Stories for Boys: A Memoir (17 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

I knew exactly how Evan felt.

DURING THE ENDLESS summer of the Cooney-Martin kitchen remodel, our small 1970s white refrigerator, which came with the house when we bought it, was relocated to the living room, along with the kitchen table and the microwave. Evan liked this. It was like camping in your own living room, with your own refrigerator. But then one day when he came home from a friend’s house, there was a brand spanking new, stainless steel Whirlpool Gold, Energy-Star, bottom drawer freezer refrigerator in the kitchen, and the old white refrigerator was out by the curb. Evan struggled with this. He howled. He held a vigil, lasting into the dark of evening and past bedtime, out on the curb beside the old refrigerator. He crumpled the “Free” sign Christine had taped on the refrigerator and threw the ball of paper in the middle of the street.

The next morning, Evan woke up and went outside and sat beside the refrigerator in his yellow SpongeBob pajamas. He brought out his collapsible Buzz Lightyear lawn chair and set it on the sidewalk. It was a sit-in, a non-violent protest that could only make his mother proud, even though she hated the old white refrigerator, which I thought was perfectly fine. She loved her new stainless steel refrigerator more, at that particular time and perhaps still, than she loved me.

People passing by slowly in their cars stopped to look at the old white, beloved refrigerator.

“Hi there,” they said sweetly to Evan. “Are you giving away your refrigerator?”

“No!” Evan snarled. “You can’t have it.”

The people drove away.

Mark walked over. He had a daughter in high school and was unmoved by Evan’s unhappiness. He wanted the refrigerator. He could come get it right now. He had his own handtruck but rarely had such a fine occasion to put it to use. He could just wheel the refrigerator down the street. Evan watched this conversation transpire with growing disbelief.

“Hey, Evan,” I said. “Mark ’s the one who gave us the yellow slide for the treehouse.”

Tears were streaming down Evan’s face. He hopped up and down. His whole face turned red. He was crying his hardest, giving his full effort, which is all you can really ask for.

Mark said, “Evan. Wait. Stop. Listen. I have a deal for you.” He had to say this a few times before Evan could hear over the tantrum he was throwing. Finally Evan stopped, his fists balled at his sides.

“What if,” Mark said, “I just

borrow

the refrigerator from you, since you don’t have room for it anymore. I’ll borrow it and keep it in my garage. And that way I can put beer and soda and stuff in there for me, but I’ll always keep a few juice boxes in there for you, and you can come down and visit your refriger - ator any time you want. You’ll just come over and say, ‘Hey, Mark, how is my refrigerator doing?’ And I’ll say, ‘Just great, Evan. You want a juice box? I’ve been keeping one cold for you?’ And then you can have one if your mom and dad say it’s okay. How does that sound?”

borrow

the refrigerator from you, since you don’t have room for it anymore. I’ll borrow it and keep it in my garage. And that way I can put beer and soda and stuff in there for me, but I’ll always keep a few juice boxes in there for you, and you can come down and visit your refriger - ator any time you want. You’ll just come over and say, ‘Hey, Mark, how is my refrigerator doing?’ And I’ll say, ‘Just great, Evan. You want a juice box? I’ve been keeping one cold for you?’ And then you can have one if your mom and dad say it’s okay. How does that sound?”

A smile slowly emerged on Evan’s face. This smile grew wider. Then Evan jumped up and raised his fist in victory. He shouted, “Yeah!”

Mark looked at me.

I said, “Sure.”

“I can come visit my refrigerator?” Evan said.

“Any time. And you can have a juice box when you visit,” Mark added. “You can come down for a juice box later today. It won’t take me long to get it all set up. Okay?”

“Okay,” Evan said. “Yes. Okay.” He wiped his tear-stained cheeks with the backs of his hands and wiped them on his shirt. He grinned mischievously. “Can my Dad have one of your beers?”

“He can, Evan. There’s gotta be some kind of game on. You could both come in for a while and watch TV.”

“Awesome,” Evan said. He wandered off to play with his toys. He didn’t even watch the refrigerator roll down the street.

Dear Oliver and Evan,

I know you’ve been worried for some time about Master. I have shared your concern. Please know that I’ve been keeping my eyes upon him, especially in the mornings before you and The Beloved One awake. Master is up so early that I don’t even need to urinate. Not badly, anyway. But I go out and urinate on the tree and the lilac bush, because I know that our routine helps Master feel better. I don’t scratch on the door to be let back in, because I know he does not like this. I wait. I am patient. Sometimes he forgets about me, and after a while, I whine, once, twice, not loudly, I do not bark, for I do not want to wake The Beloved One. Master hears and lets me in and we sit together in the dark of the morning time.

I wanted to tell you that I think Master is getting better. He has started to write on his laptop in the mornings, and this can only be for the good. I know The Beloved One shares this feeling. I heard her say this to the telephone when Master was away.

