Stories for Boys: A Memoir (21 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

As we were driving out of town, I felt a migraine coming on. A silvery aura appeared in the center of my field of vision, and I knew from experience that I had about fifteen minutes before the knife blade would sink into my temple. I had to turn my head to see where I was going. I only had peripheral vision. I pulled over to the shoulder of the interstate off ramp. Christine came around to drive, and I went around to the passenger seat.

Migraines paid me a visit five or six times a year, always at the release of some tension. After something I’d been worried about for a long time had come to an end, the silvery aura reliably presented itself. A few different times I’d gotten a prescription for migraine medication, but I’d never filled it. There was something I savored about settling into durable, predictable, and thought-numbing pain. A good migraine meant that I could stop tormenting myself with my own thoughts and imagination and endless speculation, my own smoldering judgment and confusion. My migraine was like a three-hour existential hall pass from the interminable class that was myself.

Remembering Remembering

SOMETIMES EVAN SAYS, “REMEMBER WHEN WE VISITED your old house, Dad? Remember when we walked around the block and you showed us where your friends lived and that park where you played? Remember that place on the walk to your school where you jumped from one wall to the other? Remember when we walked around in your old school and the lady came out and you said, ‘I used to go to school here.’? Remember that?”

Now I can’t remember my old neighborhood without remembering my children walking with me through my old neighborhood, holding my hand or with their arms swinging at their sides. I can’t remember my old neighborhood without remembering Evan remembering my neighborhood.

VLADIMIR NABOKOV, IN

Speak, Memory: an Autobiography Revisited

, writes,

Speak, Memory: an Autobiography Revisited

, writes,

I confess I do not believe in time. I like to fold my magic carpet after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another. Let visitors trip. And the highest enjoyment of timelessness – in a landscape selected at random – is when I stand among rare butterflies…

Mysteries

I’M REMEMBERING MY MOTHER AND father sitting in the living room of my childhood home. They’re reading in their separate chairs. I am nine years old.

My mom is reading a Dick Francis horse-racing mystery. She has already read, several times, all twenty of Dick Francis’s horse-racing mysteries published up to that point, 1980. She buys them in hardcover, right when they’re published. Re-reading these mysteries does not require any willful forgetting on my mother’s part. No denial whatsoever. She can never remember who did what to whom. It’s a mystery every time. She loves this about her memory. It has ceased to astonish her. She gets to re-read the books she loves over and over. It takes about a year before she can confidently re-read a book with the satisfactory amount of amnesia, so that the book is pleasantly familiar, but surprising. My father is reading a science fiction novel. He is far away, on a cold planet in a remote solar system, a mining colony, an outpost in galactic Siberia. My parents’ appetite for reading is sensual; like a pheromone it fills the house. Has a day ever passed in our home when I do not see them reading? I can’t remember. I don’t think so. Our house is so often this quiet and calm; we are all reading, somewhere, if not together in this room. It is summer, evening, bedtime a long way off. The hour of lamps.

There is nothing I want to do more than read in this quiet living room with my mother and father. Nothing is calling me away. I am happy. I am reading a Hardy Boys mystery on the brown shag carpet. I’m just out of my parents’ sight, in that narrow four foot space on the other side of the green sofa, beside the dark, walnut built-in bookshelf that runs the length of the room. My brother Chris and I own all fifty-eight books of the original Hardy Boys mysteries – all the blue hardbacks, every single one – organized by number along the bottom of the bookshelf. The desire to read is my oldest, strongest desire. Chris could read very early, at three or four. He is a year and a half older, and he loves reading as much as my parents. He is always reading. In the room we share, our twin beds are against opposite walls, and now I am remembering staring at my brother in the dark. Chris is reading a Hardy Boys mystery by the light of the streetlamp through our open-curtained windows. I cannot read yet because in this memory I am five, but I have a Hardy Boys mystery in bed with me anyway. I am studying the pictures for clues, pretending to read, claiming to read. I am burning with impatience and desire. I remember. I want so badly for the words to announce themselves. But soon I am nine and I am Joe Hardy, the younger brother, and I am on the case. My father, the detective Fenton Hardy, has disappeared yet again, and Frank and I must find him, and solve the mystery.

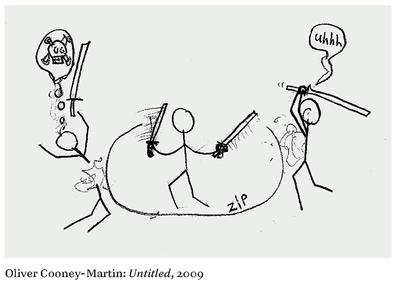

I am remembering now how happy I was then, that calm, quiet happiness, so still and focused, a happiness outside of time, a happiness I so often see in Oliver, who is always reading, every single day, morning, afternoon, evening. Now he’s reading the Usagi Yojimbo series, graphic novels by Stan Sakai, about the adventures of a samurai rabbit.

