Stories in Stone (12 page)

Authors: David B. Williams

D

EEP

T

IME

IN

M

INNESOTA—

M

INNESOTA

G

NEISS

These masses bear very evident signs of a crystalline origin,

but the process must have been a confused one.

—William Keating,

Narrative of an expedition to the source of

St.

Peter’s River, Lake Winnepeek, Lake of the

Woods, &c.

performed in the Year

1823

N

O MATTER WHERE you look at rocks, you are missing most of the story.

Either erosion has removed layers, no layers were deposited

in the first place, or the layers lay underground and cannot be seen.

If you live in a city, the geologic story may barely

equal a paragraph of time.

For example, in Seattle, where I live, the oldest rocks you can see are the 55-million-year-old

basalts of the Olympic Mountains.

The skyline-defining volcanoes, such as Mt.

Rainier to the south and Mt.

Baker to the north,

are each under a million years in age, and the last glaciers, which carved the modern topography, retreated only thirteen

thousand years ago.

Going to a wilder locale may add only a few chapters to the story.

In Moab, Utah, my home for nine years, you can pick up

salt that had crystallized out of a sea 300 million years ago, climb a mountain that solidified as a hot hump of magma between

sheets of sandstone 24 million years ago, or canoe between canyon walls carved by a river 2 million years ago.

The story has

expanded to a third of a billion years long, but many small gaps exist and no evidence occurs for the first 4 billion years

of Earth’s history.

Even the Grand Canyon, where you can see a mile of rock, fails to convey a complete story.

The oldest layer, the Vishnu Schist,

dates only to 2 billion years, and the youngest, Kaibab Formation, settled in a sea 245 million years ago.

There is a known

gap in the geologic record between 1.4 billion and 600 million years ago, as well as several slimmer pieces of missing time.

I am not bothered by this.

It is a fact of life.

Geologists have terms for such gaps of time.

“Unconformity.” “Disconformity.” “Nonconformity.” Each refers to a specific missing

element.

An unconformity is the most generic and refers to any break in the rock record.

Again, either something was not deposited

or something was removed.

If that gap occurs between two layers of rock that are parallel, it is called a disconformity.

A

nonconformity refers to contact between two very different rock types, sort of like the relationship between a NASCAR mom

and an NPR dad.

An angular unconformity describes two rock units where there is an angle between the two layers.

One of the most famous of these unconformities is at Siccar Point, about thirty miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland.

1

There on a sunny June day in 1788, James Hutton sailed along the Berwickshire coast with his friends John Playfair, who later

became Hutton’s biographer, and Sir James Hall, who owned the boat.

Three years earlier, at a presentation to the renowned

Royal Society of Edinburgh,Hutton, an eccentric farmer and naturalist, had proposed that Earth was so old that no one could

make a good estimate as to its age.

Few had accepted Hutton’s radical idea and the three men, or at least Hutton, were seeking

evidence to prove his theory of an ancient Earth.

They began their trip on Hall’s property at Dunglass Burn and proceeded east and south along the jagged coast, rounding several

headlands before arriving at Siccar Point, where they found two rock layers.

The lower strata consisted of gray beds of silt

and sand, which stood on end like upright fingers of a hand.

Resting directly atop the fingers were horizontal beds of red

sandstone, which those in the eastern United States would call a brownstone.

From what we know about this adventure, Hutton gleefully explained to his friends that the gray stone, which he called schistus

and which modern geologists call graywacke, had formed in the sea over vast epochs of time.

Subsequent to its conversion to

rock, the gray beds had been tilted vertically, and finally uplifted above the sea.

More time passed, the sea rose, and sediments

washed out of the nearby mountains and covered the schistus.

Finally, Hutton told his fellow seekers of time that the gray

and the red must have risen again, together as one.

Clearly great ages of time had passed in order to generate such an unlikely

wedding of rock.

Our three Scotsmen had no way of knowing how much time had passed between the schistus and the sandstone,

but the beds at Siccar dramatically illustrated that Earth was far, far older than previously thought.

Geologists are still finding these gaps.

In contrast to when Hutton found Siccar Point and could only recognize a relative

gap, modern geologists can determine the absolute gap.

They can take almost any rock, crush it to a powder, probe its chemical

constituents on a microscopic level, and determine its age, whether in the thousands, millions, or billions of years.

Using these techniques, known as radiometric dating, geologists have discovered that a stone in the building trade has one

of the longest story lines of any rock on the planet.

The geologic tale of the Morton Gneiss (pronounced “nice”), quarried

in Morton, Minnesota, stretches from its origin 3.5 billion years ago to 12,900 years ago.

In that time the swirly pink, gray,

and black, heavily metamorphosed Morton rocks were buried, baked, squeezed,warped, uplifted, injected with magma, and stripped

bare by massive rivers.

This 3.5-billion-year-long adventure created what one geologist calls “the most beautiful building

stone in the country.”

2

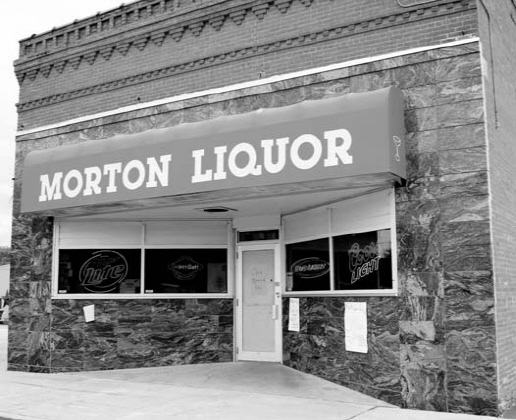

My favorite Morton-covered building stands at the southeast corner of the main intersection in Morton, where State Route 19

crosses Main Street.

It is architecture at its most utilitarian—rectangular, two stories tall, and brick.

