “the most prominent Attorney General around,” who is gearing up to declare his candidacy for New York governor when I meet him, is in his Manhattan office during a snowstorm, looking immaculate in a blue suit, white shirt, and black shiny shoes. Of course, he's at his desk in a blizzard. Article after article has been written about Spitzer's ambition and tenacity, his trophy diplomas from Horace Mann (tennis team captain), Princeton (student body chairman), and Harvard Law School (Law Review); his election at age thirty-nineâin 1998âto the office of New York State attorney general, and lately, his headlines for taking on corruption in the financial and insurance industries. He's been touted for rousing a tired office into becoming an aggressive muckraker.

As for Spitzer's Jewishness, he says it can be found in his work. “On one level it pervades everything that I do,” he says, sitting on a government-issue blue chair on a government-issue blue carpet. “I'm always trying to figure out what is the best way to use the capacity of this office to do something that's useful. And it's not as though one's deepest values pervade every decision like that, but to a certain extent, when I'm thinking about, âDo I want to get involved in this issue, and if so, why, and whom do we help,' to a certain extent that does go back to my sense of what the core values of Judaism are as I understood them. I do have a sense that when I set priorities and try to articulate what it is we're doing, the reasoning stems concretely from my Jewish ancestry, as my dad conveyed it to me.”

His father, Bernard Spitzer, a civil engineer who became enormously wealthy in real estate, instilled his son's hustle and acumen. (Spitzer describes his relationship with his motherâa literature professor at Mary-mount Manhattan Collegeâas “the classic son-mom type,” saying “She is just as intellectually acute, but was always more emotionally driven.”) Family dinners in Riverdale, New York, were a place for discussion and debate: The three children took turns bringing an issue to the table. (They were also quizzed on sightseeing during family vacations.)

When I ask Spitzer how he would link Jewish values to achievement, he laughs: “I'm neurotic.” He confesses that he's inherited his parents' premium on accomplishment. “I'm not necessarily comfortable with self-analytical stuff, but it's hard, I suppose, to deny that when I was growing up, there wasn't a certain set of expectations, or that I haven't passed that on to my eldest daughter at this point. My younger two are still a little youngâbut even my eight-year-old, who is in third grade, hasn't missed a spelling word on her weekly spelling test all year. There is a very real sense that we expect performanceâalways shrouded, of course, in the cliché that âWe want you to do the best you can do.'”

The academic pressure with which he was raised and is raising his own children, however, does not apply to his Judaism. Spitzer's parents, despite Bernard's training as a cantor (“He has a great voice,” Spitzer says), did not take him to synagogue regularly or insist he be bar mitzvah, which his mother still regrets. “Once or twice she has voiced misgivings that I wasn't bar mitzvahed,” Spitzer says, “but when I ask her why, it sort of doesn't go anywhere. So I don't know quite what to make of it.” It's clear that Spitzer too feels ambivalent. “There are moments where I wish I'd had a more formalistic training. One thing that I think is symbolic of how my dad viewed it was that instead of my being bar mitzvahed, he wanted me to read Abba Eban's

History of the Jews

. That gives you a certain insight into what he considered the important aspect of the maturation process. And if my children are not bat mitzvahed, they're going to read that book, too. Because I think understanding the history and the cultural predicates of Judaism is critically important.”

Spitzer's own religious parenting has been complicated by the fact that he married Silda Wallâa law school classmateâin 1987: “She's not Jewish,” he says, “which is an issue that we've grappled with in terms of the kids.” (They have three daughters ranging from ten to fifteen years old at the time we meet.) “I obviously feel that the children will be Jewish; they're going to Horace Mannâa school that's predominantly Jewish, they're growing up in a Jewish environment, a Jewish culture.” I ask if he and his wife discussed the matter of religion before they got married. “Yeah,” he says with a smile. “You know how conversations like that go. To put it in the context of a corporate transaction, it probably wasn't the deal-breaker on either side, so it sort of got pushed aside and we delayed. Even the closing documents didn't address it.” So, the hurdles are being dealt with as they go along? “Yes.”

He says the girls go to church only when they visit his in-laws in North Carolina. I ask if that makes himâ“flinch?” he finishes my question. “I grimace. But I bear it.” He seems to take comfort in the fact that at home, they're surrounded by other Jews. “My view is they're here in New York and they're growing up in a culture that is essentially a transmission to them of Jewish values. I want to take them to Israel. I don't know when I will. I've resisted going on all the political junkets; I don't want to be there with ten elected officials. I think that would cheapen it.”

I wonder if he thinks his children consider themselves Jewish. “I hopeâ” He pauses. “They probably consider themselves

confused

, but that's like all kids. I think they are very conscious of the fact that they are Jewish, but Mommy might not be, but that's okay.” All three daughters attend Hebrew school, but one has already taken her father's path. “My eldest is not being bat mitzvahed. The younger two, it remains to be seen.” I asked if it was his daughter's decision. “As parents, there are choices that you lead your children to; this one I really had a more hands-off attitude because I didn't want to force it on her because I didn't think that would be terribly productive.”

