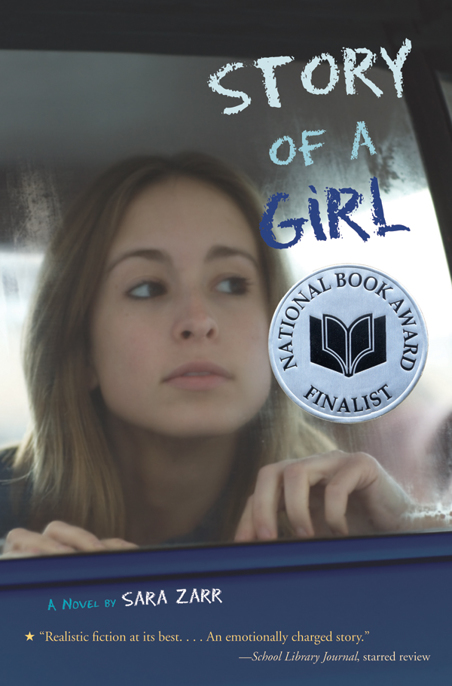

Story of a Girl

A Preview of

The Lucy Variations

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For everyone who is my family.

First Lesson

Lie back, daughter, let your head

be tipped back in the cup of my hand.

Gently, and I will hold you. Spread

your arms wide, lie out on the stream

and look high at the gulls. A dead-

man’s float is face down. You will dive

and swim soon enough where this tidewater

ebbs to the sea. Daughter, believe

me, when you tire on the long thrash

to your island, lie up, and survive.

As you float now, where I held you

and let go, remember when fear

cramps your heart what I told you:

lie gently and wide to the light-year

stars, lie back, and the sea will hold you.

— Philip Booth

I was thirteen when my dad caught me with Tommy Webber in the back of Tommy’s Buick, parked next to the old Chart House down in Montara at eleven o’clock on a Tuesday night. Tommy was seventeen and the supposed friend of my brother, Darren.

I didn’t love him.

I’m not sure I even liked him.

The car was cold and Tommy was stoned and we’d been there doing pretty much the same thing a dozen times before, and I could smell the salt air from the beach, and in my head I wrote the story of a girl who surfed the cold green ocean, when one day she started paddling in the wrong direction and didn’t know it until she looked back and couldn’t see the shore.

In my head I wrote the story, while Tommy did his thing, one hand wrapped around my ponytail.

It was the girl — the surfer girl — I had on my mind when Tommy swore and got off of me. My dad dragged him out of the car, then me. He threw Tommy to the ground and pushed me into our old Tercel.

Right before we pulled out of the lot, I stole a look at my dad. There might have been tears slipping down his cheek, or it might have been a trick of the headlights bouncing off the night fog.

I started to say something. I don’t remember what.

“Don’t,” he said.

That was almost three years ago.

My dad hasn’t looked me in the eye or talked to me, really talked to me, since.

They made us clean out our lockers on the last day of sophomore year. I tore down the class schedule I’d taped to the inside of the door at the beginning of the semester and tossed it into the pile of recycling that already included ninety-five percent of the crap I’d busted my ass to do all year. What was the point of all that so-called learning if, in the end, it was going into the trash? The only stuff I kept was from Honors English. I would deny this if asked, but I thought I might want to read some of my essays again. There’s this one from when we read

Lord of the Flies

. I really got into it, the savagery and survival-of-the-fittest stuff. A lot of kids in my class didn’t get it. Jeremy Walker asked, “Why couldn’t the boys on the island just get along?”

Then Caitlin Spinelli was all, “Yeah, didn’t they know their chances for survival were, like, so much better if they worked together?”

Hello! Walk down the halls of your own school for three seconds, Spinelli: we

are

savages. There is no putting of the heads together to come up with a better way. There is no sharing of the bounty of popularity with those less fortunate. There is no pulling along of the deadweight so that we can all make it to the finish line. At least not for me. Caitlin Spinelli might have a different perspective, being rich in all the things that would have put her in the surviving tribe.

Anyway, Mr. North wrote on my essay in purple pen. He used red pen to correct spelling errors and messed-up grammar and stuff like that, but when he just wanted to let you know he liked something, he used purple.

Deanna,

he wrote,

you clearly have much of importance to say.

Much of importance.

“Yo, Lambert!”

Speaking of savages, Bruce Cowell and his pack of jock-wannabes, who’d been kicked off every school team because of attitude problems and/or the use of illegal substances, were right on schedule for their weekly feats of dumbassery.

Bruce leaned up against the lockers. “You look hot today, Lambert.”

“Yeah.” Tucker Bradford, flabby and red faced, came close and said, “I think your boobs got bigger this year.”

I kept sorting through the stuff in my locker, peeling a piece of candy cane left from Christmas off one of my binders. I reminded myself it was the last day of school, and besides, those guys were seniors. If I could get through the next five minutes I would never have to see them again.

However, five minutes is a long time, and sometimes I just can’t keep my mouth shut.