The builder did,

however, incorporate some semblance of an aesthetic with the cornice and frieze, which have a pattern of outlined squares

atop two horizontal rows of raised bricks resting on another row of inverted, stepped pyramids.

A faded red awning adds another touch of character, boldly proclaiming in large white letters, MORTON LIQUOR.

Neon signs in

the window hawk several brands of lite beers.

Perhaps the store’s owner thinks that Mortonians, or at least those who drink,

should be concerned about their weight.

Below the cornice, polished slabs of Morton Gneiss cover the front of the building.

Pink and black layers corkscrew around

each other as if they are still fluid.

Other layers look stretched and torn like taffy.

Four-inch-wide eyes of black minerals,

complete with white eyebrows, dot the variegated layers.

This complex texture of light and dark bands typifies gneiss, a type

of metamorphic rock formed from great heat and pressure.

Located two hours west of Minneapolis along the Minnesota River, Morton showcases a full complement of uses for its eponymous

gneiss.

The old high school features Morton blocks for accents, window lintels, and entryways.

A few blocks away, the Zion

Evangelical Lutheran Church, Wisconsin Synod, is made entirely of rounded, rough cut Morton stones, and the curbs on Main

Street must be the most colorful as well as the oldest ones in the world at 3.5 billion years.

In the cemetery above town,

numerous headstones are made from Morton Gneiss.

(Cemeteries are one of the best places to find the psychedelic rock; I have

seen Morton headstones around the country.)

Morton Liquor in Morton, Minnesota.

The first person to note the building potential of the Morton stone was Giacomo Constantino Beltrami.

A former Italian soldier,

he was a political exile who hoped to make a name for himself in America by finding the source of the Mississippi River.

In

June 1823 Beltrami had joined Major Stephen Long’s expedition up the Minnesota River, then called the St.

Peter’s River and

thought to be a possible source of the Mississippi.

Beltrami wrote in his 1828 travel narrative that tears filled his eyes

when he first saw the rock along the Minnesota River.

“I should have given myself up to its sweet influence had I not been

with people who had no idea of stopping for anything but a broken saddle.”

3

When he emerged out his reverie he noted that the “immense blocks of granite scattered here and there with such a picturesque

negligence, might with small aid from the chisel be raised to rival the pyramids of Memphis or Palmyra.”

4

In lieu of grandiose structures, added Beltrami, the magnificent stone could easily be worked and fitted for barns, temples,

or, for any local royalty, palaces.

Sixty-one years would pass before quarrying would begin in Morton, when Thomas Saulpaugh opened a quarry on a high dome of

rock just west of town.

By 1886 three hundred men worked the property.

Other quarries opened on the southeast edge of town,

along the railroad tracks, and by 1935 five companies operated holes, the biggest of which was owned by Cold Spring Granite

Company.

To move the stone, which quarrymen cut into Volkswagen bus–sized blocks weighing between fifty and eighty tons, Cold

Spring built what was reportedly the largest swing boom in the world.

5

The steel mast rose 120 feet and supported a boom that could reach out 100 feet.

Thirteen cables as thick as a man’s wrist

held the derrick in place, enabling quarrymen to move with ease blocks weighing up to a hundred tons.

Quarries sold the colorful stone under trade names such as Oriental, Tapestry,Variegated, and Rainbow granite.

In what seems

a rather ignoble fate, Cold Spring also sold crushed Morton as grit to go into turkey feed.

At least the turkeys returned

the Morton to the earth.

Records do not exist as to how much of it got shipped around the country or where it went, but some beautiful Morton buildings

went up in the 1920s and 1930s.

None were pyramids or palaces.

The buildings include the tallest structure in Brooklyn, New

York, the 512-foot-high Williamsburgh Savings Bank; the first modern planetarium in the western hemisphere, the twelve-sided

Adler Planetarium in Chicago; and numerous structures now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including Tulsa’s

Oklahoma Natural Gas building, Richmond,Virginia’s, Old State Library, and Cincinnati’s Cincinnati and Suburban Bell Telephone

Company building.

Most of these buildings share two features.

The first is that builders used the gneiss only at the ground level, because the

Minnesota rock cost more but better resists urban agents of erosion, such as road salt, soot, and noxious vehicle emissions,

than limestone and sandstone does.

Second, the buildings were designed in the art deco, or moderne, style.

The best Minnesota

example is the Northwestern Bell Telephone Building in Minneapolis.

Now owned by Qwest and formerly by AT&T, the twenty-six-story

tower was built between 1930 and 1932.

The main entry of Morton Gneiss consists of three square recessed arches topped by a keystone shaped like a stylized bird

reminiscent of Egyptian art.

Running along the top of the polished gneiss panels are classic moderne-style chevrons and zigzags

against a background of vertical bands.

Adjacent to the monumental entry rise geometric designs that resemble a tree with

outstretched limbs dangling inverted triangles.

A caduceuslike motif with lightning bolts replacing the traditional snakes

surmounts each of the trees.

Two adjacent doorways, each topped with another Egyptian-style bird, lead into a side entrance.

Kasota limestone from southern Minnesota covers the remaining twenty-five stories.

Morton Gneiss was an ideal stone for art deco projects.

It fit the style’s aesthetic for unusual colors, particularly as a

counterpoint to the light-colored, monochromatic stone often used above the base.

(By highlighting the dark/light contrast,

builders created their own unconformity.

In the case of the Morton-Kasota contact, the missing time gap covering 3 billion

years was what geologists call a “great unconformity.”) Dark gneiss helped distinguish a building and set off the base from

the surrounding structures.

The Morton’s swirled surface also provided a natural counterpoint to the era’s prevailing fascination

with machines and geometric patterns, as well as a complement to the fashion for abstract organic forms.