Stonehenge a New Understanding (19 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Our faunal specialists, Umberto Albarella and Sarah Viner, have much more data to work with. Umberto has gone through the 1967 finds and discovered that most of the young pigs were killed at around nine months old. He can tell this by measuring the growth and wear on the teeth within the mandible. Reckoning that, like today, pigs farrowed only once a year in Britain’s temperate climate (during the spring), Umberto has deduced that since the young pigs were killed at nine months, they were therefore killed in midwinter. To his surprise, when examining the faunal remains, he found the tips of flint arrows embedded in pig bones: At least some of these animals were shot with arrows.

12

Then the pigs were barbecued or roasted—the ends of many of their limb bones were scorched by flames while the meat was cooking.

Such arrow injuries might be expected were the pigs in question wild boar, but there wasn’t a single wild pig among the 1967 bones—all were

domesticates. Umberto knows that in some parts of the world—New Guinea, for example—domestic pigs are shot with arrows at point-blank range when a tribe or village is putting on a feast. His results don’t tally with this possible scenario, however, because the wounds on the Durrington pigs are located in all parts of the skeleton, including the limbs and feet. This suggests that perhaps these pigs were shot from a distance. Maybe archers demonstrated their skills by bringing down squealing ranks of porkers in front of a crowd ready and eager for a huge pig-roast.

There is another curious feature of the animal-bone remains. None of the animals was very young—no piglets and no calves. Umberto and Sarah have looked at animal bones from many different places and periods, and know that bones of newborns are frequent finds in prehistoric settlements. Such very young animals are not only more likely to die of natural causes, but also provide tender meat—in the form of suckling pig, for instance. This absence of newborns (or neonates) can only mean that there was no year-round stock-breeding at Durrington Walls. The animals were brought in already grown and did not give birth here. This was a “consumption site,” a place for eating but not for raising animals.

Isotopic analysis of the animals’ teeth can confirm this and tell us where the livestock might have come from. Together with isotope scientist Jane Evans, Sarah and Umberto have tested the teeth in 175 cattle mandibles.

13

Given that Durrington Walls and Stonehenge are surrounded by chalkland in every direction for at least twenty miles, they expected the cattle to have values consistent with their having been reared on chalk soils.

The results are fascinating. Very few of these animals had lived on chalk and the others lived fairly eventful lives—for cows. Some were reared in the far west, either in Devon and Cornwall, or in west Wales. The others were from the lowlands, either west of Wessex or to its east. By slicing the tooth enamel more finely, Jane tracked their movements as young animals. Many had different histories, coming from different herds.

A similar picture is emerging with the enamel on the pigs’ teeth. Although we initially thought that pig-tooth enamel is not strong enough to have remained uncontaminated by the chalk soil in which the animal

remains lay, researcher Richard Madgwick, working at Cardiff University, found that some of the Durrington pigs were also raised off the chalklands. Herding pigs is never an easy business, but these had traveled at least twenty miles to Durrington.

The results so far have been so unexpected and so revealing that we’ve started a project to look at more of the pig teeth, and the results should be available in a couple of years’ time. In the meantime, we can conclude that the Durrington Walls village was the hub of a network that stretched across southern Britain to provide supplies to feed an army-sized population, possibly bringing some animals from as far away as Scotland. The inhabitants of Durrington Walls would have required huge quantities of resources: antler picks to dig the holes, massive tree trunks for building the timber circles, as well as wood and reed thatch for their houses, ropes for maneuvering timber posts into position, flint for tools, clay for making pots, reeds and withies for making baskets, skins for making bags, and meat and vegetables to feed everyone.

Some of these could be found locally. Reeds grew in beds along the river, clay could also be found along the river margins, and ropes were made out of linden bast, honeysuckle, or twisted animal hides. Local flint mines north of the henge provided nodules of top-quality flint, but other items had to come from further away. Red deer were more numerous in Neolithic Britain than they are today, but the number of antler picks required must have been in the thousands. The vast majority were naturally shed—red deer lose their antlers in spring—and would have been collected from the hills where the deer roamed.

We know that there was a certain amount of woodland in the Avon valley at the time that Durrington Walls was inhabited,

14

but not the huge numbers of tall, mature trees needed to build the timber circles. These grew in canopy woodland where dense stands of oak, elm, ash, and linden competed for light by growing long, straight trunks that branched out only toward their tops. Such woodland would have been found to the north, in the Vale of Pewsey, or further south along the Avon valley. Most of the larger trees must have been brought from at least ten miles away, whether floated down the river or hauled overland.

While pork, beef, and dairy products provided animal protein, the Durrington population also ate a variety of vegetable crops. Prehistoric

plant remains can survive for thousands of years but are hard to recover; they survive only in heavily waterlogged places (where they haven’t been able to rot) or if they were charred by fire in prehistory. Such remains are usually too small and fragile for the digger to retrieve directly from the soil. They are usually found by “flotation”: Like the wet-sieving for small artifacts and bone fragments, soil samples are washed through sieves (with very fine mesh sizes of 1 millimeter and 300 microns) to catch seeds and other fragments.

Ellen Simmons, the project’s specialist in carbonized plant remains (paleoethnobotany), has found burned fragments of apples, hazelnuts, and tubers on the Durrington house floors and in the yards. The apples would have been small and sour—more of a crab apple than a Cox’s Orange Pippin—perhaps best used for making cider. Hazelnuts are found in virtually all Neolithic settlements; they were evidently a dietary staple and might well have been managed in coppiced woodlands as an autumnal crop. Various wild plants, such as pignut, silverweed, dandelion, and burdock, have edible tubers and would have been easily collectible and relatively simple to store and transport.