“Maybe,” I said, pointing at Tucker’s chest. “But they’re still not as big as yours.”

Bruce and the lackeys watching from a few feet away laughed; Tucker got redder, if that was possible. He leaned in with his nasty Gatorade breath and said, “I don’t know what you’re saving yourself for, Lambert.”

This is the thing: Pacifica is a stupid small town with only one real high school, where everyone knows everyone else’s business and the rumors never stop until some other kid is dumb enough to do something that makes a better story. But my story had the honor of holding the top spot for over two years running. I mean, a senior getting caught with his pants down on top of an eighth-grade girl, by the girl’s

father

(“No way! Her

father

? I’d just kill myself!”) was pretty hard to beat. That story had been told in hallways and locker rooms and parties and the back of classrooms since Tommy first came to school the morning after it happened. At which time he gave all the details to his friends, even though he knew it meant my brother, Darren, would kick his ass. (He did.) By the time I got to Terra Nova for ninth grade, the whole school already thought they knew everything there was to know about Deanna Lambert. Every time someone in school saw my face, I knew they were thinking about it. I knew this because every time I looked in the mirror, I thought about it, too.

So when Tucker breathed his stink all over me and said what he did, I knew it meant more than just a generic insult suitable for any girl. He reduced my whole life story into one nine-word attack. For that, I had to send him off in style. I started with the middle finger (you really can’t go wrong with a classic). I followed it with a few choice words about his mother, and finished by implying that maybe he wasn’t into girls.

Right about then I wondered if there were any teachers or otherwise responsible adults around in case Tucker and Bruce and their friends decided to take it beyond words. Probably I should have thought of that sooner.

Bruce chimed in. “Why do you front, Lambert? Why pretend you’re not a skank when you know you are?” He gestured to himself and the guys around him, “

We

know you are.

You

know you are. And, um, your

Dad

knows you are, so . . .”

A voice called from down the hall: “Don’t you guys have some kittens to go torture or something?”

Jason had never sounded so good.

“You don’t

even

want a piece of this, punk,” Tucker said, shouting over his shoulder.

Jason kept walking toward us, with his usual no-hurry slouch, black boots scuffing along the floor like it was just too much effort to pick up his feet. My hero. My best friend.

“Didn’t you, like,

graduate

yesterday?” he said to the guys. “Isn’t it a little pathetic to still be hanging around here?”

Bruce grabbed Jason’s jeans jacket and slammed him up against the lockers. Where in the hell were the people in charge? Had all the teachers fled for the Bahamas as soon as the last bell rang?

“Get off him,” I said.

One of Tucker’s friends said, “Come on, man, we don’t have time for this shit. We promised Max we’d have the keg there by four.”

“Yeah,” said Tucker, “my brother only works at Fast Mart for like ten more minutes. After that, we’re gonna get carded.”

Bruce let go of Jason and gave me one last look, straight into my eyes. “See what a waste of time you are, Lambert?”

We watched them go down the hall and disappear around the corner. I kicked my pile of recycling and watched the papers fly.

“You okay?” Jason asked.

I nodded. I was always okay. “I have to drop off my French book, then sophomore year is officially over.”

“About time. What now?”

“Denny’s?”

“Let’s go.”

After Denny’s, we went to the CD store and mocked the music on the listening stations, then Jason tagged along while I picked up job applications from all the stores and food places at Beach Front, a sad, tired strip mall that hardly anyone shopped at since the second Target opened over in Colma. We didn’t talk much. I kept reliving Tucker’s breath on me as he said what everyone at school probably thought.

Jason and I are okay without talking. That’s how you know you really trust someone, I think; when you don’t have to talk all the time to make sure they still like you or prove that you have interesting stuff to say. I could spend all day with him and not say a word. I could look at his face all day, too. His mom is Japanese and his dad, who died right after Jason was born, was white. Jay has this amazingly shiny black hair and long eyelashes, with his dad’s blue eyes. (Why do guys always have eyelashes girls would kill for?) Frankly, I never understood why girls around here didn’t throw themselves at him. Maybe because he’s on the quiet side, and short, like his mom. Doesn’t bother me, because we’re almost the same height and would match up perfectly if there was ever any occasion for matching up.

He’s laid-back. He’s loyal. He gets it. In fact, the only thing wrong with Jason is that, at the time, he happened to be the boyfriend of my other best friend, Lee.

Unlike Jason, who’s known me forever, Lee only recently achieved best-friend status by transferring in from a school in San Francisco and being all cool. Not cool as in dressing right and knowing anything about music or whatever, but cool as in being the kind of person who doesn’t try to be someone she is not.

I met her in PE when she did a belly flop off the vault during our lame gymnastics unit. Mrs. Winch kept saying, “Walk it off, Lee, then do it again.” I was like, excuse me but I don’t think she’s breathing, and hell if

I’m

going to kill myself on that thing, too. We both got a zero for the day and a lecture from Mrs. Winch about our lack of “gumption.”

