Stonehenge a New Understanding (7 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

In any archaeological project, excavation is the quickest and easiest part of the process; the post-excavation work on finds and plans takes years to complete, often without any funding or dedicated research time. In his later years, Atkinson was distracted from writing up his excavations by administrative duties and illness. He died in 1994, and it seems that little in the way of excavation records was found when his papers were cleared out. Atkinson’s students remember him saying that everything was in his head and today no one knows what records he kept of his

fieldwork. Stuart Piggott certainly put some things down on paper: He was an accomplished draftsman and drew many of the plans and sections during Atkinson’s excavations.

In 1956, Atkinson published his book on Stonehenge, describing the monument in detail and setting out what seemed to be a likely sequence in which it was built.

20

He worked out that the first phase of construction was the circular bank and ditch, and the ring of pits called Aubrey Holes. Then, he thought, a semicircular arc of bluestones was added. This was followed by the erection of a circle of upright sarsens, all joined together by lintels, and the trilithons inside the circle (with the bluestones being rearranged, also inside the sarsen circle).

At the time Atkinson was writing, radiocarbon dating was in its infancy, so he had no real dates to work with, and his estimation of when Stonehenge was built was out by quite a bit. We know now that most of it was built during the Neolithic but Atkinson thought that it must have been constructed during the Bronze Age (that is, the second millennium BC), the period after the Neolithic when metals were first introduced to Britain. Because Atkinson thought Stonehenge belonged to the Bronze Age, he thought it might have been built by an architect from ancient Greece—where a civilization was flourishing at Mycenae during the Bronze Age.

For the remainder of the twentieth century no excavations were carried out at or around Stonehenge except in advance of developments, such as the car park, the visitor center, road improvements, cable trenches, and the visitor footpath. The most productive of these small investigations was Mike Pitts’s excavation in 1980 of a cable trench along the road immediately outside Stonehenge’s northeast entrance.

21

Mike was curator of Avebury Museum at the time, and had to step in very swiftly when he realized that no one in authority had made any provision for archaeological work in advance of the Post Office laying new cables. During this excavation, Mike discovered that the Heel Stone was once one of a pair of stones.

h

He found the hole for a second stone (Stonehole 97) next to it, and this hole was dug into the soil that had filled an even larger hole.

22

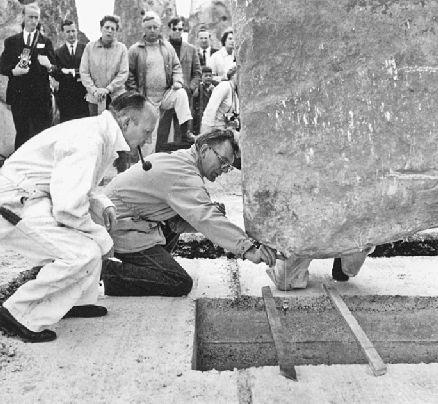

Professor Richard Atkinson (kneeling center) supervising the re-erection of Stone 23 at Stonehenge in 1964; Professor Stuart Piggott is standing fourth from the left.

For a while, archaeologists speculated that the Heel Stone and this previously unknown, vanished stone had formed a “gunsight” for prehistoric worshippers looking down the Stonehenge Avenue: They would have seen the sun rise between the two stones at the midsummer solstice. This idea turned out not to work particularly well. The new stonehole is slightly offset from the Heel Stone so that the pair was not perpendicular to the line of the avenue. Its position is more convincingly explained as being the end of a row of equally spaced stones

i

within the entrance and leading out from the Slaughter Stone.

As for the large pit that Mike Pitts found beneath Stonehole 97, Atkinson had seen the southern part of this same feature during his excavation of the Heel Stone ditch in 1956. This pit was more than five meters long, and Mike wondered if it was actually the natural hollow left by the removal of a very large stone. Perhaps a sarsen had lain here until it was discovered and erected in Stonehole 97 by Neolithic people? This stone might then have been moved to a new position, set within its own circular ditch—the sarsen now called the Heel Stone.

23

Mike Pitts’s cable-trench dig also revealed masses of sarsen chippings in this area outside Stonehenge’s entrance. Hawley had also found a large dump of them near the Heel Stone. These areas outside Stonehenge seem to contain greater quantities of sarsen chippings than do the areas that have been excavated inside. In contrast, Atkinson and other excavators working within Stonehenge’s interior had found many more Welsh bluestone chippings than Mike found outside Stonehenge. Stone chippings show where a stone has been “dressed” (worked into shape). The distribution of the chippings shows that the bluestones were dressed inside the circle at some point in time, and that the sarsens were worked outside the ditch and bank.

In the 1980s, English Heritage (the government body responsible for archaeology in England—today’s successor to the old Ministry of Works) commissioned a local commercial archaeology company, Wessex Archaeology, to employ a team of young specialists to make sense of Hawley’s and Atkinson’s excavation records and publish the results as a definitive book on the archaeology of Stonehenge. Although it received little help from either Atkinson or Piggott, this team, led by Ros Cleal (now curator of Avebury Museum), produced in 1995 an authoritative but necessarily second-hand account of the twentieth-century excavations.

24

What makes this report particularly important is that it includes the results of a carefully planned program of radiocarbon dating and statistical analysis, in which certain finds from the old excavations were dated to establish Stonehenge’s different phases of use.

The only way we can date Stonehenge is by using radiocarbon dates obtained from items of organic material that were deposited there when it was being built and rebuilt—for our generation of archaeologists, there is no way to accurately date a stone (but who knows what

techniques will be developed in the future). The stones at Stonehenge have been moved about and reerected many times. Stonehenge is full of pits where stones once stood; the stones themselves have since vanished, either shifted to a different spot or removed completely. These pits, called stoneholes, and the ditch around the stone circle, contain the dating evidence.