In addition to celebrating Hanukkah, the Spitzers do have a Christmas tree every year. He says he doesn't recall his parents ever cringing at the sight. “They know that nothing I'm doing is a rejection of how they raised meâwhich I think would evoke a different emotional response from a parent. If they had been much more rigorous in their purely religious training with me and I had gone somewhere else on the spectrum, that might have been difficult. But what we're doing is very much in sync with where they were.”

Even without the religious foundation, Spitzer says ethnic pride fuels his professional focus on fair treatment. “We have been able to represent immigrant groups who came hereâWest Africans, Mexicans, Asiansâ who have been taken advantage of by a system where they were denied rights because they were easy targets. We are a nation of immigrants, very much like Jews in the Diaspora, who have needed to migrate, to find a home. That sense of providing opportunity is what America is all about. It's the common theme that I hope traces through much of what we do.”

He confesses there have been moments where his Jewish pride has been tested. “I wouldn't be truthful if I didn't say that occasionally there have been a couple cases where the defendants were Orthodox Jews. There was a high-profile fraud case, for example, and within a certain circle of the Orthodox community, there was a lot of anger against me. People said, âWhat are you, one of those Jew-hating Jews?' This defendant was someone who had given away a lot of money to the community, but he'd stolen the money he was giving. At the end of the day he pled guilty to every count of the indictment; the evidence was

that

overwhelming. So I went back to the people who had come to me and who had said things that hurt. I never let on that it hurt, but it hurt because I felt it was not only unfair but it was wrong, and it was wrong for them as Jews to think in that way. It bothered me. I looked them in the eye and I said, âNow you understand: you were wrong. At least I hope you do, because it was the wrong way to judge me and it's bad for us as Jews when we react that way.'”

I'm talking to Spitzer before the 2004 election and before his subsequent announcement that he's running for governor of New York. He won't comment on whether he dreams of the presidency, as someâ including his fatherâhave speculated, but he does say it's “stupendous” that Senator Joseph Lieberman could be taken seriously as a candidate without his religion being the focal point. He also gets a kick out of revelations that Senator John Kerry has Jewish blood. “Next time I see him, I'll say, âHey! We're closer than we thought.'”

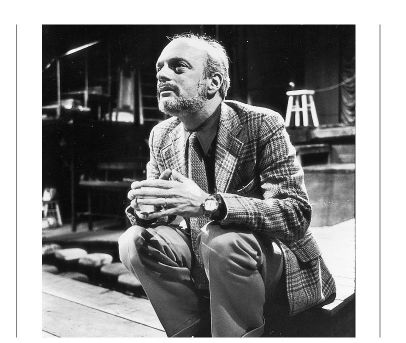

Harold Prince

HAROLD PRINCE PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1974 BY JILL KREMENTZ

WHEN PRODUCER/DIRECTOR HAROLD PRINCE, who's helped create such Broadway classics as

West Side Story, Damn Yankees, Sweeney

Todd, Evita

, and

Phantom of the Opera

, was approached in 1964 by writers Sheldon Harnick and Jerry Bock to direct

Fiddler on the Roof

, he refused. “I didn't

get

any of it,” Prince says, swiveling around in his leather office chair. “So I said, âI won't do it. As far as I'm concerned, you should do everything in the world to get Jerry Robbins.' When they asked Jerry, he said, âI'll direct it if you get Hal Prince to produce it.'”

Fiddler

turned out to be the longest-running musical of its time. “But all during the entire rehearsal process, I still didn't get it,” Prince repeats. “Harnick gave me a book about the shtetl, and Bock made me look at Maurice Schwartz's film version of

Tevye, the Milkman

[the story by Sholem Aleichem on which

Fiddler

was based]. I steeped myself in a lot of it, but it wasn't coming from in here.” Prince knocks on his chest.

As the descendant of German Jews, Prince explains, his gut connections did not come from the poor Russian villages that

Fiddler

portrays. Yet somehow Prince and his collaborators managed to craft the definitive Jewish portraitâa show whose musical score, including “Sunrise, Sunset,” have become almost part of the religious canon.

“I think one of the things you have to realize is it was a huge success because people thought it was about family,” Prince says, taking off the signature glasses that often sit perched on his forehead. “It was a hit all over the world. And when we finally reached nine thousand-whatever performances, I brought all the Tevyes to New York from all over the worldâ every actor who had ever played the role. And at the end of the show, they came out on stage in costume singing âTradition' [the show's opening song], one after another after anotherâa Japanese Tevye, a German Tevye, a Mexican Tevye. There they all were.” Prince smiles at the memory. “The show was a success because for non-Jews it wasn't Jewish: It was about family.”

However universal the appeal, however, some Jewish audiences were unhappy about it. “When

Fiddler

opened, Jerry Robbins gave his first dance teacherâan old, old manâthe role of the rabbi. And he was a kind of befuddled, humorous, adorable character and Jerry loved him. The board of rabbis didn't. They sent me a telegram threatening to boycott the show if we didn't change that character. I wrote back and said, âWe have no intention of changing that character; it's created by Mr. Robbins and the authors with great affection.'”