15

Ellen has also discovered the burned remains of a starchy “cake,” probably made from crushed fruits of wild species, such as hawthorn.

Ellen found burned grains of wheat within the village. They are from southwest of the avenue; none are from the house floors or yard surfaces on the northeast side of the avenue. Does this restricted distribution of cereal remains mean that wheat was hardly used at Durrington Walls?

More than twenty years ago, archaeologists noted that many Neolithic sites in Britain had much more evidence for wild-plant use than for domesticated cereals.

16

They concluded that cereals were not common and, in this period, people still mostly relied upon wild-plant foods, just as their hunter-gatherer forebears had. Other archaeologists then pointed out that this was all to do with bias of recovery: Hazelnut shells are very likely to have been thrown in the fire, with some of them becoming carbonized, but cereals get burned only by accident. So it is only in extraordinary circumstances that we find carbonized prehistoric cereal grains. The state of knowledge at present is that well over a hundred

Neolithic sites in Britain have now yielded carbonized cereal remains, so they are not as rare as previously thought.

17

The rarity of such crop remains on a site such as Durrington Walls that has been so carefully sampled, with thousands of liters of soil sent off for flotation, is still not unusual compared with other Neolithic settlements. It probably reflects the poor survival of cereals (with few of the precious grains ending up burned on the fire) for the archaeologist to find. Cereals might well have been more common at this village than appears to be the case.

Another ticklish question concerns the tools that were used at the Durrington settlement. Among eighty thousand worked flints, Ben Chan, the project’s flint specialist, has found just one small fragment of a flint ax. The 1967 team found fragments of just two among almost ten thousand Neolithic worked flints.

18

By comparison with other Neolithic sites with similar quantities of worked flints, there should have been at least sixty axes and ax fragments. There was plenty of carpentry going on at Durrington but there’s no visible trace of the axes used to chop and shape the timbers for either houses or post circles. Were axes and their broken fragments carefully collected up and dumped elsewhere? Or were axes used only by people living in other parts of the settlement not yet excavated? Neither of these explanations is at all convincing. There are three pieces of circumstantial evidence that this Stone Age culture had in fact got hold of some new technology.

When people were living at Durrington Walls, copper had already been in use in eastern Europe for thousands of years, since about 5500 BC. That part of Europe has a distinct Copper Age (the Chalcolithic) between the Neolithic and Bronze Age.

19

It has been generally thought that ancient Britons changed from using stone to using bronze without a noticeable intermediate stage, though archaeologists now speak of a brief Copper Age (or Chalcolithic) in Britain between 2500 and 2200 BC.

It took an exceedingly long time for copper metallurgy to spread across Europe. By 3200 BC it had only got as far as the Alps: the man nicknamed Ötzi the Iceman by his finders, who ended up frozen into a high-altitude glacier, had a copper ax. Mysteriously, copper metallurgy then apparently took about seven hundred years to spread as far as Britain. That is painfully slow progress, only about a mile a year.

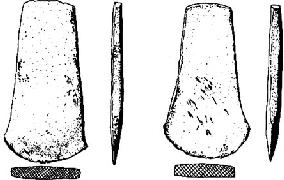

Copper axheads from Castletown Roche in Ireland. These are similar to the earliest metal axes used in Britain.

The earliest copper in Britain is found in Beaker burials, a new burial rite that appeared around 2400 BC, and many archaeologists have assumed that copper was introduced by these immigrant Beaker people, who found out after their arrival how rich in deposits of copper ore Britain and Ireland actually were. But perhaps copper tools were already in use before the Beaker immigrants arrived. Copper must have been very valuable at first, so it is unlikely that people would have casually let it fall into the kinds of places where archaeologists would find it. Copper tools would have been both highly prized and recyclable, so there’s no reason why they should have ended up in the ground.

Archaeologists have often wondered whether copper axes were actually of much use. They are very pretty, shiny objects, but were they any good for practical tasks, such as chopping down trees? Unless copper is mixed with tin to form bronze (which doesn’t seem to have happened in Britain until about 2200 BC), it’s quite soft and its edge blunts easily. Perhaps copper axes and other objects were symbolic items, more like jewelry than tools, made to impress rather than to be used.

One of the documentary crews filming our excavations around Stonehenge decided to find out. They gave Phil Harding,

Time Team

’s well-known local archaeologist, a hafted copper ax and a medium-sized tree to chop down. Phil had often used flint axes for felling trees and was suspicious that the copper ax wouldn’t be anywhere nearly as good. To his surprise, not only was it easier to use than its flint counterpart, being lighter, but it also cut more quickly. Stone axes have to chop with oblique

strokes so the axman’s cut into the tree is very broad, resembling the chewing of a beaver. Copper axes can be used to cut at a more perpendicular angle. You just have to stop every now and again to hammer out the blunted edge.

Archaeologists can get very hot and bothered about exactly when copper metallurgy started in Britain, and there has been a reluctance by some to see it pushed back any earlier than 2400 BC, or fifty years earlier at most. There are few hard facts, but some circumstantial evidence now suggests that the use of copper in Britain does go back to before the arrival of the Beaker people. When we dug into Durrington’s henge bank, we discovered that, while some of the chalk from digging the ditch bears the marks of antler picks, two chalk blocks have long thin, V-shaped cuts into them, as if made by the chopping motion of an ax. Yet the cuts are too thin to have been formed by a stone ax. It seems likely that only a metal ax could have produced such a thin groove. We can date the ditch-digging to 2480–2460 BC, giving us a clue that someone was using a copper ax slightly earlier than expected.

20