Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (2 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

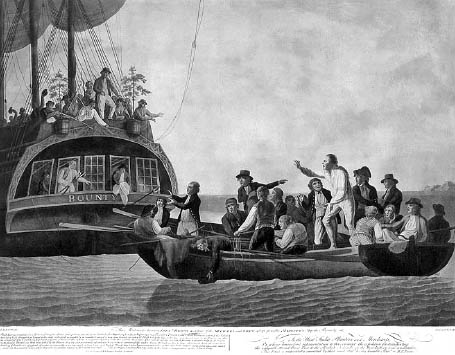

One of the notable characteristics of this era was sheer bloody-mindedness in the face of incredible odds. When Sir Richard Grenville chose to stand and fight the Spanish in 1591 he was outgunned and outnumbered 53 to one. William Bligh achieved one of the most remarkable feats of seamanship and survival of all time: after mutineers set him adrift in an open boat, he completed an epic voyage across the Pacific Ocean without the loss of a single man. At the Battle of Trafalgar the diminutive French captain Jean Lucas and his crew fought heroically in

Redoutable

as their decks were torn open and guns shattered. When he eventually surrendered just one mast remained upright. The butcher’s bill was horrendous – 88 per cent of the crew were either killed or injured.

It was an age when a barren rock could be commissioned as a sloop of war, when a duel to the death could be fought by a naval officer over a dog, and when the French could say of the English that they felt it wise to execute an admiral from time to time

pour encourager les autres

. And who could not smile today at the gritty humour of the handsome Irish master’s mate Jack Spratt? When told that his badly mangled leg must be amputated he refused and pointing to his good leg declared, ‘Where shall I find a match for this?’

Facing almost certain death at sea, William Bligh is cast adrift by

Facing almost certain death at sea, William Bligh is cast adrift byBounty

mutineers

.

T

HE WAR OF JENKINS’S EAR

It may be history’s most oddly named conflict. Captain Robert Jenkins was an English sea captain whose ship

Rebecca

was boarded by the Spanish as he sailed back to England from Jamaica in 1731. During the ensuing skirmish one of Jenkins’s ears was severed and he pickled it in

a

bottle. Although he complained of his treatment on his return, that was pretty much that for another seven years.

Friction had been increasing between the English and Spanish over trade rights in Central America, and in 1738 Jenkins was summoned to Parliament to recount his story and produce the now shrivelled body part. This resulted in outrage throughout the country but more importantly it was an excuse to teach the Spanish a lesson. England declared war on Spain the following year – and thus began the War of Jenkins’s Ear.

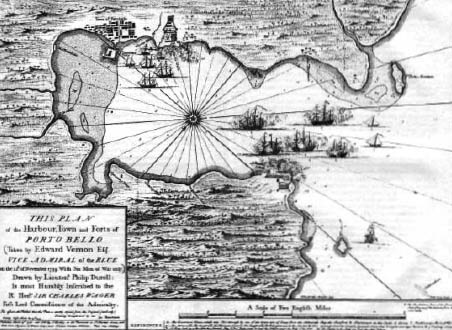

Admiral Vernon was ordered to ‘destroy the Spanish settlements in the West Indies and distress their shipping by every method whatever’. He took the city of Porto Bello in November 1739, a victory that was greeted with much celebration in England, giving rise to a number of commemorative names including Portobello Road in London.

Vernon took Porto Bello with just six ships

Vernon took Porto Bello with just six ships.

‘N

EVER A STRUGGLE MORE MARVELLOUS OR MORE CLOSELY CONTESTED

’

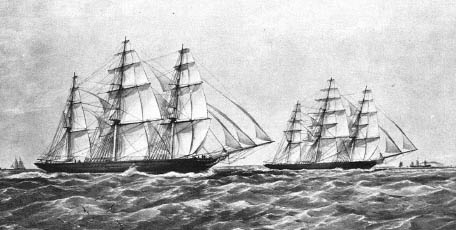

In the nineteenth century a sailing ship of great beauty, grace and speed evolved – the clipper. Carrying a very large spread of sails on three or more masts, these were the greyhounds of the sea and ideally suited for high-value, low-bulk cargoes such as China tea. They achieved record-breaking sailing times, often in spectacular races with other clippers to be the first to land their cargo.

The Great Tea Race of 1866 was a nail-biting event from start to finish. In the spring nine clippers assembled at the Pagoda Anchorage of the Min River at Foochow, jostling to take on board the new season tea as quickly as possible. The first vessel to unload the precious cargo in London could claim an extra ten shillings a ton in freight charges. Huge sums of money were bet on the outcome of the race, and English tea merchants in Mincing Lane were ready to begin bidding the moment they tasted samples of the sought-after first tea of the season from the fastest clipper.

Its 24,000-km route took the ships across the South China Sea, through the Sunda Strait of Indonesia, across the Indian Ocean, round the Cape of Good Hope and up the Atlantic Ocean to the English Channel. The five leading vessels were often in sight of each other, passing and repassing as they knifed through the waves.

The race generated great excitement as the fastest vessels entered British waters virtually neck and neck. The

Daily Telegraph

of 12 September reported: ‘A struggle more closely contested or more marvellous… has probably never before been witnessed.