I ask what exactly the board of rabbis objected to. “They thought he was buffoonish,” Prince explains. “Yes, he was an addled little rabbi. But he was adorable. You know what the character's signature gesture was? Anytime anybody in the village came to him for advice, he'd take the big book and leaf through it madly, looking for answers. And then he would do a Solomon-like thing: â

You're

right and

you're

right!'

“The New York board of rabbis started sending me a telegram regularly every few hours for delivery. It was harassment. I barked back, âIf you continue this, I will publicize it. It's narrow-minded foolishness; stop right now.' And they did. But for a moment there, I said to myself, âHoly God, are they going to deliver telegrams every two hours forever?'”

Prince's own Jewish affinity was ignited much more deeply decades later by a far less successful musical he directed called

Parade

. It told the true story of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory manager who was falsely accused of raping a white girl in Atlanta in 1913 and ultimately hanged for it by an angry mob. “I felt

Parade

was as close as I could get to doing

my Fiddler

,” says Prince. “And when it was rejected in terms of popular entertainment, I was very hurt. Because I loved the show and still do. Its reception could have put it right where it belonged, but instead, it was completely unappreciated where it mattered.”

I ask how it connected him to his Jewishness. “What did it mean to me? Everything,” he says. “I related to Leo Frank. But see, that's a southern family.”

Prince has southern roots because his German ancestors migrated to El Paso, Texas, stopping in New York along the way. His mother's great-grandfather, Adolph Rubin, was the second cantor of New York's Temple Emanu-Elâ“He wrote some hymns that they still use today,” Prince says. Adolph Rubin's daughter, Ella, married and moved to El Paso, “where her husband became the president of the Bank of Juárez, Mexico!” Prince clearly gets a charge out of this. “So you see, it's kind of a weird Jewish family story!”

Harold Prince is less enthusiastic when asked about his father, Harold Smith. “I never talk about him,” Prince says matter-of-factly. “My mother remarried when I was three years old, so I was raised all of my life by a guy named Milton Prince who was on Wall Street. My father was a guy I never cared much for, to be honest with you. And I never cared for his family.”

I remark that “Smith” doesn't sound Jewish. “I think it may have been Goldsmith before,” Prince explains.

Prince grew up in New York Cityâattending the Dwight School when it was called the Sachs School: “We were all Jewish there except for Truman Capote,” Prince says with a laugh. “He graduated a year ahead of me.”

His family never went to Temple Emanu-El for services, but to this day, they have two seats that are always set aside for them. “They're lousy locations, because they know I never come,” Prince says with a laugh. “But I tell you what: I did repay them once.” He's referring to the time the head rabbi asked Prince to direct a show to celebrate the temple's 150th anniversary. “There was a moment where I thought, âYou owe them this.'” Prince smiles. “âYou haven't been in the doors for decades, even though someone is singing your great-grandfather's hymns every year; you owe them this.'” The rabbi said he wanted the celebration to be a revue in honor of three temple alumni. “I said, âWhich three?'” Prince recounts, “And he said, âJerome Kern, Irving Berlin, and Richard Rodgers.' I said, âYou bet I'll do it.' It was a very sweet evening. And that's the last time I set foot in the temple.”

When one is reminded of those Broadway greatsânot to mention Stephen Sondheim, with whom Prince collaborated on such musicals as

A

Little Night Music

and

Sweeney Todd

âit raises the question of whether Jewishness might fuel creative talent. “Most people who are high accomplishers come from behind some psychological eight ball where they feel disenfranchised and they have to create something,” Prince says. “Certainly that's true of me. It's almost true of almost everybody I know. There's that neurotic âyou either sink or you swim, and swimming's better.' So I think what you're talking about is grit and resilience, and yes, fantasy and escape. The art went to some place of escape. It is an advantage not to be born with a silver spoon in your mouth. It just is.”

I pass along what Sondheim told me, in our conversation for this book, that Jews are “smarter,” and how he challenged me to name a great gentile musical theater composer other than Cole Porter. “I'm so reluctant to ever go where Steve went, which is to say âWe're the best.' Somebody else better say it. Somebody who isn't Jewish. Every once in a while you find yourself in a room full of accomplished Jewish people and they feel too superior. I don't think anyone should feel superior.”

And yet he does connect the success of many Jews to their ethnicity. “I could say something very arrogantâthough I don't approve of it: It's a hell of an elite club. I don't take huge pleasure in saying, âLook at us on Broadway in the musical game: We're Jewish.' But the facts are there. And all I can ever think is so much of this has to do with how a race of peopleâor a religious groupâdealt with deprivation. They actually took an isolation that was thrust on them and turned it into an advantage. And in that isolation, they saw to it that people were educated, that their priorities included medicine, law, literature, the arts. They were passionate about taking a disadvantage and turning it to a cultural advantageâtheir advantageâand that's huge. Because there's another way to deal with this kind of deprivation. There are other races and religions out there and they don't always turn adversity into creativity. And we'll let it go at that.”