I watched her around school after that. She’s slightly on the dorky side, with this short hair that never does anything right and clothes that fall just on the wrong end of trying too hard. I figured the slightly-on-the-dorky-side group at school would take her in pretty quick — you know, the drama geeks and college entrance club people — but I watched her for a while and she didn’t have anyone. Which meant she probably hadn’t gotten connected enough to know about me yet. So I started talking to her and got a feeling, like she was different from most of the other girls who only cared about how they looked and were always talking smack about their supposed best friends.

Once we started hanging out, she told me that her real dad’s a drunk and she didn’t know where he was, and I told her that’s okay, my dad hates me. When she asked why, I told her about Tommy. It felt good to be able to tell

my

version instead of Tommy’s, the one that everyone at school knew. After I told her, I got worried she wouldn’t like me anymore or she’d start acting weird around me, but she just said, “Well, everyone has stuff they wish they could change, right?”

So I guess it’s my own fault Jason hooked up with her. I kept talking about Lee this and Lee that and Jay you should get to know Lee; you’d like her. He did.

I didn’t care, really. Everyone knows that if you start fooling around with your friends, you can kiss what’s best about your friendship good-bye. I tried to see it like I had the better end of the deal, that if Lee and Jason broke up, they probably wouldn’t hang out anymore, whereas I would still get to be his friend.

Once in a while, though, something little would happen, like they’d be walking down the hall at school holding hands and I’d see them but they wouldn’t see me, and first I’d think, God are they cute together! And then it felt like I was watching something superprivate, something that he had only with her. I always thought I knew him better than anyone, but once they started going out it was like Lee was some kind of insider in a way that I wasn’t.

Jason and I still had our days, like the last day of school, when it was just us, and even though it sounds semidisloyal to say this, times like that I pretended Lee didn’t exist.

Until he’d start talking about her.

“. . . I got a text from Lee during fourth,” he was saying. Our bus wound its way down Crespi Drive and into the flats, where we both lived. “They were on the beach in San Luis Obispo.”

She and her family had left that morning for Santa Barbara, to pick up her brother from college. “When’s she coming back?”

“Day after tomorrow. Her stepdad has to get back to work.”

“Right.”

The bus heaved to a halt at my stop, the stop I’d been getting off at my whole life, in front of a mold-gray house a few doors down from ours, with five cars parked on the lawn — cars that had been there since the dawn of time, at least.

“Call me tomorrow,” Jason said.

“Yeah.”

It was the worst part of every day, when the bus got to my stop and I had to leave Jason, him still rolling, still on his way to something, while I’d reached the daily dead end known as my house.

I stood outside the front door for my usual count of ten before walking inside. One, two . . . don’t notice how the garage door doesn’t hang straight . . . three, four, five . . . forget about the broken flowerpot that’s been in a heap on the lawn since last summer . . . six, seven . . . it’s okay, everyone leaves their Christmas lights up all year . . . eight . . . the front porch is a fine place for a collection of soggy cardboard boxes . . . nine . . . oh, forget it, just turn the knob and go in already.

Ten is everything else: the smell of mildew that never goes away, the five steps over green shag to go from the living room to the kitchen, the Pepto-pink walls of the kitchen, and, finally, my parents.

“You’re home late.” Dad, compact and self-contained, an island on a kitchen chair, didn’t look up from his dinner when he said it. “Better get started on your homework.”

“It was the last day of school, Dad.”

His fork paused for a second, then he kept eating. “I know. I’m just saying that I hope you plan to stay out of trouble this summer.” As if I’d been in all kinds of trouble, which I hadn’t, not for a long time. “Did you hear what I said?”

“Yeah.”

Mom’s cheery voice chimed in the way it always does when she sees a subject that needs changing. “Why don’t you sit down and have some dinner with us?”

“I ate.”

“Well, then, dessert,” she said, heaping more food onto Dad’s plate, her dyed and fried hair falling over her face. “How about some ice cream?”

Mom’s favorite phrases are:

1.

Your father just isn’t very expressive. (

Interchangeable with

Just because he doesn’t say he loves you doesn’t mean he doesn’t feel it.)

2.

We simply need to put it behind us; be a good girl and it will be all right.

3.

How about some ice cream?

“Is Darren home from work yet?” I asked.

“Stacy just left for work and to drop off the car,” Mom said. “Or pick up the car. I can never remember how it works.”

Darren still lived at home, which wasn’t exactly the plan — not for him, not for my parents. When his girlfriend, Stacy, got pregnant and decided to keep the baby, their only option was to move into our basement and give up on anything resembling a plan.

He and Stacy both worked at Safeway — Darren days and Stacy nights — so that one of them could always be with the baby, April. Which was a good system, I guess, except that they never saw each other unless they were handing off the keys to their one car.

“Stacy got out of here late, as usual,” Dad said. “She’s lucky they don’t fire her.”

“She’s made employee of the month twice,” I reminded him as Mom handed me a bowl of fudge brownie ice cream that I hadn’t asked for.