The ditch that encircles the standing stones has been the easiest thing to date, as more than twenty antler picks were left on the bottom of the ditch by the Neolithic workers who dug it out. Dated together, and taking into account dates from articulated animal bones from higher up in the soil that fills the ditch, these antler pickaxes from the ditch produced a combined date now refined to 3000–2920 cal BC (calibrated years Before Christ)

j

at 94.5 percent probability. Thus, the Stonehenge ditch was dug out at some point during this eighty-year period within the thirtieth century BC, when people in Britain had already been farming for a thousand years. The ditch then started to silt up, becoming filled in during the period 2560–2140 cal BC.

Compared to dating the various arrangements of standing stones, dating the Stonehenge ditch was easy for Cleal’s team. Richard Atkinson’s excavations in the center, building on Hawley’s discoveries, revealed a semicircular double arc of holes for bluestones that once stood near the center of the stone circle. Atkinson named these the Q and R Holes, and he thought that the bluestones that once stood in them must have been in position before the large sarsens were erected. He excavated more than twenty of these Q and R Holes, but sadly no antler picks (pickaxes) were found.

In the outer circle of large sarsens, one stonehole excavated by Hawley did have an antler pick in a layer of chalk rubble that had once been packed around the stone. This pick produced a date of 2640–2485 cal BC. More antler picks came from around the sarsen trilithons that stood within the sarsen circle, enclosed by it. The dates for these varied from 2850–2400 cal BC to 2470–2200 cal BC. Since a layer must always be dated by the latest artifact left in it, the date for the trilithons is apparently more

recent than the date for the outer circle of stones. It seemed as if the trilithons were erected more than a century

after

the outer circle. These were the dates that Ros Cleal’s team had to work with. It all depended on whether Atkinson and Hawley were right about the layers in which they found the antlers and hadn’t made any mistakes interpreting the complex stratigraphy, in which pits frequently intercut each other.

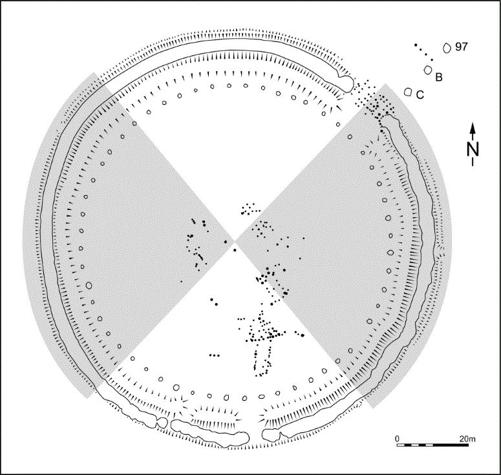

Schematic plan of astronomical alignments at Stonehenge—Stage 1 (3000–2920 BCE). The post settings in the northeast entrance were aligned approximately on the northern major moonrise; Stone 97 provided a sightline from the center of the circle to the midsummer solstice sunrise. Together with Stones B and C, it provided an approximate alignment on the northern major moonrise. Some of the post settings in the center of the circular enclosure were aligned approximately on the southern major moonrise to the southeast. The area shaded gray shows the range of moonrise (east) and moonset (west) at major standstill.

Ros’s team did a good job of making sense of it all—the pits, the stones, the perpetual rearrangements. Using all the old excavation records they could find, together with the new radiocarbon dates, they worked out a new chronological sequence for Stonehenge’s use. There were still some anomalies but it seemed it was the best that could be done on the available evidence. At the time English Heritage were pulling together this big report, it seemed highly unlikely that anyone was going to be digging at Stonehenge to get any new dating evidence. To put things in context, the report was being prepared during a period when Stonehenge was at the center of real conflict—the country was in the midst of what sociologists call a “moral panic” about the New Age Travelers’ movement, and Stonehenge had been the scene of violent confrontations between the police and the Travelers’ “peace convoy.” Potentially contentious excavations were not on the agenda.

In general, archaeologists accepted that the Stonehenge radiocarbon dates just had to be right, but this left a big problem in the construction sequence. How could the builders have put up the trilithons in the center of Stonehenge if the outer sarsen circle was already in position? There simply isn’t enough room. Perhaps the outer circle was never finished—with a big gap in the outer ring, it would have just been possible to maneuver the inner stones into position. This was a real puzzle for archaeology, as the sequence didn’t seem to make sense. Perhaps the dates were misleading—maybe some of them came from extremely old antler picks that had been antiques when they were buried? It was not until years later that the mystery was unraveled.

Ros Cleal and her team were careful to present the facts—accurate plans and detailed descriptions. It would be left to others to mull over the astronomical orientations and opportunities that Stonehenge presented. Ever since William Stukeley noted Stonehenge’s orientation toward the midsummer solstice sunrise,

k

there has been fascination with Stonehenge’s astronomical possibilities.

25

At the end of the nineteenth century, the astronomer Norman Lockyer attempted unsuccessfully to

date Stonehenge on the basis of its solstice orientation: Slow changes in the tilt of the earth’s axis cause the sun’s cyclical movement to change very slightly over time (about one seventieth of a degree every hundred years). It was not until the 1950s and 1960s, however, that astronomy came to play a dominant role in many new interpretations of Stonehenge.

In 1963 an American astronomer, Gerald Hawkins, shook the archaeological establishment by proposing that Stonehenge was used not just as a complex calendar but also as a predictor of solar and lunar eclipses.

26

His claims ushered in a new era of regarding Stonehenge as something more than a temple of the sun—an idea that had been current for over two hundred years, ever since William Stukeley had declared it a druid temple. Hawkins’s bestseller,

Stonehenge Decoded

, was published in 1965 and was read by a public in awe of the newly invented computer, an important tool in his investigation.