I will close now, but wanted to bring you these tidings.

Yours in deepest loyalty,

Rocky

Hypotheticals

IN THAT PBS DOCUMENTARY ON WALT WHITMAN, ED FOLSOM gets my vote for most valuable featured expert. He’s incredibly learned, but also completely engaged – Whitman’s life and troubles and poetry and journals are so alive to him, so crucial, relevant, contemporary. Folsom’s voice becomes trance-like, incantatory, he is so worked up about Whitman’s capacity to identify with complete strangers:

How do you come to care for people that you have never seen before and that you may never see again? Every day we encounter people, eyes make contact, we brush by people, physically come into contact with them, and may never see them again. But Whitman’s notebooks at this time are filled with images, just jottings, of these people, what they’re doing, what they look like, what their names are. ‘What is this person doing? What’s the activity that defines this person? If I were doing that activity that person would be me. If I were wandering the other way, rather than this way, that person could be me. That could be me. That could be me. What is it that separates any of us?’…That could be me. That could be me. That person could be me.

I’d been doing some hypothetical speculation, myself, on my father’s behalf. If only my father would have gone there or done that, he could have been … If he’d read

Leaves of Grass

when he was a young man … If he’d moved to Greenwich Village or San Francisco after high school instead of to an even more rural Virginia, to Blacksburg, a small town in the heart of Appalachia …

Leaves of Grass

when he was a young man … If he’d moved to Greenwich Village or San Francisco after high school instead of to an even more rural Virginia, to Blacksburg, a small town in the heart of Appalachia …

But Whitman never thinks this way. Whitman does not identify with complete strangers so that he can imagine a do-over. He identifies out of fascination and curiosity and empathy and the transcendental belief that our separation from one another is not nearly so distinct as it seems.

Whitman does not identify with the slave on the auction block out of sour grapes over his own fate. Whitman says, That could be me.

Whitman is as audacious as he is sincere as he is determined. With all people, of all races and ethnicities and sexual orientations and professions and heritages, in catalog after catalog in his long-lined, loose-limbed verse, Whitman is saying, This is who we are. All of us. This is who

I

am. That could be me.

I

am. That could be me.

I can’t say when I stopped posing hypotheticals on behalf of my father. But at some point I began to understand a number of different things at once. I understood that not one of my hypotheticals could have helped my father feel better about himself at his core. Not

Leaves of Grass

. Not a walk-up in the Village or an apartment in the Castro. I could not restore to my father something he’d never had. My father was molested before he could read or write. He needed more help than a book or any liberal, progressive locale could provide. He needed a different father.

Leaves of Grass

. Not a walk-up in the Village or an apartment in the Castro. I could not restore to my father something he’d never had. My father was molested before he could read or write. He needed more help than a book or any liberal, progressive locale could provide. He needed a different father.

I understood also that every one of my better-case scenarios inexorably lead to the same end: if my father had been truly different in the ways I was imagining, he would not have married my mother, he would not have become my father, and I would not exist. I would not have grown up to marry Christine and be a father to my sons. This is basic, obvious. Science Fiction 101. Mess with the chain of causality and everything changes. My life

depended

on my father’s shame and denial and secret life. My life, and the lives of my sons,

depended

on thousands of years of bigotry and hate-filled fear-mongering that was only now, in our lifetimes, beginning to change. When my father was leaving adolescence and entering adulthood, in the late fifties, Ellen did not have her own show. There were no openly gay cowboys on

Bonanza

, not even clichéd, limp-wristed, flamboyant ones. We were alive, my sons and I, because my father looked at his future and all its possibilities, and thought: Here is a path to happiness.

Marriage. Fatherhood. If only I can just not… If only I can just be …

depended

on my father’s shame and denial and secret life. My life, and the lives of my sons,

depended

on thousands of years of bigotry and hate-filled fear-mongering that was only now, in our lifetimes, beginning to change. When my father was leaving adolescence and entering adulthood, in the late fifties, Ellen did not have her own show. There were no openly gay cowboys on

Bonanza

, not even clichéd, limp-wristed, flamboyant ones. We were alive, my sons and I, because my father looked at his future and all its possibilities, and thought: Here is a path to happiness.

Marriage. Fatherhood. If only I can just not… If only I can just be …

I didn’t want a different father. I wanted to find a way to love my father the way I had always loved him. But that was no longer possible. I would have to find new ways to love him, to go along with the old ways that remained.