SEVENTEEN BOOKS FROM this series are stacked right now in two neat piles on our coffee table in the living room. Oliver has read them all and started over. We need to go to the library for more.

Master of None

MY FATHER WAS A SEVENTH-GRADE P.E TEACHER. HE drove all over the Midwest selling pharmaceuticals for Squibb. He sold real estate for Century 21. He sold gasohol, an alternative gasoline and alcohol fuel mixture, for the National Gasohol Commission. He weatherized houses. He worked in a hardware store, in the nuts and bolts area; he was promoted to kitchen design. He went back to school in his fifties, earning an undergraduate and master’s degree in speech pathology. He learned sign language and worked at a school for the deaf. He took a job in a nursing home helping elderly men and women who had suffered strokes regain the ability to speak. After harrowing, life-altering setbacks, patients looked to my father to help them recover their voice.

In other words, after more than thirty years of catch-as-catch-can employment, my father found his calling. I have never seen my father at work with his patients, but it’s easy for me to imagine him: patient, kind, gentle, encouraging.

Everywhere my family moved, because of my mother’s career in academics, in government, and finally in administration at three universities in three different states, my father found a new job. Each move left him out of work, sometimes for months at a time. If he was discouraged, disheartened, depressed, I did not know it. When I was in middle school and high school, I was often embarrassed by him, by his presence, his availability. I felt the need to explain why, always, my father picked me up from school, drove me to and from practice in his old white Chrysler Newport. When I think of my embarrassment now, I wince with shame. I have to remind myself that there was no such thing then as stay-at-home dads. It was a different time.

I can still remember coming out the front doors of middle school and seeing the big white Chrysler parked alongside the curb, my father behind the wheel reading a paperback. More than once, I kept my eyes straight ahead and walked right past him. I walked the two miles home. He pulled into the driveway fifteen or twenty minutes later and came in the house wondering what had happened. I said that I hadn’t seen him. He did not challenge my lie.

MY LOVE FOR my mother was then, and still is, unambivalent. We spend time together easily. When I was growing up, I liked to go grocery shopping with her, just for her company. We watched old movies together on weekends, Westerns and Mysteries, especially. For my encyclopedic knowledge of Alfred Hitchcock and Cary Grant, of Katherine Hepburn and Paul Newman, I have my mother to thank. My mother loved, and still loves, college football and basketball. We attended games together on campus. We watched games together on television, shouted the same encouragement and advice at the coaches on the screen. We played, and still play, pinochle and cribbage with an intensity that Christine finds unsettling. My mother told me that I could do whatever I set my mind to do. She taught me to work hard, to pick myself up and dust myself off when I failed, and try again. She instilled in me a lifelong belief in myself. But it’s also true that my mother worked hours as hard and long as the fathers of most of my friends growing up. Harder. Longer. As a woman professional in the 1970s and 80s in the all-male field of economics, she had to be better than, not just as good as, the men she worked with, taught with, published alongside.

WHEN MY FATHER was a teenager, he drove his father around from bar to bar on Saturdays. They started around nine in the morning. They kept going until my father’s father was too drunk to walk. All day, my father would wait in the car, parked outside on the curb, and read a paperback. Late in the afternoon or in early evening, he’d deliver his father safely home, stinking drunk. Then he’d have the car that night to go out with his friends or out on a date with a girl.

MY FATHER DID not play sports well. He’d been cut from his high school football team. But he threw countless balls to me and caught countless balls in return. He rebounded countless shots. My father took me to cub scout meetings, to webelos and boy scout meetings. He had been an Explorer Scout himself and so was undaunted by the task of whittling a car from a wooden block and then painting and racing it, with its lead weights, down a varnished ramp. He took me camping. He took me out into the woods along the Platte River to cut wood for our fireplace for winter. Each November, I helped him make candles for Christmas presents, pouring the hot, colored wax into molds, in his shop in the basement. He’d never taken a lesson, but he taught me to play the piano and the guitar.

Other books

Witchlanders by Lena Coakley

Razor by Ronin Winters

Tales From the Black Chamber by Walsh, Bill;

Tritium Gambit (Max and Miranda Book 1) by Hyrkas, Erik

Hells Gate: Santino by Crymsyn Hart

Shadow Play by Frances Fyfield

At Face Value by Franklin, Emily

Be With You by Scarlett Madison

American Gods by Neil Gaiman

In The Wake by Per Petterson