Taeping

… arrived at the Lizard in the same hour as

Ariel

, her nearest rival, and then dashed up the Channel, the two ships abreast of each other. During the entire day they gallantly ran side by side, carried on by a strong westerly wind, every stitch of canvas set, and the sea sweeping their decks as they careered before the gale.’

Taeping

, carrying 695 metric tons of tea, won the race by a whisker, taking 99 days to sail to London and docking just half an hour ahead of

Ariel

. In the spirit of sportsmanship the two ships’ owners split the winner’s premium.

Taeping

Taepingand

Ariel.

AT CLOSE QUARTERS – at close range.

DERIVATION

: in the seventeenth century hand-to-hand fights when ships were boarded by the enemy were known as ‘close-fight’ engagements, and the term was also applied to the barriers the sailors erected to keep assailants at bay. By the mid-eighteenth century this confined defensive space had come to be known as ‘close quarters’.

I

IT’S NOT A ROCK, IT’S A SHIP

!

In January 1804 the Royal Navy took possession of a rock, 180 m high, 1.6 km off Martinique, the centre of French power in the Caribbean – and then declared the barren pinnacle a warship. This uninhabited islet was an ideal site for establishing a blockade as it dominated the approach to Port Royal, the capital of Martinique. And, with a visibility of 64 km from the summit, a signal station could be set up to pass on intelligence about French ship movements.

However, there were a large number of obstacles to be overcome. The only landing spot was on the western side; heavy swells and narrow rock ledges made any attempt to do so very chancy; and there was no food or water on the island.

Commodore Samuel Hood had reconnoitred the rock in his flagship HMS

Centaur

and was well aware of the challenges it posed. Fortunately his first lieutenant, James Maurice, was an amateur mountaineer and he went ashore and found a route up the sheer rock face.

A working party with several weeks’ provisions was landed. They found dry caves where they set up operations. With the aid of pitons and ropes the nimble seamen, used to swarming up rigging, scaled the heights and installed rope ladders. One hazard they had not bargained on, however, was the deadly local snake, the

fer-de-lance

.

Eventually the defences of Diamond Rock comprised two 24-pounders just above sea level, a 24-pounder halfway up and two 18-pounder cannon right on top. Getting these massive weapons in place was a heroic undertaking which took long backbreaking days at the capstan. After a line was run ashore a cable was rigged from the mainmast of the anchored

Centaur

to the top of the cliff, and the big guns were painstakingly hauled to the rock using an ingenious sling. Then began the formidable task of landing water and provisions for 120 men.

Maurice was installed ashore as commander, and in front of the assembled sailors and marines he proudly read out his commission. A pennant was run up and Diamond Rock was officially rated a sloop of war.

An artist, John Eckstein, obtained Hood’s permission to record for posterity one of the most outstanding achievements of the age of sail. He painted a series of aquatints which were published in 1805. Eckstein was amazed at the ingenuity of Jack Tar and said, ‘I shall never more take my hat off for anything less than a British seaman.’

For a year and a half the British fired at any passing French ship and proved such a thorn in the side of Admiral Villeneuve on his way to his destiny at Trafalgar that he eventually threw his entire battle fleet at the rock. On 2 June 1805 Captain James Maurice surrendered. It was not French firepower that defeated him, however, but an earth tremor which cracked the water cistern he had installed.

In the Royal Navy, there was (and is to this day) an automatic court of enquiry if a captain lost his ship, whatever the reason. This rule applied even if the ship was a rock, so a court was convened aboard HMS

Circe

on 24 June. It did not take long to reach the verdict that Maurice and his officers had done everything in their power to the very last in the defence of the rock and against a most superior force.

HE SEA WOLF

’

Thomas Cochrane was one of the most daring and successful captains of the Napoleonic wars, called ‘

le loup des mers

’, the sea wolf, by Napoleon Bonaparte. In the course of his career he captured 50 enemy ships in just one year, was dismissed from the Royal Navy for alleged fraud, commanded the navies of Chile, Brazil and Greece, and was eventually reinstated in the Royal Navy as an admiral. He was a radical politician, an early advocate of many technological innovations that were later adopted by the navy and the inspiration for a number of fiction writers.

But in many ways Cochrane was his own worst enemy and made several powerful foes, especially in his political campaign against corruption in the navy. Earl St Vincent, although sympathetic to some of Cochrane’s

beliefs

, said of him that he was ‘mad, romantic, money-getting and not truth telling’.

One of Cochrane’s most famous exploits occurred on 6 May 1801 when he took the 32-gun Spanish frigate

El Gamo

and its crew of 300. His vessel, the 14-gun brig-sloop HMS

Speedy

, had a crew of just 50. On spotting

El Gamo

Cochrane hoisted the Stars and Stripes (whose country Spain was not at war with) and sailed directly towards her. When he drew close he lowered this flag, hoisted the Union Jack and began firing. His first salvo killed the Spanish captain. Cochrane stormed the ship with a boarding party which included his entire crew, except the ship’s surgeon who was left in charge of the wheel. A ferocious fight with cutlasses, axes and pikes ensued. At one point Cochrane called loudly for another 50 (fictitious) reinforcements to follow – and the Spanish surrendered.

But the plucky little ship’s luck did not last and

Speedy

was later taken by the French, who gave her to the Pope renamed

San Paulo

.