Strip Search (16 page)

Authors: William Bernhardt

Tags: #Police psychologists, #Serial murders, #Mystery & Detective, #Ex-police officers, #General, #Patients, #Autism, #Mystery fiction, #Savants (Savant syndrome), #Numerology, #Suspense, #Fiction, #Autism - Patients, #Las Vegas (Nev.)

“Well,” I answered, “Colin tells me you’re an expert in…I’m sorry, I don’t know how else to put it. Weird math.”

I was relieved to see she didn’t take offense. In fact, she laughed. “In the scholarly world, we call it cryptomathematics. It’s a discipline that combines elements of mathematics and philosophy. We apply the fundamentals of mathematics not simply for the more common ontological purposes but to pursue teleological inquiries as well.” She must’ve noticed the blank expression on my face, because she added: “We apply math not simply as a way of solving problems but of understanding the mysteries of the world in which we live.”

I nodded as if I understood; I was processing information much more slowly than usual. I tried to shake myself out of the cloud and force myself to function. “Well, I suppose that beats doing calculus.”

“Funny you should say that. Differential calculus was invented by Isaac Newton, you know.”

“May he burn in hell.”

“He was a seriously strange dude, not at all the Sunday school genius you learn about in science class, sitting around waiting for an apple to fall on him so he could invent gravity, a story he probably made up.”

“You’re joking.”

“I’m not. I did my dissertation on Newton. Sure, he experimented with gravity and light prisms and optics and higher mathematics, but as it turns out, he spent far more of his time dabbling in alchemy.”

“You mean, trying to turn lead into gold?”

“Exactly.”

“But isn’t that…totally cracked?”

“That would be a nice way of putting it. Worse, in his day, it was illegal and perceived as anti-Christian, so he did all his alchemical work in secret. Most scholars today believe his thoughts on gravity arose from those alchemical experiments—although he couldn’t admit it—not any apple-falling epiphany. For that matter, he also dabbled in sorcery and astrology and biblical prophecy; he had this whole timeline worked out of not only the history of the universe but the future. All the way from Adam and Eve—which by the way only occurred about six thousand years ago—right up to judgment day.”

I gulped. “Dare I ask?”

“You can relax. According to Newton, the Second Coming is scheduled for 2060.”

“Yikes.”

“Yeah. He believed it, even though he never published it in his own lifetime. At the end of his life, Newton compared himself to Christ; he believed he was the only person able to interpret this divine knowledge. He wrote far more about the Bible than he did math; his future history analysis is ten times as long as the

Principia Mathematica.

”

“And this is the world’s greatest mathematician? Sounds more like the profile of a serial killer.”

“You’re not far wrong. He was neurotic, suicidal, anti-Semitic.” She took a deep breath. “And then in his spare time, he revolutionized the world. He built the best refracting telescope. He made the Industrial Revolution possible.”

“Even though he was wicked whacked.”

She smiled. “Even though.”

“And you chose to do a paper on this guy?”

She shrugged. “Hey, I got my Ph.D. You gotta do something to get academia’s attention. It made a good dissertation, even if the man was mad. Ingenious, but mad. A dangerous combination.”

Yes, that much was becoming clear to me. And I very much suspected that combination had made its way to beautiful downtown Vegas.

“I’M TELLING YOU, Chief, her speech was slurred.”

“I don’t believe it.”

“Why would I lie?”

O’Bannon looked up at Granger, one eyebrow cocked.

Granger pressed his fists against O’Bannon’s desk. “Look, I’ll admit that Pulaski and I have had our differences. But we’ve also worked together—remember?”

“I just talked to the woman this morning. And she wasn’t drunk.”

“She could’ve been faking it. You can’t be sure.”

He looked at his detective with a steely eye. “I’ve been on the police force for thirty-four years,” he said levelly. “I can be sure.”

“Then maybe she stopped off someplace on her way to the office. I don’t know. All I can tell you is, when she came in here, she wasn’t right. She was too loose, too…I don’t know. Un-Susan-like. Calmer. Relaxed. And she was definitely slurring her words.”

“Personally, I think a calmer, more relaxed Susan might be a pleasant change of pace.”

“Assuming she’s sober. But she wasn’t.”

“She’s been clean for months. Why would she start drinking now?”

“Because for the first time in months, you’re actually asking her to do something!”

O’Bannon didn’t respond.

“You think I don’t know you’ve been going easy on her, making sure she didn’t encounter anything that might put her under stress? Everyone in the department knows!”

“So you’re saying you want me to hire a different behaviorist? Take on a second expert consultant?”

Granger paused. “I’d rather scratch the psycho-profilers and redirect that money to manpower. Let me beef up my detective squad. Hell, we’ve got a description on the guy. We just need to fan out, hit the streets, track him down.”

O’Bannon pushed away from his desk. “Look, you want extra manpower, fill out the forms and I’ll see if I can get it. I’ll back you one hundred percent. It’s not an either/or deal.”

“You know as well as I do how strapped the budget is in this crappy economy. No way the city council will let me increase spending unless I can show them where I’m going to get the money.”

O’Bannon didn’t bother arguing with him. “Nonetheless, as long as the perp remains at large, it would be irresponsible to fire our best psy—”

Granger slapped a newspaper on O’Bannon’s desk. “Have you read this yet?”

He unfolded the morning edition of the

Courier

and glanced at the under-the-fold headline. FACE KILLER STILL AT LARGE, and beneath that, POLICE BAFFLED. The article was by Jonathan Wooley, one of the top crime reporters for the paper, one O’Bannon knew all too well. He skimmed the article quickly. Wooley was unstinting in his criticism of the police department. Even though they hadn’t released all of the gruesome details of the case, Wooley was still basically telling his readers they weren’t safe on the streets.