Subject: CDs & ArticleDate: Tue, 21 Oct 2008Hi Greg,I received your package and the article. Thank you so much. I have played two of the CDs so far and really love them. I will load up to five in my car and be able to listen to them when going places, like next weekend on my trip to Long Beach and the Halloween party at Anthony’s. I have been looking forward to receiving them and have been really pleased with what I’ve heard so far. I will enjoy them a lot for a long time…I have been getting out in the evening a little more of late. There are a couple of local bars where gay people congregate and both have Karaoke nights on Mondays and Wednesdays. I really enjoy singing along while others take the stage. I’ve even sang a few songs myself. However, most of the other singers do more recent stuff, and I have a tendency to stick to the material I know, like folk music. Please don’t worry that I am drinking too much. I don’t. I usually have one drink then move to soft drinks or water. I know there is still a possibility of becoming an alcoholic since my dad was. There is also the fact that alcoholics have a tendency to become diabetics and I surely want to avoid that. Besides, that’s just not me.I’ve been working a little more lately. It looks like the business is picking up on a steady basis. My boss is almost ready to expand to Seattle. He will go there and I will stay here in Spokane. We have already expanded into Coeur d’Alene and making plans to expand down toward the Tri Cities. This is something I could do for many years.I love you all very much. Thanks again for the CDs and the magazine.Dad

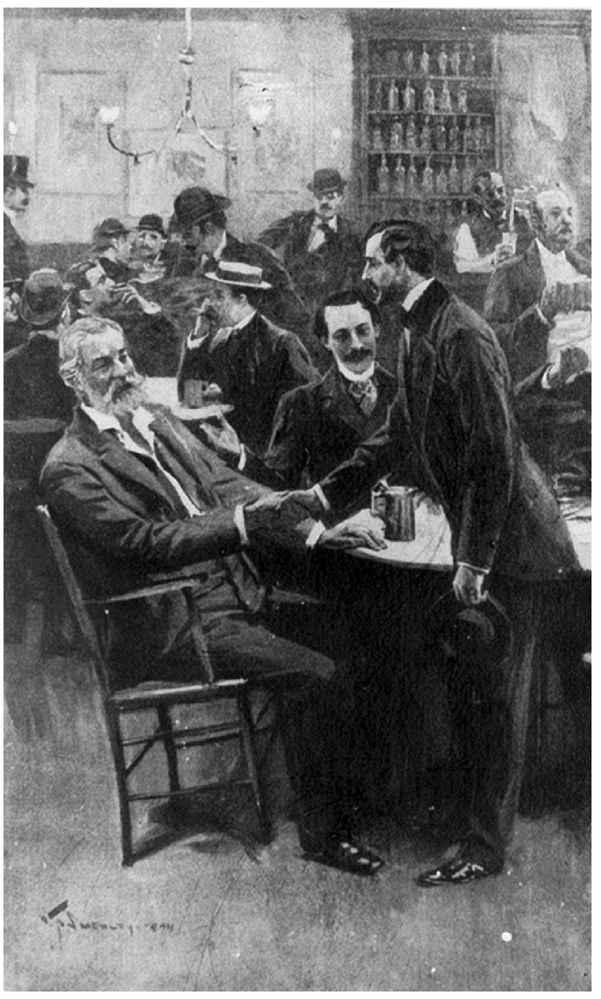

Walt Whitman (seated, collar open, shirt unbuttoned at the neck, chair back on two legs) at Pfaff ’s, a bar where gay people congregate in lower Manhattan. 1857.

My Father Contains Multitudes

THE PSYCHOLOGIST PAUL BLOOM DOESN’T SUBSCRIBE to the traditional view of the self, in which “a single, long-term-planning self – a you – battles against passions, compulsions, impulses, and addictions.” He offers instead a model of the first person plural:

The idea is that instead, within each brain, different selves are continually popping in and out of existence. They have different desires, and they fight for control – bargaining with, deceiving, and plotting against one another … struggles over happiness involve clashes between distinct internal selves … Some members are best thought of as small-minded children – and we don’t give 6-year-olds the right to vote. Just as in society, the adults within us have the right – indeed, the obligation – to rein in the children. In fact, talk of “children” versus “adults” within an individual isn’t only a metaphor; one reason to favor the longer-term self is that it really is older and more experienced. We typically spend more of our lives not wanting to snort coke, smoke, or overeat than we spend wanting to do these things; this means that the long-term self has more time to reflect. It is less selfish; it talks to other people, reads books, and so on. And it tries to control the short-term selves. It joins Alcoholics Anonymous … and sees the therapist … The long-term, sober self is the adult.

Other books

Broken Desires by Azure Boone

Black Dog by Caitlin Kittredge

The Truth in Lies (The Truth in Lies Saga) by McDonald, Jeanne

Trapped by Rose Francis

Haven Of Obedience by Marina Anderson

Don't Go Chasing Waterfalls by Elliott James

Darkest Highlander by Donna Grant

Dimitri by Rivera, Roxie

Prophecy (2011) by S J Parris

The Assassins' Gate by George Packer