“Prepare a statement. Tell them as little as you can. Pretend we’re following up on a lot of serious leads.”

Granger paced back and forth, his frustration mounting. “You know what I think? I think you know how risky Susan is. I think you know she’ll start drinking again, sooner or later. You’re just protecting her because you used to be her father’s partner!”

“And you know what I think?” O’Bannon replied, matching his volume. “I think you’re still pissed because of what happened to her husband—

your

partner—even though you don’t know a damn thing about it.”

“That’s such bull—”

“Or maybe it’s because she didn’t melt in your mouth when you came on to her the first day you transferred over here. Which is it?”

Granger’s face crinkled with rage. “I am just trying to help you! All I want is what’s best for the department!”

“Then get out of my office and solve this case!” O’Bannon shouted.

Granger slammed the door on his way out.

O’Bannon fell back in his chair, exhausted. He pressed his fingers against his forehead, trying to fight off an incipient migraine.

Of course, Granger was right, at least about many things. He was protecting Susan. He couldn’t forget her father—or what happened to him. For that matter, he’d known Susan all her life; he couldn’t stand by and let her go down the tubes without trying to stop it.

Was she really slurring? He hadn’t noticed it this morning on the phone. But as much as Granger might hate her, he couldn’t imagine that the man would just make it up. If she was drinking again, Granger wouldn’t be the only one who noticed, no matter how practiced she was at hiding it. Her career as a police officer would be finished. He would’ve let her down. Again. He would’ve dishonored the memory of her father, who—even though no one knew it but him—gave his life for O’Bannon’s.

And Darcy would never forgive him.

He closed his eyes and said a silent prayer, something he had gotten more used to doing during the months of recovery and rehabilitation following his gunshot wound.

Please God, whatever it is she’s doing—tell her to stop. Tell her to stop now, before it’s too late.

He tried to return his attention to the two dozen other files on his desk, but he couldn’t really focus; he might as well have been reading James Joyce for all he comprehended of it. His mind was on Susan.

Please, Susan, be smart. Just this one time.

Be smart

!

“I’VE READ about the murders in the paper,” Dr. Goldstein said. “Horrible. But what do they have to do with my field of study?”

I handed her a photocopy. “This was found scrawled in grease at the scene of the first murder. It appears to be a mathematical equation, although by all accounts, an impossible one. Does it mean anything to you?”

She had looked at it for barely two seconds before a broad smile crossed her face. “Oh, yes. That again.”

“That—what?” I craned my neck. “Have you seen this before?”

“Of course. Many times.”

“But—what is it?”

She laughed, then passed it back to me. “It’s a joke.”

“A joke? What do you mean?”

She settled back in her chair. “You’ve heard of the Swiss mathematician Euler?”

To hedge or not to hedge…“The, uh, name sounds familiar…”

“He was a major figure in the history of mathematics. Is credited with being the first person to apply calculus to physics. Was the first to use the term

function

in a mathematical context.”

“And this equation has to do with his work?”

“No, this has to do with his joke. As the story goes—and I warn you, it may be entirely apocryphal—Euler was a guest in the court of Catherine the Great at the same time as the great philosopher Diderot. Diderot was an atheist—or to be more accurate, he refused to believe in anything that couldn’t be proven by rational, logical, or deductive principles. Anyway, he was making a big scene in court, offending everyone, declaring loudly that, ‘I will believe in God when you prove to me that He exists.’ So Euler hands him this formula and says, ‘There.

hence God exists, reply!’” She laughed. “Q.E.D.”

I really wished Darcy had come in with me. It might’ve saved me so much embarrassment. “And…was he right?”

Dr. Goldstein gave me a long look. “Do you really think a mathematical formula could prove the existence of a divine maker? It was a joke. But Diderot didn’t know. So he takes the formula and mumbles something like, ‘Oh.’ And crawls back to his room and stays there for the rest of the week, not bothering anybody. Euler becomes the hero of the court.”

“Great story,” I said. “But a little obscure. Most serial killers aren’t, you know, students of little-known moments in the history of French philosophy.”

“Oh, this theory gets around more than you know. Your killer may read the Mathematical Games column in

Scientific American,

or books on famous practical jokes. Maybe he’s addicted to the History Channel.”

I nodded. “I’ve always been suspicious of people who are addicted to the History Channel.”

She laughed. “My point is, it wouldn’t take a mathematical genius to scrawl this formula. This equation may have been intended as a joke, but hey, all the world loves a joke. And as you said before, without more information, it is totally insoluble.”

“So when the killer left this behind at the scene of the crime, he was…” I held up my hands. I had no idea how to finish the sentence.

“I’m no detective,” Dr. Goldstein replied. “But my guess is he was doing the same thing to you that Euler was doing to Diderot. Pulling his leg.”

I nodded slowly. “Leading us on a wild goose chase. Proving how much smarter than us he is.” Which was a common trait of the narcissistic personality disorder. And much as I hated to admit it, it would fit well with Granger’s sexual obsessive theory, too. “And this has nothing to do with your work? That…crypto…thingie.”

“No. There have been some serious efforts to link theology and mathematics, but this isn’t one of them. Have you heard of Pythagoras?”

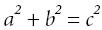

Darcy, of course, could’ve recited the entire encyclopedia entry on Pythagoras. I was stuck with: “Didn’t he have some kinda theorum or something?”

“Very good. You remember your high school geometry.” Was that a compliment? I wasn’t sure. “Pythagoras proved